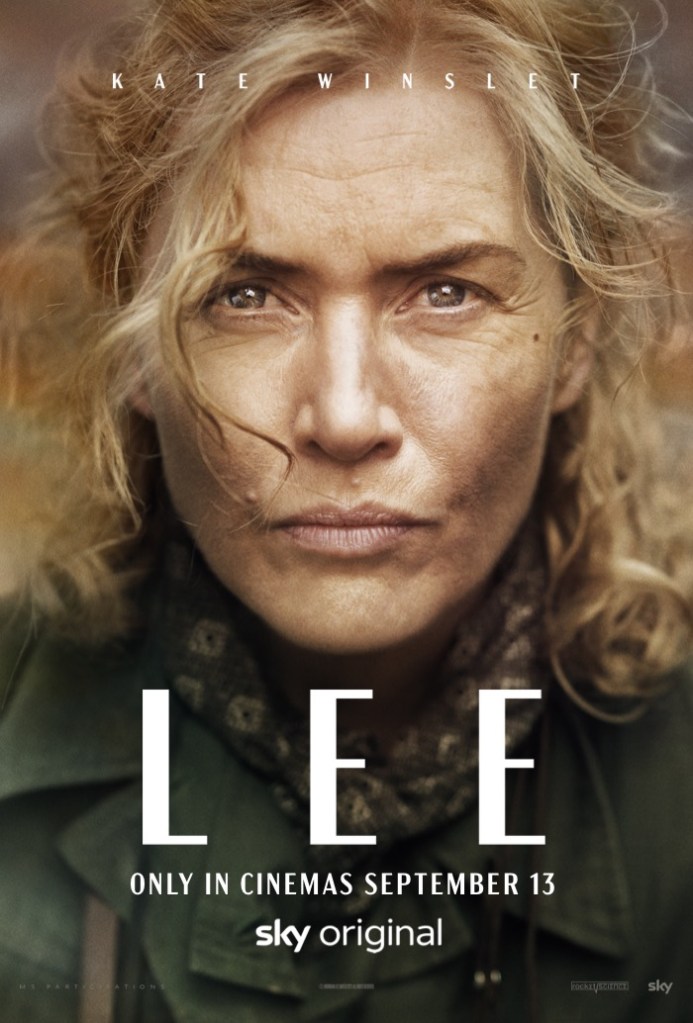

Kate Winslet plays with passion in an otherwise rather safe and traditional biopic

Director: Ellen Kuras

Cast: Kate Winslet (Lee Miller), Marion Cotillard (Solange d’Ayen), Andrea Riseborough (Audrey Withers), Andy Samberg (David Scherman), Noémie Merlant (Nusch Éluard), Josh O’Connor (Interviewer), Alexander Skarsgård (Roland Penrose), Arinzé Kene (Major Jonesy), Vincent Colombe (Paul Éluard), Patrick Mille (Jean D’Ayen), Samuel Barnett (Cecil Beaton), Zita Hanrot (Ady Fidelin)

“War? That’s no place for a woman!” That’s the message photographer Lee Miller (Kate Winslet) received when she applied to head to the Western Front for Vogue in World War Two. An experienced artist and photographer, with a strongly independent mindset, Miller wasn’t taking no for an answer: her stunning images of the horrors of war and the Holocaust would become a vital historical record.

That’s the key message of this well-meaning, rather earnest, slightly old-fashioned film, a callback to hagiographic biopics of yesteryear. It’s told through a framing device of an older Lee being interviewed in the 70s. The interviewer is played, in a thankless role, by Josh O’Connor (the character’s identity is a late act reveal that most viewers will probably guess early) and his dialogue is awash with either the sort of “and then you married and left France and moved back to London where you became the first woman photographer hired by Vogue” narration that links time-jumped scenes together, or blunt statements about Lee’s emotional state (“you must have been very frustrated”) that Winslet is definitely skilled enough to do with her face alone.

This was a passion project for Winslet, who spent a decade bringing it to the screen and which she bailed it out during a funding wobble, and she is the main reason to watch Lee. This strong-willed, take-no-nonsense bohemian turned hardened professional is a gift for Winslet, but she also gives Miller a strong streak of inner doubt and fear. Under her force-of-nature exterior, there is a strong streak of vulnerability in Miller, her life marked by past trauma. Winslet lets this rawness out at key moments, bringing great depth and shade to a character who could otherwise be blunt and difficult, and the film works best when it gives her free reign.

It’s unflinching but also tasteful in its depiction of war. Experienced cinematographer and first-time film director Ellen Kuras shoots its grimy, hand-held immediacy with an intensity that makes a lot of the film’s limited budget. Lee’s dirt and dust-sprayed combat scenes – with Miller dodging explosions and bullets to get into position to get the perfect shot – are tensely assembled and make a punchy impact. But Lee also knows when not to show us things, and its visual restraint when Miller and colleague David Scherman (Andy Samberg) photograph the horrific aftermath of Buchenwald and Dachau is admirable, the camera focusing on the characters’ stunned faces as they capture the terrible moments, with the horrific reality just out of focus.

There are some fine moments in Lee, which makes it more of a shame that so much of it feels safe, predictable and unchallenging. Lee focuses on Lee Miller as an artist and downplays her daring, unconventional life. Tellingly it’s adapted from a biographer by her son, titled The Lives of Lee Miller, which chronicles her life of constant reinvention. This is after all a woman who maintained a relationship with her Egyptian husband in the 30s, after meeting her second husband Roland who himself remained married for several years (they only married in 1947). She was a model, a surrealist artist, photographic pioneer, ahead of her time. That’s rinsed out to make her more conventional.

In the film, she and husband Penrose (a generously low-key performance from Alexander Skarsgård) have an uncomplicated meet-cute in a French villa owned by a friend (an extended cameo by Marion Cottillard) – admittedly it as at an outdoor picnic where Lee and others sunbathe topless – before settling into a life of middle-class suburbia (right down to Lee cooking meals for Roland when he returns from work). Hints that she has a consensual affair with Scherman linger, but the film seems prissily determined to reposition Lee as a far more conventional person than she really was. It’s a conservative attitude that comes from a good place – focusing on the work not the gossip – but it also makes her feel less unique or challenging than she was.

With the work as its focus, it’s surprising Lee doesn’t make more of the extensive collection of masterpiece photos Miller took. Although an inevitable credits montage shows how some of these were re-created for the film, actually including the images in the film itself might have carried more power and placed Miller’s work more prominently at its heart.

Lee also fumbles slightly with its final revelation of Miller’s past trauma. Shocking as this is, attempting to suggest what happened to Lee in her teens is on the same scale as the Holocaust or that she has a unique understanding of an act of ethnic genocide because she suffered in the past stinks. It’s especially notable since Lee does an excellent job of showing the quiet distress the Jewish Scherman feels as he realises only an accident of geography saved his life. Andy Samberg, in his first dramatic role, is extremely good in a role that clearly carries a very personal feeling for him.

Lee has things going for it, not least Winslet’s barn-stormingly committed and passionate performance. But in the end, it turns its lead character into someone who feels less provocative and revolutionary than she was. Its safely traditional structure and narrative approach turn her into a “role model” and make Lee the sort of middle-brow biopics Hollywood churned out in the 80s. It’s solid, interesting but essentially safe and forgettable.