|

Liam Neeson is outstanding as Irish revolutionary leader Michael Collins |

Director: Neil Jordan

Cast: Liam Neeson (Michael Collins), Aidan Quinn (Harry Boland), Stephen Rea (Ned Broy), Alan Rickman (Eamon de Valera), Julia Roberts (Kitty Kiernan), Ian Hart (Joe O’Reilly), Brendan Gleeson (Liam Tobin), Sean McGinley (Smith), Gerard McSorley (Cathal Brugha), Owen O’Neill (Rory O’Connor), Charles Dance (Soames), Jonathan Rhys Meyers (Assassin), Ian McElhinney (Belfast cop)

Britain’s colonisation of Ireland left a poisonous historical legacy that blighted much of the twentieth century. The story of Irish independence, is also one of guerrilla and political brutality, civil war and terrible lost opportunities. Jordan’s biopic of Michael Collins is a study of the man who did more than any other to turn the IRA into an effective guerrilla fighting force – only to be consumed by the very same uncompromising ruthlessness he had set in motion. It’s a powerful and beautifully made film that seeks to explore just how and why violence and politics ended up hand-in-hand in Ireland for almost 100 years.

It opens with the 1916 Easter Uprising, an ignominious failure which the British managed to turn into a glorious one by executing rather than imprisoning its leadership. It’s one of many misjudgements in our occupation. It also the impetus for the young Michael Collins (Liam Neeson) to realise that playing by conventional military roles simply means defeat for the Irish time and again. Put simply, the IRA needs to stop trying to be a field army and instead become a guerrilla army, launching targeted hit-and-run terrorist attacks on the British. It’s a hugely successful campaign – despite the doubts of Sinn Fein leader Eamon de Valera (Alan Rickman), who favours more conventional conflict (“They call us murderers!” he cries, with some justification). But after the British agree a Treaty that divides Ireland, the IRA splinters into pro- and anti Treaty factions. Can Collins put the cork back in the bottle of violence, before the country tears itself apart?

Of course, anyone with a passing knowledge of history knows that he can’t. Hanging over the entire film is the knowledge that Collins’ new methods of political assassination, plainclothes soldiers, bombs and bullets in the middle of the night will eventually expand into the indiscriminate bombing and shooting that consumed Ireland for decades. Not that Collins will live to see it, as he was assassinated aged 31 attempting to negotiate an end to Civil War. What makes Collins such an engaging and intriguing figure is that he (or at least the version we see in this film) was a man forced into methods he knew were wrong, to achieve an end he knew was right.

Neeson is superb as the charismatic, blunt yet poetic Collins who is noble enough to know that training young men to quickly and efficiently commit murder is an ignoble legacy. Jordan’s film doesn’t condone Collins use of violence, but establishes why it was necessary. Playing by more conventional rules simply wasn’t going to work – and Ireland didn’t see why they had to wait for British politics to shift. Unlike, say Gandhi in India (and Michael Collins makes a dark companion piece with Attenborough’s Gandhi, two charismatic campaigners choosing radically different paths to independence), Collins believed Britain had to be forced to see holding Ireland wasn’t worth the blood sacrifice and emotional cost. (Jordan’s film is also clear that Britain’s hands were equally dirty, the British conducting their own counter-campaign of assassination and violence).

The tragedy that Jordan finds in all of this is that, when the British were gone, Ireland had become so used to dealing with political problems with violence that they couldn’t imagine solving their disagreements with anything else. Collins is in fact too successful: and the film demonstrates that in radicalising his followers, he’s unable to gearshift them towards compromise. His attempts to get Sinn Fein to accept a Treaty that offers a workable compromise (as opposed to an unwinnable full-scale war), leads to him becoming a victim of exactly the sort of insurgency he pioneered in the first place. To Jordan he is a man trapped in a world of his own making, unable to remove the gun from Irish politics.

Michael Collins makes some compromises with history – something that was bound to get it attacked when dealing with events of such earth-shattering controversy – but it always feel spiritually accurate. The British Black and Tans really were as brutal as they seem, and while they didn’t use an armoured car on the pitch at the “Bloody Sunday” massacre at Croke Park, they did shoot indiscriminately at the crowd and fire at the stadium from an armoured car outside causing 14 fatalities (including two children) and 80 serious injuries. Similarly, in the aftermath of Collin’s assassination of most of the British intelligence operation in Dublin, three IRA leaders were “killed while trying to escape” (even if these were different men than the one who suffers this fate in the film). Just as IRA killings in the street were swift and brutal, so interrogations in Dublin Castle could stretch way beyond what the Geneva Convention would suggest was acceptable.

Much of the first half of the film is structured in the style of an old-fashioned gangster film, with hits and street gangs. Plucky IRA under-dogs (and Neeson’s Collins is so charming, you immediately root for him), take-on the more hissable baddies in British intelligence (led first by a bullying Sean McGinley and then a suavely ruthless Charles Dance). But the romance slowly drains out of this as lifeless bodies hit the floor – and Jordan always gives the focus to the dead after they fall, regardless of their ‘side’. The film has an infectious momentum, which makes its final acts, with their air of tragedy, even more sad and moving. It’s all also quite beautifully shot by Chris Menges, the film bathed in some of the most luscious blues you’ll see.

While Michael Collins is more sympathetic to the Irish (as you would expect), it clearly shows the psychological damage of killing. Hesitant shooters become increasingly ruthless at the cost of their humanity. Collins spends a ‘dark night of the soul’ openly confessing that he hates what he is making young men do and knows it is morally wrong. In the end this explains why methods were chosen, but doesn’t praise them – just as it doesn’t outright condemn them, considering what the Irish were up against. It’s a difficult balance, but very well walked.

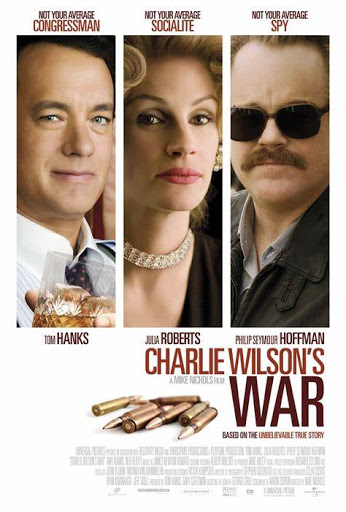

There are flaws. Excellent as Liam Neeson (at the time 15 years older than Collins was when he died) and Aidan Quinn as his number two Harry Boland are, the film’s insertion of a love triangle between them and Collin’s eventual fiancée Kitty Kiernan often descends into weaker “Hollywoodese”. It’s not helped by having Kitty played by an egregious Julia Roberts, who struggles gamely with the Irish accent, and who never transcends her star status.

Additionally, while the film has an excellent performance by Alan Rickman (in a pitch perfect vocal and physical impersonation) as Eamon de Valera, it also repositions de Valera as an antagonist. Although de Valera certainly was a prima donna who associated his interests and Ireland’s as being one and the same, the film implies that de Valera’s actions are motivated as much by jealousy as principle and lays most of the blame for the civil war on him. Not to mention implying de Valera’s complicity in Collins eventual death (a heavily disputed assertion, strongly denied by de Valera).

Michael Collins though is a thoughtful, complex and engaging film that brings a tumultuous period of history successfully to life. Jordan’s film manages to wrestle an enthusiastic admiration for Collins, with a questioning exploration of how his actions (however well motivated) led to a legacy of violence. But it doesn’t lose sight of how Collins was aware he was using wicked methods for a noble aim, or that his goal was to bring peace. Wonderfully acted by a great cast (every Irish actor alive seems to be in it), with Neeson sensational, it’s an essential watch for anyone interested in this period of history.