Michael Bond’s lovable bear makes an almost perfect screen-transition in this heart-warming tale

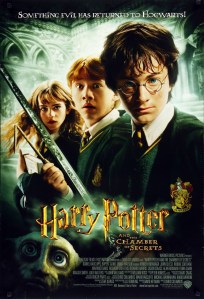

Director: Paul King

Cast: Ben Whishaw (Paddington Bear), Hugh Bonneville (Henry Brown), Sally Hawkins (Mary Brown), Madeleine Harris (Judy Brown), Samuel Joslin (Jonathan Brown), Julie Walters (Mrs Bird), Nicole Kidman (Millicent Clyde), Peter Capaldi (Mr Curry), Jim Broadbent (Samuel Gruber), Imelda Staunton (Aunt Lucy), Michael Gambon (Uncle Pastuzo), Tim Downie (Montgomery Clyde)

If there is one thing we need in troubled times, it’s kindness. Few characters are as overflowing with warmth and decency as Michael Bond’s Paddington Bear. First introduced in 1958, the lovable marmalade-consuming little bear all the way from darkest Peru is never anything less than kind and decent – even as the well-meaning bear gets himself into a string of catastrophes.

Paddington is one of the most universally beloved figures from post-War British culture – surely no surprise he was the perfect tea-party guest for that other beloved icon of the same period, the Queen. The pressure was on for a Paddington film – could it match the tone of the books? The answer was an over-whelming yes. Paddington is an endlessly heart-warming triumph, which it is impossible to watch without a warm glow building inside you, and a goofy smile on your face.

Explorer (Tim Downie) discovers a species of intelligent, marmalade-loving bears in darkest Peru. Forty years later, after a terrible earthquake, a young bear travels to find a new home in London. He meets the Brown family – overly cautious father Henry (Hugh Bonneville), caring Mary (Sally Hawkins) and their children Judy (Madeline Harris) and Jonathan (Samuel Joslin) – who take him into their home and name him Paddington after the train station where they found him (his bear name being unpronounceable). Paddington (Ben Whishaw) works hard to settle in with his new hosts – but danger looms from an ambitious Natural History Museum taxidermist (Nicole Kidman) who longs to make Paddington the centrepiece of her collection.

Directed with a great deal of unobtrusive flair by Paul King, Paddington is a truly endearing film about the triumph of opening your heart to strangers. The Brown family don’t realise it, but they are in need of a burst of kindness in their lives to help bring them together. They get it in spades with Paddington. The film captures perfectly the little bear’s personality. This is Paddington exactly as you remember him: polite, decent, kind and hilariously accident-prone. King’s film also gets the tone exactly right – there are no pop-culture references or rude gags (although there are a few subtle double-entendres of a sort) and the film is set in a timeless mix of 1950s London and today.

The film’s CGI Paddington is gorgeously designed – a wonderful rendering of the bear’s appearance tailored with more realistic fur, but still the same as the book– and perfectly voiced by Ben Whishaw. Whishaw was a late replacement – Colin Firth voluntarily withdrew, as he felt his voice was ill-matched to this naïve, gentle young bear – but his light and gentle tones convey all the warmth you need. It’s a superb performance, humane, kind and deeply funny, and so well suited you suddenly realise in your head Paddington always sounded like this.

King creates a series of gorgeously handled set-pieces to showcase Paddington’s possibilities for well-intentioned mayhem. On his first night in the Brown household, he duels with toothbrushes, mouthwash, toilet flushes and showers, culminating in flooding their bathroom with a swimming pool’s worth of water. He gets mummified in sellotape, slips up in the kitchen and causes several marmalade-sandwich involved disasters (most hilariously a marmalade baguette-pneumatic tube mix-up). But he always means well: a caper-filled set-piece through the London streets sees Paddington finally collide with a man he’s trying to return a dropped wallet too – allowing someone we’ve known all along to be a pickpocket to be apprehended by the police.

The Brown family’s home – already a beautifully designed dolls-house made real, with a tree blossom mural that changes to reflect the mood of the scene – comes to life with Paddington in it. (Watch how the colours of their clothing change depending on how much Paddington is part of the family or not). Mary (a wonderfully warm Sally Hawkins) is already eager for him to stay. Judy and Jonathan (superbly sparky performances from Madeline Harris and Samuel Joslin) are quickly won over by him. It’s only Mr Brown – a performance of perfectly judged fussy, pinickity, rule-bound caution and stuffiness by Hugh Bonneville which flourishes into something warmer – who is unsure. But then this is a man so obsessed with his risk analysis job, he prevents his children from doing anything (34% of all childhood accidents happen on the stairs!) and has forgotten how to have fun.

Watching Mr Brown slowly warm to Paddington is a huge part of the film’s charm and warmth. Who could imagine the man who tries to leave him at the train station (and urge his family not to catch the bear’s eye, muttering “stranger danger”) would later be dressing up as a Scottish cleaning woman to help him infiltrate the Geographer’s Guild building? (This sequence is a little comic physical and verbal tour-de-force Bonneville.) It’s a larger part of the film’s wider – and most rewarding – message: the importance of treating migrants to this country with respect and care.

The pro-migration message is throughout the film – and the film is a fabulous reminder to many of what we have gained from those who have come to this land from across the seas, from NHS staff to political leaders to entertainers. Paddington’s journey to London – in a small boat, then sneaking past customs – is all-too-familiar. Next door neighbour Mr Curry (a comically ingratiating Peter Capaldi) voices many of the “concerns” of anti-immigrant communities (let one bear in and who knows how many will follow?). Even Mr Brown voices worries about bears telling you sob stories to win your trust. The important message here is the value migrants bring us. A recurring calypso band reminds us of parallels with the Windrush generation. It’s not spoken but Jim Broadbent’s antique shop owner’s accent and memories of arriving on a train in London as a child clearly mark him as a Kindertransport child. Paddington has a subtle and truly important message for people: when we open our arms to people, we gain as much as they from the exchange.

Paddington throws in a few moments of darkness: the shock death of Uncle Patuszo is surprisingly affecting and Nicole Kidman’s taxidermist is possibly the scariest villain you’ll see in a kid’s film this side of the child catcher. But in some ways this enhances the warmth even further. By the film’s end you’ll feel your own life has been enriched by the small bear’s presence as much as the Brown’s has. We need him in times like this.