A bubbling soap full of incidents, disguising itself as a meditation on philosophy

Director: Edmund Goulding

Cast: Tyrone Power (Larry Darrell), Gene Tierney (Isabel Bradley), John Payne (Gray Maturin), Anne Baxter (Sophie MacDonald), Clifton Webb (Elliott Templeton), Herbert Marshall (W Somerset Maughm), Lucile Watson (Louisa Bradley), Frank Latimore (Bob MacDonald), Elsa Lanchester (Miss Keith), Cecil Humphreys (Holy Man), Fritz Korner (Kosti)

“What’s it all about?”: a question asked long before Alfie and it’s the one asked by Larry Darrell (Tyrone Power) as he returns from World War One to Chicago. Suddenly those garden parties and country clubs all look rather empty and shallow. Larry is engaged to Isabel (Gene Tierney), but he’s not interested in office work and domesticity. He wants to live a little bit, to find out what life is about. Doesn’t he owe that to the man who died in the war to save his life? With just $3k a year (over $50k today, which must help), he heads for the artistic life in Paris. After a year apart, Isabel decides it’s for her (£3k a year? What kind of life is that!) and marries a banker so dull he’s literally named Gray (John Payne). Flash forward to 1929 and the Crash has upturned the lives of the Chicago bourgeoisie – perhaps Larry’s inner contentment will mean more after all?

Adapted from W Somerset Maugham’s novel – with Maugham as a character, played by the unflappably debonair Herbert Marshall – The Razor’s Edge is a luscious period piece with pretentions at intellectualism but, rather like Maugham, is really a sort of a soapy plot-boiler with a veneer of cod-philosophy. Not that there’s anything wrong with that – after all the suds in Razor’s Edge are frequently rather pleasant to relax in – but don’t kid yourself that we are watching a thoughtful piece of cinema. It’s closer in tone to Goulding’s Oscar-winning Grand Hotel than it might care to admit.

Our hero, Larry Darrell, should be a sort of warrior-poet, but to be honest he’s a bit of a self-important bore. Played with try-hard energy by a Tyrone Power desperate to be seen as a proper actor rather than action star, Larry has a blissful “water off a duck’s back” air that sees him meet calamity with a wistful smile and the knowledge that providence evens everything out. Be it the break-up of an engagement or the death of close friend, little fazes Larry who has a mantra or piece of spiritualist advice for every occasion. Bluntly, our hero is a bit of a prig whose middle-class spirituality has all the mystical wisdom of a collection of fortune cookies.

It’s no real surprise that the film’s weakest parts are whenever Larry engages with the vaguely defined collection of homilies and mumbo-jumbo he picks up about spirituality. All this culminates in an almost embarrassingly bad sequence in the Himalayas, where Larry stays under the clichéd tutelage of a shoe-polish-covered Cecil Humphrey as a Holy Man whose every utterance is a vague collection of Diet Yoda aphorisms. Larry, with all the self-importance of the financially secure middle class, returns to the West sublimely certain of his own higher contentment and rather patronisingly looking down on the rest of the characters as shallow, grasping bourgeoisie.

The Razor’s Edge’s insight into human spirituality essentially boils down to “step out of the rat race and you’ll be a better man” – again made much easier, since Larry “forsakes” worldly wealth but can still dapperly turn out to a fancy function in a perfect tux. To be honest it becomes a bit wearing to see the other characters treat him like a sage and more than a bit mystifying why Isabel remains stubbornly obsessed with him for her whole life.

But if she wasn’t, we’d lose a large chunk of the appeal of the movie. The Razor’s Edge’s philosophy may be paper thin, but as a soap it’s spot on. And the scheming, manipulative, vindictive, snobby and entitled Isabel is a gift of a part, seized with relish by Gene Tierney. Isabel wants Larry, not so much because of who he is but because he belongs to her, and she can’t believe he was willing to let her jilt him without a fight. The epitome of the self-obsession of the modern age that Larry has rejected, Isabel consistently puts herself first, clings to the luxuries of high living and can barely hide her bored disinterest in the tedious Gray (a perfect role for the solid but uninspiring John Payne). Isabel schemes and attempts seduction of the saintly Larry, and her hissable antics provides The Razor’s Edge with much of its enjoyable thrust.

Because as a soap is where this film is most happy. It’s actually very well staged and shot by Goulding, full of carefully considered camera moves (including a late “wham” line which we don’t see a character react to, leaving their response open to our interpretation) and skilfully using depth of plain to showcase a series of luscious sets and impressively recreated Parisian streets on sound stages. The Razor’s Edge has a lot of very professional Hollywood craft behind it.

Its event-filled sub plots also give a host of excellent scenes and fun dialogue to its supporting cast. Anne Baxter won an Oscar as the tragic Sophie, a bubbly socialite (and old flame of Larry’s) from Chicago, whose husband and baby are killed in a car accident, tipping her into years of alcoholism and (it’s implied) life as a “good-time-girl” in a seedy Parisian bar. Baxter seizes this role for what it’s worth, from initial charming naivety to tear-streaked discovery of her bereavement to fidgety attempts at sobriety after Larry decides to marry her to keep her on the straight-and-narrow (needless to stay, temptation is put in the way of the pacing, smoking, fist-forming Sophie by the blithely shameless Isabel). It’s a very effective and sympathetic performance.

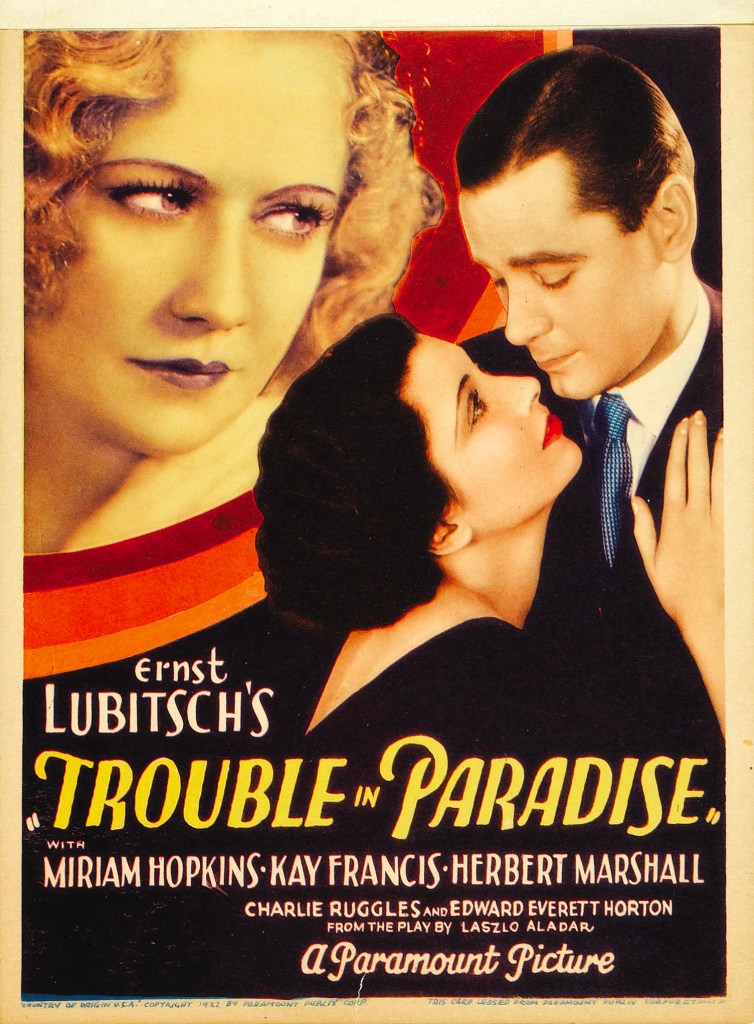

Clifton Webb, at the time Hollywood’s leading waspish figure of camp, has an Oscar-nominated whale of a time as Elliot Templeton, preening but generous socialite, delighting the finer things in life (from fine wines to perfectly stitched dressing gowns) who provides a catty sounding board to Isabel and whose final hours are spent bemoaning being snubbed by a countess. Herbert Marshall delivers a perfect slice of British reserve and gently arch commentary as Maugham (the real Maugham prepared a script which was junked by the studio, ending his Hollywood career there and then), purring his dialogue with his rich, velvet tones.

It serves to remind you that The Razor’s Edge works best as an event-packed piece of social drama, which it swiftly becomes as deaths, tragedy, alcoholism, scheming and feuds pile on top of each other in the second half with the blissful Larry casting a quietly judgemental but kind eye over everything around him. For all its attempts to look into the human condition, this is where The Razor’s Edge is at its best: engaging supporting characters and a hissable villain, all leading to a series of juicy plot developments. For all its literary pretentions, it’s at best a shallow From Here to Eternity.