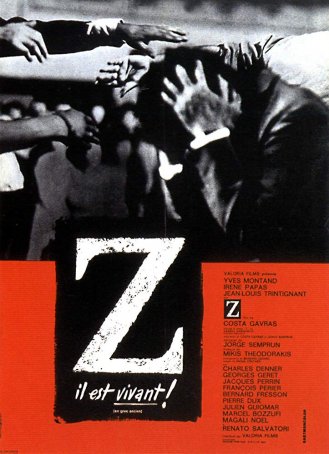

Costa-Gravas thrilling conspiracy thriller is possibly one of the finest political films ever made

Director: Costa-Gravas

Cast: Jean-Louis Trintignant (Examining Magistrate), Yves Montand (Deputy), Irene Papas (Helene, the Deputy’s wife), Pierre Dux (General), Jacques Perrin (Photojournalist), Charles Denner (Manuel), François Périer (Public Prosecutor), Georges Géret (Nick), Bernard Fresson (Matt), Marcel Bozzuffi (Vago), Julian Guiomar (The Colonel), Gérard Darrieu (Barone), Jean Bouise (Georges Pirou), Jean-Pierre Miquel (Pierre)

Costa-Gravas Z is an explosive political thriller, ripping a lightly fictionalised story from the Greek headlines (the opening credits playfully state ‘any resemblance to real people is ‘purely intentional!’) and turning it into a compellingly angry, cold-eyed look at political repression. It was based on the state-backed murder of Greek politician Grigoris Lambrakis in 1963 and the investigation by magistrate Christos Sartzetakis which briefly looked like it might expose repressive military forces but actually kick-started a 1967 military junta counter coup in Greece. Z takes this as inspiration for a truly universal story that continues to feel like ‘it could happen here’.

Lambrakis becomes The Deputy, played with great charm and determined charisma by Yves Montand. After death threats, he is murdered after a political rally by two thugs in a hit-and-run, in a public square, surrounded by police officers and a legion of witnesses. The police, represented by the virulent anti-communist General (Pierre Dux) declare it a tragic accident. They firmly expect our Sartzetakis-figure (Jean-Louis Trintignant, putting his enigmatic unreadability to extraordinarily good-use), son of a war hero, to back-up their bullshit. But he didn’t get the memo, conducting a genuine investigation which reveals the extensive links between the military and police and far-right organisations, how they planned the hit and did everything to ensure its success. But will this investigation lead to real change?

Costa-Gravas’ film is a hard-boiled conspiracy thriller with echoes of The Battle of Algiers’ primal urgency and immediacy. It’s committed to throwing you into the middle of the turmoil, with fast-cutting, hand-held camerawork, tracking shots through crowds and shots which zero in on the faces of victims and perpetrators alike. The film’s influence on directors like Oliver Stone is palpable. But, unlike Stone’s work, Z wears its moral outrage carefully: it presents events with a journalistic matter-of-factness, trusting us to recognise the corrupt horror of over-mighty governments. The resolute professionalism of Trintignant’s magistrate helps enormously here – heroism in this world is being honest and doing your job.

What Costa-Gravas film reveals is that these authorities believe they can act with utter impunity, convinced they will never be questioned by anyone, other than their liberal targets. Z opens with a darkly comic scene that outlines this thinking: during a lecture, the pompous General outlines (to a military audience shown impassively watching in a series of quick reaction cuts) his theory of ‘ideological mildew’ attacking the ‘tree of liberty’, using a tortured pesticide metaphor to suggest it is their duty to kill the mildew (liberals and socialists). This tyrannical view is parroted by people who are neither lip-smacking villains or fiendishly clever – they just have absolute, fixed certainty.

Z makes clear that such men, placed in position of authority, will attempt to shape events with a breath-taking arrogance. The assassination plot is shockingly clumsy and obvious and cover-up so full of transparent bare-faced lies, you’d need to be impossibly arrogant to even consider you could get away with it. Copious evidence shows meetings between senior officers and members of the right-wing CROC group. It’s claimed the Deputy’s fatal head-wound came from hitting the pavement, even though this is ruled impossible by both an autopsy and hundreds of witnesses. The General claims not to know the driver who ‘rushed’ the wounded Deputy to hospital (stopping at every opportunity), even though the man is his personal chauffeur. Everyone repeats the same tortured, unusual phrases – from the head of police to the thugs themselves.

It doesn’t stop there. Once it becomes clear Trintignant’s magistrate is genuinely investigating – that he has his own mind and opinions – the clumsy cover up turns aggressive. Blame is put on the Deputies own supporters (the word ‘false-flag operation’ didn’t exist then, but the idea is seized on); his lawyer is almost killed in a park hit-and-run in front of dozens of witnesses; a witness who can testify to the plans of the hitmen is pressured, told he has epilepsy, framed as a radical (he’s clearly not) and then nearly assassinated by one of the hit-men (put up in the same military hospital with a pretend broken leg), who flees the scene and in front of his doctors, while giggling at his cheek.

Some of this is in fact blackly funny. It perhaps almost would be, if it wasn’t for Z’s moral indignation. Even without murder, this is a repressive, corrupt regime: the Deputy’s team have innumerable petty obstacles placed in their way for their rally, their supporters are openly attacked by bused in protestors mixed with baton-wielding under-cover officers. Costa-Gravas doesn’t show the Deputy as a saint – flashbacks reveal he is an adulterer – but it does make clear his bravery (confronting and cowing crowds of anti-liberal rioters, utterly unrestrained by the police), leadership and the fear he overcomes. It also shows, especially in Irene Papas’ emotionally underplayed but quietly devastating performance, the raw grief of those who love him. His closest colleagues weep at news of his death, the post-death slandering of him all-the-more disgusting.

Z presents its evidence with an increasingly overwhelming force. The magistrate corrects (for a long time) any use of the word murder for ‘accident’ – by the time he himself says ‘murder’ it’s almost easy for us to miss it, so natural has the conclusion become. Pressure is, of course, applied to him: senior officers bluster about metaphorical eggs and omelettes; his bosses suggest he charge only the hit-men and (for good measure) charge the Deputy’s people for disrupting the peace by holding the rally in the first place. Plenty of ordinary people know exactly what’s going on, but don’t want to take risks: a newspaper editor reports what he’s told to, the Deputy’s doctor regrets not joining his lonely ‘march for peace’ but, well, you know how it is…

Given the blatant criminality of the police and the army – and the sadistic arrogance of hit-man Vago (an uncomfortable beat in Z is the whiff of homophobia in the depiction of Vago as a predatory homosexual and pederast) – it’s truly triumphant to see them bought to book. Despite their bombast (each officer states he will have no choice but to take his life to avoid the shame, something of course none of them do), each flees the building railing at the press. (The General, an antisemite among everything else, even roars ‘Dreyfus was guilty!’ when a journalist compares the affair to that).

But it’s short-lived. Perhaps Irene Papas’ Helene knows it will be when she responds to news of the arrest with a quiet middle-distance stare. Z closes with a dark coda that could almost be funny if it wasn’t horrifying. A photojournalist (played by producer Jacques Perrin) who we have followed uncovering the plot, reports the aftermath: initial resignations followed by slap-on-the-wrist sentences for the hit-men, charges dropped for the officers and a coup d’etat (at this point a cut removes Perrin) which sees the arrest or ‘accidental’ death of all the Deputy’s supporters, a junta government and bans of everything from authors, mini-skirts, modern mathematics and, above all, the letter Z, as zi has been taken by protestors as the badge ‘He Lives’.

It would be funny. It almost is funny. If it wasn’t part of a system that crushes freedom with violence and murder. Costa-Gravas’ brilliant, engrossing and perfectly judged film shows how terrifyingly swiftly it can happen, how freedoms and justice can be strangled before our very eyes. Watching it today, you can’t imagine a time when it won’t be coldly, chillingly, terrifyingly relevant.