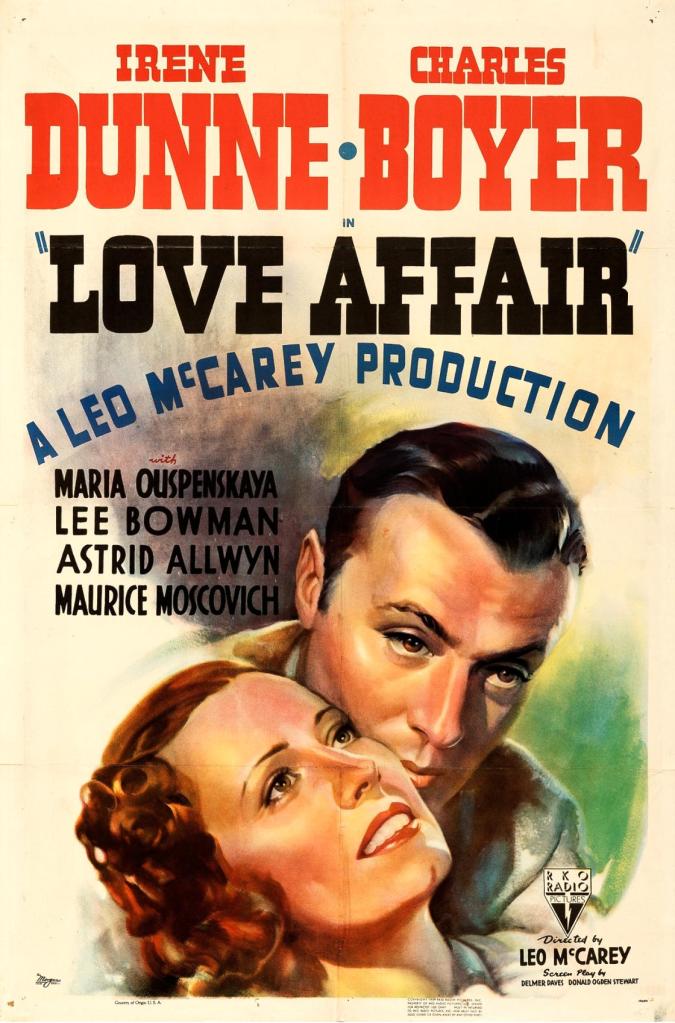

Two people in love, separated by circumstance, in this film of two halves: one comedy, one sentimental

Director: Leo McCarey

Cast: Irene Dunne (Terry McKay), Charles Boyer (Michel Marnay), Maria Ouspenskaya (Michel’s Grandmother), Lee Bowman (Kenneth Bradley), Astrid Allwyn (Lois Clark), Maurice Moscovich (Maurice Cobert)

In many ways you could say Love Affair was the turning point in Leo McCarey’s career. For years in silent films and the early talkies he had been one of Hollywood’s leading comedy directors, the quick-witted master of the improvisational pun. But there was a second McCarey: the devout Catholic, concerned about social issues. The McCarey who light-heartedly complained when was given an Oscar for The Awful Truth rather than his heartfelt critique of elderly care, Make Way For Tomorrow. This McCarey increasingly leaned into well-meaning, sentimental dramas.

So why is Love Affair a turning point? Because the first half is a charming, funny, sexy meet-cute: and the second a well-meaning but sentimental love story that pulls two people apart. Those meet-cuters are famous Parisian playboy (he’s basically a gigolo) Michel Marney (Charles Boyer) and nightclub singer Terry McKay (Irene Dunne). They meet on a trans-Atlantic liner and fall in love. Problem is they are both engaged to others (both of them rich), waiting for them in New York. Should they decide to chuck it in and be together, they arrange to meet six months later at the top of the Empire State Building. Come the day, Michel waits – but on the way there, Terry is hit by a car and possibly left paralysed. She doesn’t want to tell him. He thinks she never planned to show up. Will they ever be together?

That car crash is the pivot in a film that feels like two genres surprisingly successfully wedded together. Love Affair is a great idea (so good in fact that McCarey remade it about 20 years later as An Affair to Remember), a romantic story with all the joy and vibrancy of a couple finding each other and falling in love, then the painful sting of tragic circumstances pulling them apart. It manages to be sweetly funny and then more or less manages to land just the right side of sentimental (though, lord, it skates near to the edge).

You go with that more overtly manipulative conclusion though, since the subtle comedic and romantic manipulation of the first half is so well done. McCarey encouraged his actors to improvise: filming started with McCarey sitting at a piano, plinking keys, waiting for inspiration to jazz up the script. It’s an approach many actors found challenging (Cary Grant nearly had a meltdown at first on The Awful Truth). But he found the perfect pairing with Boyer and Dunne.

Of course, Irene Dunne was a veteran. An actress far too overlooked today, Dunne flourished under McCarey’s style. Here she’s gloriously warm, sexy and charming. Terry McKay has a very dry (at times almost slightly smutty) wit; she’s absolutely no fool, but also kind, caring and considerate. Dunne sparkles every time she steps in front of the camera, displaying the sort of comic timing you can’t buy (her teasing glances at Michel during their first meeting, when she accidentally reads a telegram all about his sexual exploits at Lake Como, are to die for). But her face also lights up with a genuine radiance as she finds herself falling in love.

She also sparks wonderfully with Charles Boyer. Another overlooked star of 1930s Hollywood, Boyer was desperate to work with McCarey. He found the improvisational style awakened a relaxed, playful element in his acting that helped make Michel exactly the sort of dreamboat you could imagine falling in love with on a cruise. Boyer was also a superb reactor, his face able to communicate anything from growing interest, to delight and also piety, pain and disappointment. Boyer’s comic timing, like Dunne’s is faultless. Like her, he also effortlessly shifts to drama in the second half, expertly demonstrating the maturity of a playboy into someone generous and understanding.

With these two actors, McCarey couldn’t go too far wrong. Their natural ease with each other makes for wonderful chemistry. They are two people who progress naturally from teasing, to enjoying each other’s company, to realising they enjoy each other’s company way too much. Today, Love Affair can look a little tame – they don’t even kiss (although one shot of crashing waves, cutting to them opening a door on the boat to walk along the deck together, is rather suggestive). But the point is that this is love not an affair (or an affair about love). The feelings they develop for each are genuine and, bless them, they don’t want to corrupt it with behaviour that could compromise them.

Tellingly their love is cemented during a stop off in Madeira, where they visit Michel’s aunt (played by an archly eccentric Maria Ouspenskaya). She welcomes them into her home, bonds with Terry, and Michel shows Terry a far different side to himself than his playboy persona: a thoughtful artist. McCarey even shoots them together (in a beautifully lit scene by photographer Rudolph Maté) in a chapel, kneeling side-by-side at the altar. Could McCarey make the endorsement of their love more clear?

Perhaps he felt he needed to, since the screenplay was controversial. The Hays Code had no intention of allowing a film showing two engaged people walking out on their partners. Perhaps that’s why they needed to be “punished” with that sudden car crash. The second half is less successful: maybe because I find the “I can’t ruin his life by making him look after me in a wheelchair” a little too on the nose. Boyer and Dunne play the hell out of it: Dunne is quietly crushed under a surface of charm and what-will-be-will-be. Boyer tries his best to hide his pain, but still searches for some of what he’s lost in his new career as an artist.

Of course, the truth will out – and it will end happily. But there’s a little too much sentiment in the second half, after the heartfelt romancing of the first. A little too much put-a-brave-face-on-the-pain, a few too many contrivances to maintain the illusion (of course they go to the same play on Christmas Eve!). There are too many sickly sweet scenes of Dunne singing with the kids at the orphanage she’s recuperating at (a ghastly advance warning of McCarey’s tedious Going My Way). But it just about works, because we really care about Terry and Michel. We want them to be together, come what may.

Love Affair can be a mixed bag, but it’s got two wonderful performances for Boyer and Dunne (she was nominated, he was robbed) and McCarey manages to juggle comedy, romance, sweetness and a little touch of sadness. It’s a luscious romantic film, even while you see it manipulating you – and for that, it will always give you a great deal of pleasure.