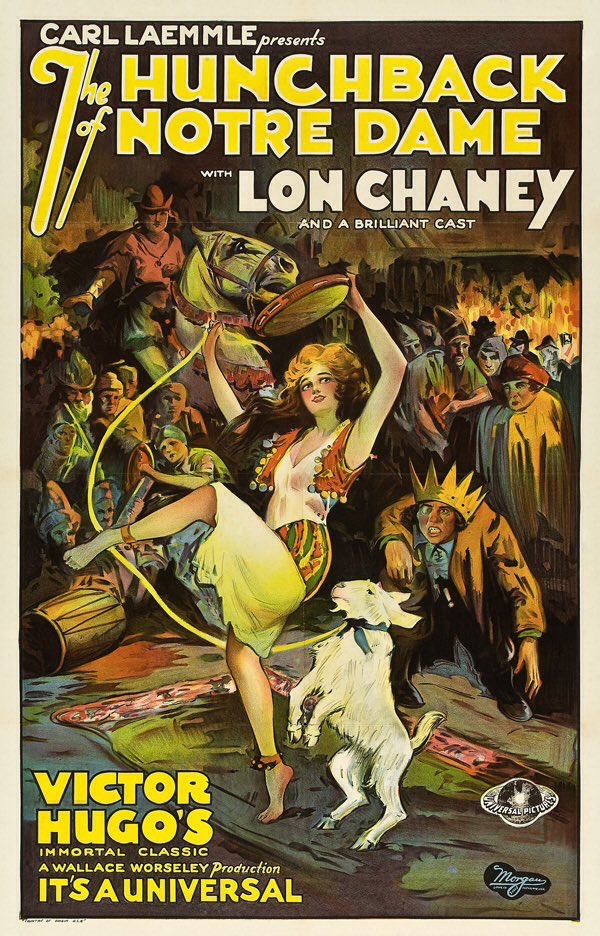

Chaney establishes his own legend in this crowd-pleasing epic, shot on the grandest scale

Director: Wallace Worsley

Cast: Lon Chaney (Quasimodo), Patsy Ruth Miller (Esmeralda), Norman Kerry (Phoebus de Chateaupers), Kate Lester (Madame de Gondelaurier), Winifred Bryson (Fleur de Lys), Nigel de Brulier (Dom Claud), Brandon Hurst (Jehan), Ernest Torrance (Clopin), Tully Marshall (Louis XI), Harry van Meter (Mons. Neufchantel)

If any film cemented Lon Chaney’s reputation as ‘Man of a Thousand Faces’ it was this. Chaney knew Quasimodo was a gift for him, securing the rights for himself and shipping them around the major studios until Universal Studios bit. Setting up the project as a ‘Super Jewel’ (with Chaney taking a handsome pay cheque), a near full scale reproduction of the exterior (and many of the interiors) of Notre Dame was built on the Universal set and the film became a smash hit.

Quasimodo (Lon Chaney) is the frightful bellringer of Notre Dame cathedral, a lonely hunchbacked man, mocked and scorned by Parisians. Half-deaf after years of bellringing, he is in thrall to his master Jehan (Brandon Hurst), brother of the saintly Dom Claud (Nigel de Brulier). Jehan tasks Quasimodo to kidnap the beautiful Roma girl Esmeralda (Patsy Ruth Miller), adopted daughter of Clopin (Ernest Torrance), ‘king’ of the beggars. It fails, but the arrested Quasimodo is treated with kindness by Esmeralda and falls in love with her. Esmeralda though is in love with roguish captain Phoebus (Norman Kerry), only to be accused of attempted murder after the jealous Jehan stabs him. Quasimodo rescues Esmeralda as the city collapses into revolt.

Brilliantly assembled by producer Carl Laemmle, Hunchback looks amazingly impressive. The reconstruction of Notre Dame (and the square around it) is genuinely stunning in its scale and detail. (Surely thousands of viewers believed it’s the real thing!) The sets inside the cathedral skilfully use depth perception to create cloisters that seem to go on forever. Crowd scenes fill the film with vibrancy: from the off, with its medieval feast of fools, it’s a dynamic explosion of energy, with everything from men dressed as bears to dancing skeletons, full of raucous naughtiness. Later battle scenes (including a cavalry charge) before Notre Dame’s doors brilliantly use the sets striking height.

The film’s finest effect though is Chaney’s Quasimodo, a portrait of sadness and timidity under an aggressive frame. Chaney’s physical dexterity and ability to bend and twist his body is put to astonishingly good effect, as a he swings on bells, clambers up and down the set and contorts his body into a series of twisted shapes that drip of pathos. He finds a childlike innocence in this man who knows virtually nothing of the real world and latches onto those who show him affection with a puppy-like adoration.

The film’s finest sequences show-case Chaney: whether that’s following his graceful descent down the walls of Notre Dame or seeing his fear and vulnerability exposed in front of the crowd. In a film of such vastness, perhaps its most striking moment is one of genuine intimacy. Tied to a wheel for a public lashing (taking the rap for Jehan’s misdeeds), Chaney retreats into shame and fear and recoils in terror when Esmeralda approaches him – only to soften and almost collapse into a pool of gratitude when she tenderly offers him water rather than the abuse the crowd gives him.

It’s a striking testament to Chaney’s mastery of physical transformation, but also his ability to humanise those who appear as monsters. Quasimodo’s genuine love for Esmeralda is very sweet, as his bubbly excitement at experiencing such feelings for the first time. Chaney’s determination to protect Esmeralda at all costs (including misguidedly defending Notre Dame from a gang of beggars as bent on protecting her as he is) is very touching. It’s a genuinely great performance.

The Hunchback of Notre Dame cemented the public image of the novel – most of the (many) later versions that followed used it as an inspiration. For starters, it moved Quasimodo into the most prominent role. Forever more, the public image of the novel was a lonely, tragic man, swinging on bell ropes and shouting sanctuary. Not just that: this film started a trend of splitting the novel’s hypocritical churchman Frollo into two characters (here a noble priest and his villainous brother) to avoid making a man of the cloth a villain. It also started the ball rolling on re-interpretating the selfish Phoebus as more of a matinee-idol romantic figure. Not to mention seeing the film as a gothic-laden, semi-romance with Hugo’s social and political commentary utterly shorn off.

Today we only have a reduced road-show cut of the film. This does mean Hunchback sometimes rushes or abandons plot points, or swiftly cuts off scenes with an occasional abruptness. An entire plot strand of Eulalie Jensen’s deranged old woman (secretly the mother of Esmeralda) is utterly abandoned without any emotional conclusion. Tully Marshall’s Louis XI pops up for a few brief scenes only to be ditched with brutal abruptness. Phoebus’ initial fiancée Fleur du Lys and her mother emerge for a few key scenes to be all but forgotten by the close.

Hunchback ditches many of the novel’s complexities. As mentioned, Phoebus – in the book a creepy semi-rapist – becomes a conventional romantic leading man. Hunchback has echoes of his novel’s more ambiguous original: his first scene flirting with Esmeralda features a cut to a spider spinning a web and Louis XI openly calls him a rogue. But his affection for Esmeralda is treated as genuine, allowing the film to excuse his shabby treatment of Fleur de Lys. Norman Kerry does his best with all this, although the audience is far more invested in Quasimodo’s unrequited love for Esmeralda.

Similarly, the social commentary around the beggar’s, led by a charismatic Ernest Torrence as Clopin, gets shaved back. Hunchback throws in a snide comment about ‘justice’ under Louis in its title cards as Quasimodo is thrashed for Jehan’s crimes and Esmeralda’s receives a farcical trial for murder (despite her ‘victim’ Phoebus still being alive) concluding with an iron boot being screwed onto her foot to extract a confession. But the beggar’s campaign for justice gets short-changed in the cut, and it’s just as easy to see them as a gang of troublemakers (who need to be restrained from a lynching at one point by Esmeralda).

Hunchback was directed by Wallace Worsley after other options, including Erich von Stroheim, Tod Browning, Raoul Walsh and Frank Borzage were rejected over concerns about their lack of budget control (an odd concern, seeing as they built a 225-foot replica of the lower front of Notre Dame, including each individual carving and gargoyle). Worsley brings professionalism, marshalling the vast crowd with great skill – promotional material made huge play of him casting aside his megaphone in favour of a radio to control the huge cast. There are few moments of genuine visual originality or inspiration in Hunchback, but Worsley captures the scale with some fine camerawork (especially striking images looking down from the top of Notre Dame).

Hunchback is an epic drama, a grand melodrama with a brilliant performance by Chaney. However, you can argue its focus is on entertainment rather than cinematic skill. There are genuinely very few truly memorable shots. It feels like a producer’s film, where resources are expertly managed and the money spent is all up on screen. But when its’ put up there as entertainingly as this, who can complain about that?