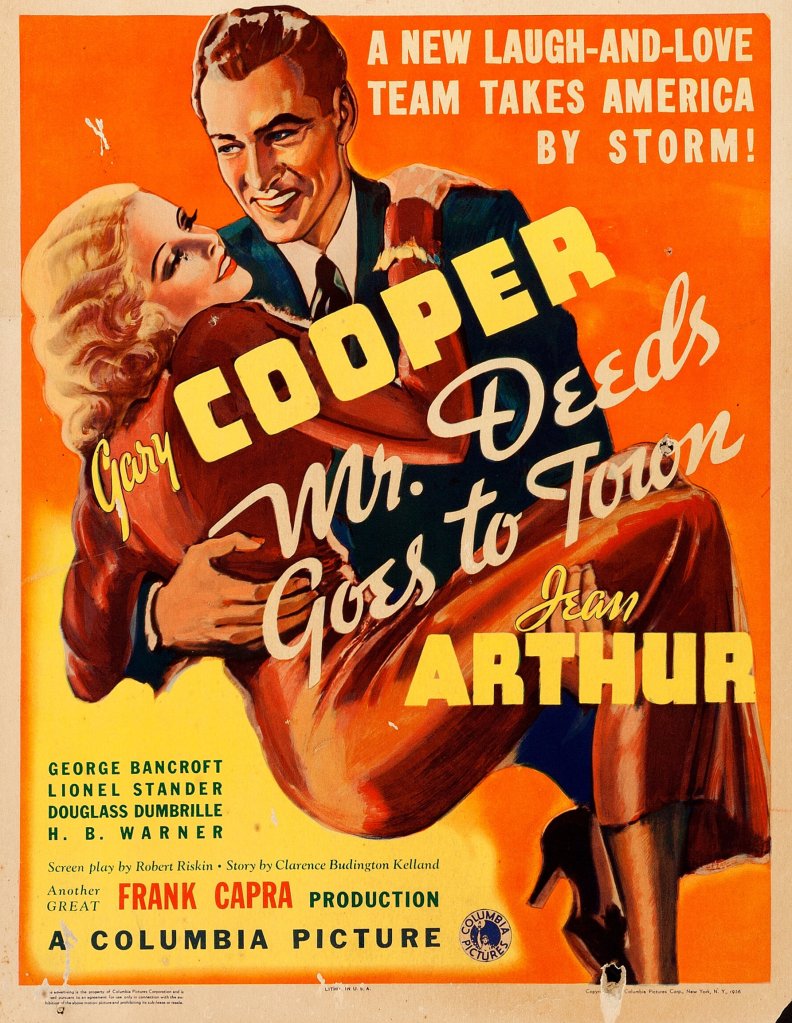

Capra’s brilliant comedy lays out his world version – and is extremely entertaining to boot

Director: Frank Capra

Cast: Gary Cooper (Longfellow Deeds), Jean Arthur (Babe Bennett), George Bancroft (McWade), Lionel Stander (Cornelius Cobb), Douglass Dumbrille (John Cedar), Raymond Walburn (Walter), HB Warner (Judge May), Ruth Donnelly (Mabel Dawson), Walter Catlett (Morrow), John Wray (Farmer)

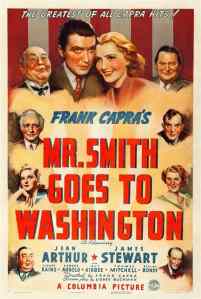

If any film first set out what we think of today as ‘Capraesque’ it might well be Mr Deeds Goes to Town. This was the film where so many of the elements we associate Capra – the honest little guy and his small-town, homespun American values against the selfish, two-faced, disingenuousness of the elites – really came into focus. Mr Deeds Goes to Town develops these ideas with a crisp, sharp comic wit, with Capra’s reassuringly liberal-conservative message delivered to perfect, audience-winning effect. It led to the even-better Mr Smith Goes to Washington and the template for every film which celebrates the little guy asking ‘why’ things have to be done this way.

Longfellow Deeds (Gary Cooper) is just your-average-Joe from small-town Mandrake Falls in Vermont who suddenly finds that he has inherited the unheard-of sum of $20million from a recently deceased uncle. His uncle’s assorted lawyers, led by suavely corrupt John Cedar (Douglass Drumbille) expect the naïve Deeds will happily allow them to continue riding the gravy train they’ve enjoyed for years. However, Deeds proves to have a mind of his own, refusing to kowtow to opportunists.

However, Deeds has an Achilles heel: he’s fallen hard for Babe Bennett (Jean Arthur), who he believes to be an out-of-work office girl but is in fact a star reporter, spinning the stories she picks up from their dates into articles about Deed that make him a laughing stock (the ‘Cinderella Man’). When Deeds discovers the truth – and is simultaneously threatened by Cedar with institutionalisation over his plans to give away his fortune to help the poor – he’s flung into a desperate court case to establish his sanity. Will a heart-broken Deeds defend himself?

Mr Deeds, with a sparkling script from Riskin, captures Capra’s idea of true American values. Deeds is a softly-spoken, unfailingly honest, no-nonsense type who won’t waste a minute on flattery and forlock-tugging and respects hard-work and plain, simple decency. He’s an independent spirit: be that playing the tuba, sliding down the banisters of his grand home, jumping on board fire trucks to help out or sweetly scribbling limericks, he’s as endearingly enthusiastic as he is lacking in patience for pretension.

He also proves an honest man is no fool, but a shrewd judge of character – expertly recognising a lawyer who turns up pushing for his uncle’s ‘common law wife’ to take a share of his fortune is an ambulance-chasing crook – and he’s no push-over or empty suit (made the chair of his uncle’s Opera board, he shocks the rest by actually proceeding to chair the meeting and make decisions). He’s the sort of humble-stock, common-roots, middle-class hero without any sense of snobbery or self-importance, just like his hero President Grant, judging people on their merits not their finery.

It is, in short, a near perfect role for Gary Cooper, at the absolute top-of-his game here: funny, charming and hugely endearing. Cooper can also convincingly back-up Deeds’ affability with a (literal) fist when pushed too far. Cooper is an expert at preventing an otherwise almost-too-good-to-be-true character from becoming grating or irritating. He’s also extremely touching when called upon – his giddy, bed-rolling phone call to Jean Arthur’s Babe is as sweet as his broken edge-of-tears sadness when he discovers she’s been lying to him (I can think of very few 30s actors who would have been comfortable looking as emotionally vulnerable as Cooper does here).

But Capra’s world view was always more complex though than we think. It’s easy to see Mr Deeds as arguing we should re-direct our efforts to helping the poor and needy, and the greed and hypocrisy of the rich (the sort of snobs who mock Deeds to his face at the dinner table). That might be closer to screenwriter Robert Riskin’s views: but actually, Capra’s vision has more of an Edwardian paternalism to it. He sees Deeds’s destiny – once he renounces the wild living of suddenly being loaded – not be a Tony Benn style-radical but the sort of paternalistic benefactor of the deserving poor you might see in a cosy Downton Abbey-style costume-drama.

Because the people Deeds ends up helping share his view of the world, as one where hard-work and having the right attitude should lead to rewards (with the implicit message, that if you can’t succeed then, it’s your fault). Deeds is tugged out of his slowly forming playboy lifestyle by John Wray’s desperate farmer. Wray is at the heart of a genuinely affecting sequence, determined to cause Deeds harm (believing stories of him frittering away money on eccentric trifles) and ending it in shameful tears, accepting Deeds unasked-for help. Like this man, those Deeds helps have lost farms and land due to the depression, screwed by the games of the financial elites.

But Mr Deeds Goes to Town never once tries to suggest there is anything fundamentally wrong with this system – only some of the people who have risen to the top. And even then, it’s their personal greed and inverted snobbery that’s their crime, not the fundamentally unbalanced financial system. The main strawman for elite’s financial frippery is the Opera house committee Deeds chairs for: he can’t see the point of taking a loss on an art institution, essentially arguing it should focus more on commerce to earn its way – the sort of art view that it’s only good if loads of people pay for it (on that basis Avengers Endgame is the greatest film ever made).

It’s part of a criticism of snobbery that the homely, common-man, Deeds can’t abide: captured in the idea that enjoying the plays and books ordinary people don’t want to read is somehow proof of an elitist coldness that doesnt value ordinary people. There’s an inverted Conservative snobbery here.

Now, don’t get me wrong: there’s still a decent world-view in Capra at valuing hard working people who want to help themselves. In the big city where life is a “crazy competition for nothing”, it’s refreshing to have someone who doesn’t care about societies ins and outs society, but does care that hungry farmers have a sandwich to eat. But it’s also a more conservative, and safe message than people remember.

Saying all that, Mr Deeds is a hugely entertaining film. The romance between Cooper and Jean Arthur (absolutely in her element as the screwball femme fatale with a heart-of-gold) expertly mixes genuine sweetness with spark. The film’s Act Five trial scene is perfectly executed, a brilliant parade of snobs and slander leading to an inevitable final reel rebuttal from Cooper that the actor knocks out of the park. (It works so well, the whole structure would be largely repeated in Mr Smith with the twist that here Deeds doesn’t speak at all) There are a host of superb performances: Stander is perfect as the cynical hack who finds himself surprised at his own conscience, perfectly balanced by Drumbrille as the suave lawyer who has no conscience at all.

All of these elements come together to sublime effect in a film that is rich, entertaining and genuinely sweet – with a possibly career-best performance from Cooper (Again, it’s refreshing to see an alpha-male actor so willing to be vulnerable). Capra’s direction is sublime: dynamic, witty and providing constant visual and emotional interest. Its politics are more conservative and simplistic than at first appears, but as a setting-out of Capra’s mission statement for warmer, kinder, small-town American values of simplicity, plainness, honesty and decency it entertainingly puts forward as brilliant a case as Deeds does.