Guilt and shame under the politeness in this stagy and almost-very-brave Rattigan adaptation

Director: Delbert Mann

Cast: Rita Hayworth (Anne Shankland), Deborah Kerr (Sibyl Railton-Bell), David Niven (Major David Angus Pollock), Burt Lancaster (John Malcolm), Wendy Hiller (Pat Cooper), Gladys Cooper (Mrs Maud Railton-Bell), Cathleen Nesbitt (Lady Gladys Matheson), Felix Aylmer (Mr Fowler), Rod Taylor (Charles), Audrey Dalton (Jean), May Hallett (Miss Meacham), Priscilla Morgan (Doreen)

Bournemouth’s Hotel Beauregard offers comfortable rooms and separate tables for dining. No wonder it’s popular with a host of regulars and out-of-town guests. But at each of those separate tables, drama lurks. Unflappable Pat Cooper (Wendy Hiller) manages the hotel and is secretly engaged to John Malcolm (Burt Lancaster), a down-on-his luck writer a little too fond of a pint in The Feathers. Their secret relationship is thrown into jeopardy when John’s ex-wife Anne (Rita Hayworth) arrives from New York, keen to get John back. Meanwhile, Major Pollock (David Niven) hides a secret behind his “hail-fellow-well-met” exterior, one which will threaten his place in the hotel and friendship with mousey Sibyl (Deborah Kerr) – a woman firmly under the thumb of her domineering mother (and resident bully) Mrs Railton-Bell (Gladys Cooper).

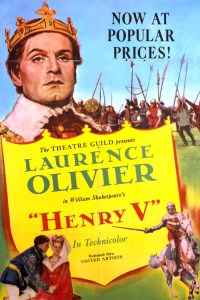

Delbert Mann’s film merges two Terence Rattigan one-act plays into a single, respectable piece of middle-brow Masterpiece Theatre viewing, which Mann subsequently effectively disowned (even after its seven Oscar nominations) after losing control of both editing and scoring to producer Lancaster. (Mann, quite rightly, loathed the hilariously out-of-place Vic Damone crooner number “Separate Tables” that opened the film.) Mann had already replaced Laurence Olivier, who dropped out after Lancaster’s company felt the film needed two American stars to make it box-office (handily they chose Lancaster himself and his business partner’s fiancée Rita Hayworth).

Lancaster and Hayworth are incidentally the weak points in the cast, their Americanness hopelessly out of step with Rattigan’s extremely English style and setting. Both actors are all too clearly straining to “stretch themselves” in unlikely roles, giving the film a slight air of self-indulgence. (Hillier later archly stated her best scene from the original was handed to Hayworth, while Lancaster recut the film to move up his first entrance.) The will-they-won’t-they tug-of-war between the two of them is Separate Tables’ least interesting beat and it’s to the film’s detriment that it, and these two awkwardly miscast actors, dominate so much of the film’s middle section.

They were already playing the dullest half of Rattigan’s double bill. Rattigan’s passion, and by far the film’s most electric moments – even if they only really constitute just under a half the runtime – revolve around the scandal of Major Pollock. Pollock, it is swiftly revealed, is not only prone to exaggerate his class, schooling and military career (his knowledge of alleged alma mata Sandhurst and the classics is revealed to be sketchy at best) but also carries a secret criminal conviction for harassing young women in a cinema.

While such harassment is of course recognised as beyond the pale today, it’s very clear in Separate Tables that Pollock’s misdeeds are standing in for a crime that literally “dare not speak its name”. Rattigan was one of Britain’s most prominent closeted homosexuals and his original intention had been for the Major’s crime to be fumbled cottaging. In the 50s it was unspeakable for the lead to be a sympathetic frightened homosexual so, in what looks bizarre today, it was far more acceptable to make him a timid sexual molester. However, the subtext is very clear, unspoken but obvious. One only has to hear the tragic Major sadly say “I’m made in a certain way and I can’t change it” and talk about his shame and loneliness to hear all too clearly what’s really being talked about here. Isn’t the Major’s pretence about being “the Major” just another expression of the double life a gay man had to lead in 1950s Britain?

This sensitive and daring plot is blessed with a wonderfully judged, Oscar-winning performance by David Niven (dominating the film, despite being on screen for a little over 20 minutes – the shortest Best Actor winning performance on record). Niven had made a career of playing the sort of suave, debonair military-types Pollock dreams of being – so there might not have been an actor alive more ready to puncture that persona. Recognising a role tailor-made for him, Niven peels away the Major’s layers to reveal a shy, sensitive, frightened man, desperate for friendship and acceptance. His heart-breaking confession scene (clearly a coded coming out) is beautifully played, while the closing scene with its hope of acceptance gains hugely from Niven’s stiff-upper-lip trembling with concealed emotion.

Niven’s performance – (Oscar-in-hand he rarely felt the need to stretch himself as an actor again) – centres the film’s most dramatic and engaging content. The campaign against the Major is led by Mrs Railton-Bell, superbly played by Gladys Cooper as the sort of moral-crusader who needs to cast out others to maintain her own ram-rod self-perception of virtue. Cooper uses icy contempt and overwhelming moral conviction to browbeat the rest of the guests in a sort of kangaroo court into blackballing the Major, a neat encapsulation not only of the power of the loudest voice but how readily decent people reluctantly acquiesce to it to avoid trouble.

Her control has also crushed her daughter’s spirit. Deborah Kerr’s performance is a little mannered: Kerr works very hard to embody a mousey, dumpy, frumpy spinster and make sure we can see she’s doing it. But she works beautifully with Niven and her meekness means there is real impact when the mouse finally (inevitably) roars. The rest of the guests are a fine parade of reliable British character actors: Felix Aylmer reassuringly fair and May Hallett particularly delightful as a no-nonsense woman who doesn’t give a damn what people think and trusts her own judgement.

Linking all plots together, Wendy Hiller won the film’s other Oscar as the hotel manager. Hiller was born to play decent matrons, bastions of respectable fair play who reluctantly but stoically bear personal sacrifices as their own crosses. She’s a natural with Rattigan’s dialogue and brings the best out of Lancaster, as well as providing all the drama (and sympathy) in the film’s other plotline as a surprisingly noble “other woman”.

Separate Tables is a middle-brow slice of theatre filmed with assurance. But when it focuses on Major Pollock it touches on something far more daring and much more moving than anything else it reaches for. Here is true low-key, English tragedy: under a clear subtext, we see the horror of a man who pretends all his life to be something he is not and the terrible judgements from others when he is exposed. It’s that which gives Separate Tables its true impact.