Handsomely staged and quietly influential production, full of invention and good ideas

Director: Max Reinhardt, William Dieterle

Cast: James Cagney (Bottom), Joe E. Brown (Francis Flute), Dick Powell (Lysander), Jean Muir (Helena), Victor Jory (Oberon), Verree Teasdale (Hippolyta), Hugh Herbert (Snout), Anita Louise (Titania), Frank McHugh (Quince), Ross Alexander (Demetrius), Ian Hunter (Theseus), Mickey Rooney (Puck), Olivia de Havilland (Hermia), Dewey Robinson (Snug), Grant Mitchell (Egeus), Arthur Treacher (Epilogue)

It says something about Hollywood’s back-and-forth relationship with Shakespeare, that Reinhardt and Dieterle’s film can still make a case for being one of its finest Hollywood Shakespeare films. What’s fascinating about it is how much attitudes towards it have changed over time. Opening to a chorus of sniffs from the critics (“It should never have been filmed!”), horrified about the blasphemy of the Bard on celluloid, the things praised at the time now feel the stuffiest while the elements criticised feel fresh and dynamic. Personally, it’s crazy mix of genres, eras, comedic styles and dramatic tone feels like the sort of thing Shakespeare (a consummate showman who spoke in poetry) might have enjoyed.

It came about because Jack Warner wanted a bit of class. Max Reinhardt, internationally famous avant-garde theatre director, as part of Warner’s power thruple: direction by Reinhardt, music by Mendelssohn, words by Shakespeare! Reinhardt had directed a lavish production at the Hollywood Bowl (which also featured Rooney as Puck and de Havilland as Hermia), that would form the basis of his film, incorporating ballet and impressive visual effects. William Dieterle, was bought in to translate Reinhardt’s vision to film (since it quickly became clear Reinhardt didn’t know how to make a movie).

We get an MND that mixes farcical comedy with a dark, sensuous energy. Athen’s forest was transformed by Hal Mohr’s Oscar-winning photography into a glittering fantasy land, created with a mixture of superimposition and miles of cellophane wrapped around the perfectly-recreated trees to reflect the studio lights in a shimmering dance. But in this, is a fairy world of danger and chaos: Reinhardt’s pioneered the interpretation of Puck (played with malicious gusto by Mickey Rooney) as a fire-lighting child, revelling in the chaos his actions cause. Rooney (or rather his double, as Rooney broke a leg early in production) skips and sways, laughing maniacally, tormenting the lovers (possibly even controlling their words and actions), unleashing dark forces of the night.

The film is full of such dark forces – a surprise to critics who saw Dream as a gentle comedy. The ballet sequences, used by Reinhardt to visually demonstrate Oberon’s and Titania’s power to manipulate the environment around them, feature demonic dancers who wouldn’t look out of place in Faust, creepy music-playing goblins and a constant sense of unknowable power. Victor Jory – highly praised at the time, although his precise, poetic reading feels austere and lacking in feeling today – is a darkly imperious Oberon, with barely a trace of warmth to him. (Anita Louise’s Titania also takes a traditional line, speaking with a slightly irritating sing-song that should serve the poetry but instead drains it of life.)

You suspect, if he could have got away with it, Reinhardt might have allowed a trace of bestiality to enter into Titania’s romance with the transformed Bottom. As it is, he settles for Titania snatching a coronet from the Indian boy (nicely introduced early, to cement the split between the two fairy monarchs) who bursts into tears, increasing the feeling that the fairies are inconsistent, temporary creatures, perfectly willing to drop previously treasured people for whoever else captures their attention.

Lavish spectacle runs throughout a play that feels highly indebted to Raphael and the other Renaissance masters. Reinhardt has no problem switching styles: Theseus’ arrival is staged like an Ancient Roman pageant, before settling into a Renaissance style court while the Mechanicals could have stepped straight out of Brueghel. Again, it’s a playing around with style and location that looks very modern today but short-circuited reverentially literal critics at the time. Reinhardt even plays with the idea of Hippolyta being a less-than-willing partner for Theseus (she appears defiantly restrained in the opening scene), although this is largely benched for later scenes.

The lavish opening also shows the production’s ability to balance comedy and drama. Alongside the traditionalist grandiosity, we have low comedy from both the lovers and mechanicals. In a fast-cut, skilfully assembled array of moments (surely Dieterle’s work), the relationships between the four lovers are expertly displayed and mined for comic energy (particularly Lysander’s and Demetrius’ private competition to sing loudest) as are those between the mechanicals (from Bottom’s enthusiasm to Quince’s frustration at the terminal stupidity of Flute).

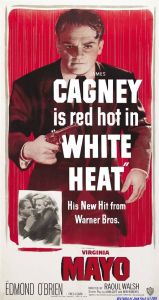

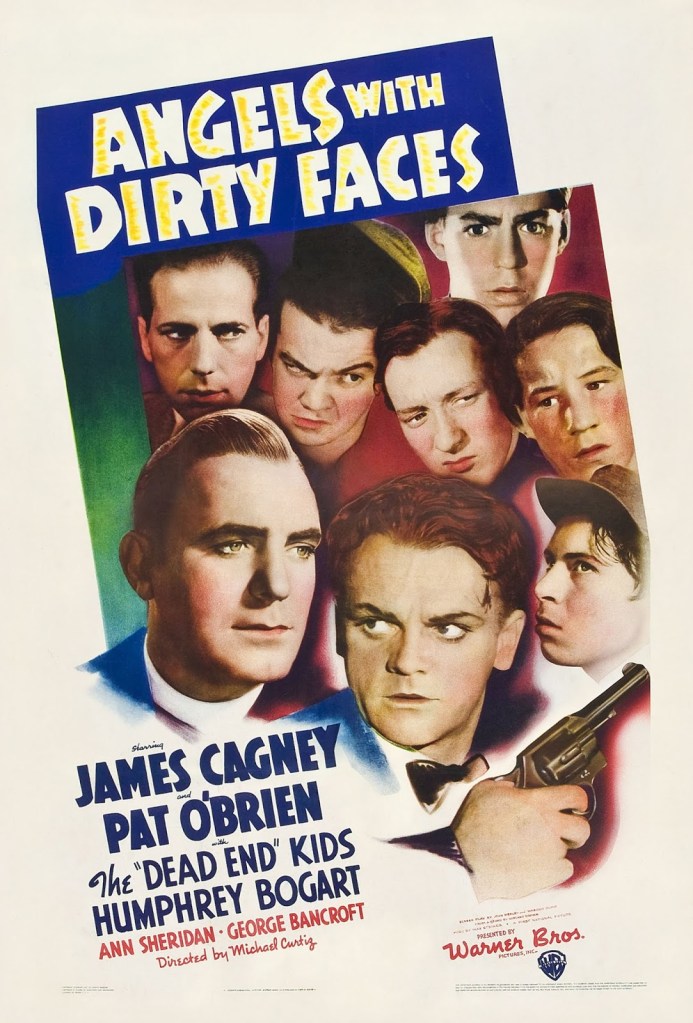

The mechanicals are one of the greatest divergence in critical opinion between then and now. To critics at the time it was a jaw-dropping mistake to cast Cagney and a host of film comedians in Shakespeare – surely these were roles for the likes of Gielgud? Everything from their delivery to the posture was lambasted for being crude and too damn American for a genre considered the exclusive preserve of the well-spoken likes of Jory and Hunter. However, the energy and naturalness of these actors – and the consummate comic timing they pull out of their roles – is one of the film’s greatest touches.

Cagney was never afraid to look beat-up or ridiculous, and he revels as an explosive ball of energy as Bottom. He flings himself, with the same energy as Bottom, into over-enunciated voices and grand displays of ‘bad acting’, parodying a host of styles from classical to pantomime to stage comedy. Cagney also makes him sweetly naïve and childishly literal, while his gentle, polite mystification about being treated like a king by the fairies seems rather sweet. The other mechanicals are also genuinely excellent, doing one of the hardest things: making Shakespearean comedy work on screen. Joe E Brown is hilarious as a supernaturally dim Flute, barely able to remember what gender he is playing; Hugh Herbert’s Snout has an infectious nervous giggle he can’t control, Frank McHugh’s Quince parodies directors like DeMille. Each of them contributes to a genuinely funny Pyramus and Thisbe that closes the film.

It’s more funny than the sometimes-forced banter between the lovers, not helped by a far too broad performance by Dick Powell (who later claimed he didn’t understand a word he was saying) that makes Lysander somewhere between a buffoon and an egotist. Olivia de Havilland (perhaps not surprisingly) emerges best here as a heartfelt Hermia, although the quarrel between the lovers is perhaps the least well staged sequence in the film (Reinhardt and Dieterle resort to all four of them at points speaking their lines at the same time, as if wanting to get the scene over and done with).

But MND is awash with other touches of cinematic and interpretative invention, it’s darkish vision of the Fairy world (with superimposition and ballet interjections giving it a darkly surreal touch) as influential as it’s haphazard approach to place and setting. Its comic performances come alive with real energy, devoid of the more stately approach from others. Above all, MND feels like an actual interpretation of its source material, rather than just a respectful staging – and its influence played out over decades of productions to come. Overlooked for too long, it’s a fine and daring piece of film Shakespeare, far better than it has a right to be.