Very 80s comedy, full of rude gags and the glories of money still funny in many places

Director: John Landis

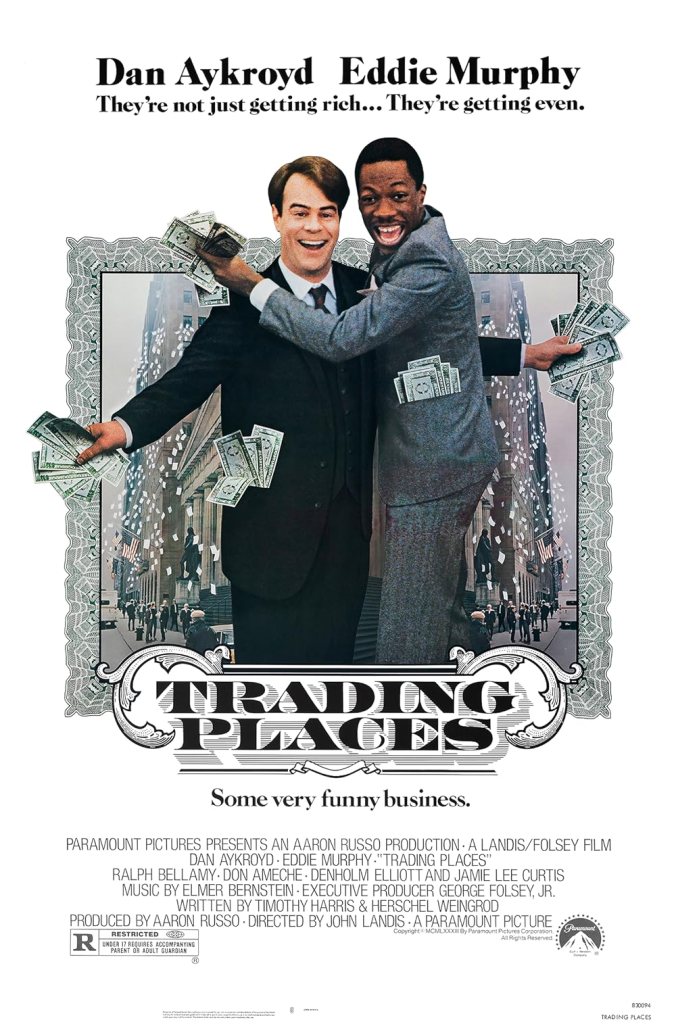

Cast: Dan Aykroyd (Louis Winthorpe III), Eddie Murphy (Billy Ray Valentine), Ralph Bellamy (Randolph Duke), Don Ameche (Mortimer Duke), Denholm Elliott (Coleman), Jamie Lee Curtis (Ophelia), Paul Gleason (Clarence Beeks), Kristin Holby (Penelope Witherspoon), Jim Belushi (Harvey)

Louis Winthorpe III (Dan Aykroyd) has it all. A house in Philadelphia, glamourous fiancée and high-flying job as Managing Director at Duke & Duke, the leading blue-chip commodities brokers. Billy Ray Valentine (Eddie Murphy) has nothing: penniless, homeless, hustling on the Philly streets. But is their fate due to nature or nurture? Finding that out is the subject of a bet between heartless Duke brothers Randolph (Ralph Bellamy) and Mortimer (Don Ameche). They turn both men’s lives upside-down by swopping their positions – Louis will be disgraced and left with nothing and Billy Ray will get his house and job. Will they fall or rise? And what will they do when they find out their lives are the Duke’s playthings?

Trading Places was one of the big box-office smashes of 1983, a film that changed the lives of virtually the whole cast. It showed the world Aykroyd could carry a comedy without partner Jim Belushi, gave a second career to Bellamy and Ameche, led Curtis to say the role “changed her life” from just a scream queen and, perhaps most of all, turned Murphy into a mega-star. It’s still witty, fast-paced and funny today, even if in places it’s not always aged well.

Landis takes a screwball approach, unsettling the lives of two contrasting people and then throwing them into an unlikely revenge partnership. Trading Places is very strong on the contrasting world of rich and poor. The wood-lined, club-bound world of the Dukes is carefully staged, paintings of financial and political grandees staring down from walls as assured, masters-of-the-universe easily sachet around posh clubs and squash clubs, to the sound of Elmer Bernstein’s Mozart-inspired score. By contrast, the rough, litter-lined squalor of Philadelphia’s poorer neighbourhoods is unflinchingly shown with, under the comedy, the suggestion life is cheap and everyone is for sale.

Of course, a lot of the ensuing laughs come from seeing a rich person who has only known comfort thrown into this life of a tramp and vice versa. Ackroyd’s Winthorpe bristles with disbelief at his situation and the rich man’s blithe assurance that (any moment) someone will say there has been a terrible mistake carries a lot of comic force. Meanwhile, Murphy’s fast-talking Billy Ray assumes he is the subject of an elaborate prank (or perverted sex game) as stuffs the pockets of his first tailored suit with knick-knacks around the house the Duke’s assure him is now his. Hustler Billy Ray turns out, of course, to be well-suited to the blue-collar hustle of financial trading. He also finds himself, much to his surprise, increasingly interested in the culture and artworks around him.

Under all this, Trading Places has a surprisingly negative view of rich and poor. Louis posh friends and shallow fiancée are all status-obsessed snobs who turn on him in minutes when he is framed for theft, embezzlement and drug trafficking. The servants in their posh clubs – all, interestingly, Black men in a quiet statement on race that you still wish the film could take somewhere more interesting – are treated as little better than speaking items of furniture and there is a singular lack of interest or concern for anyone outside their social bubble. Playing fair, every working-class character we see (apart from Curtis and Murphy) is lazy, grasping and shallow, ignoring Billy Ray until they can get something from him, at which point they fall over each other to snatch freebies from his house.

Trading Places is, in many ways, a very 80s screwball. Money is the aim and reward here. Trading Places has respect only for aspirational characters who save and invest their money. (Curtis’ prostitute is marked out as savvy and decent because she has invested nearly $42k from her work in a nest-egg). The film culminates in a financial scam (playing out on the trading floor of the World Trading Centre) designed to reward our heroes with wealth and punish the villains with poverty. For all the film stares at the reality of poverty and riches, the implications and injustices of wealth are ignored, with money ultimately framed as a vindication.

But then, Trading Places is just a comedy so perhaps that’s reading a bit too much in it. There is a frat-house energy to Trading Places under its elaborate framing and a lot of its gags come from a rude, smutty cheek that sometimes goes too far (not least a punchline involving a villain being repeatedly raped by a randy gorilla). Murphy’s energy – every scene has the crackle of improvised wildness to it – is certainly dynamic (this is probably his funniest and – eventually – most likeable role) and while Aykroyd is a stiffer comic presence, he makes an effective contrast with Murphy.

The real stars here though are the four supporting actors. Bellamy and Ameche seize the opportunity to play the villains of the piece with an experienced gusto, brilliantly funny in scene-stealing turns. Outwardly debonair, the seemingly cudily Bellamy and prickly Ameche superbly reveal the greed and casual cruelty of these two heartless Scrooges. Elliot is also extremely funny, and the most likeable character, as a kind butler just about disguising his loathing of the Dukes. Curtis’ vivacity and charm makes a lot of an under-written “hooker with a heart of a Gold” trope – like her co-stars she seizes her chance with a fun role.

Some of Trading Places has of course not aged well. Jokes with gay slurs pop up a little too frequently. While the Duke’s use of racist language makes sense (after all they are vile people who see Billy Ray as nothing but a curious toy), it’s more of a shock to hear our nominal hero Louis do the same. Murphy’s improvised sexual harassing of a woman on the streets (ending with him screaming “bitch!” after her when she walks off) doesn’t look good. Curtis twice exposes her breasts for no reason. The film’s closing heist involves Aykroyd blacking up and affecting a Jamaican accent.

But, dubious as some of this is now (and while you can argue times have changed, surely even then some people would have been unsettled by this sort of stuff framed for good-old-belly laughs), Trading Places is still funny enough to be a pleasure. And, with the performances of Bellamy, Ameche, Elliot and Curtis we have four very good actors providing a humanity and professionalism to ground two wilder comedians. It’s easy to see why this was a hit.