|

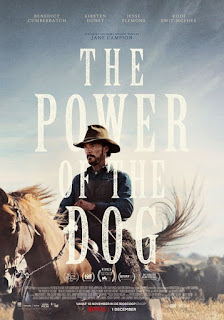

Benedict Cumberbatch rules his ranch with an iron fist in Jane Campion’s extraordinary The Power of the Dog |

Director: Jane Campion

Cast: Benedict Cumberbatch (Phil Burbank), Kirsten Dunst (Rose Gordon), Jesse Plemons (George Burbank), Kodi Smit-McPhee (Peter Gordon), Thomasin McKenzie (Lola), Genevieve Lemon (Mrs Lewis), Keith Carradine (Governor Edward), Frances Conroy (Old Lady), Peter Carroll (Old Gent)

At one point in The Power of the Dog, Phil Burbank, monstrously domineering Montana Rancher, stares out at his beloved hills. Where others see only rocks and peaks, Phil sees how (like a cloud) they form themselves into looking like a howling dog. Seeing things others do not is something Phil prides himself on. It’s also something The Power of the Dog excels out: it’s a continually genre- and tone-shifting film that starts as a gothic, du Maurier-like dance among the plains and ends as something so radically different, with such unexpected character shifts and revelations, you’ll be desperate to go back and watch it again and see if you can see the image of a dog among its rocks.

In Montana in 1925, two brothers run a ranch. George (Jesse Plemons) is polite, formal and quiet, seemingly under the thumb of his aggressively macho, bullying brother Phil (Benedict Cumberbatch). Phil is fully “hands-on” on the ranch, priding himself on being able to perform every task, from rope weaving to bull skinning, all of which he learned from his deceased mentor “Bronco” Henry. Things change though when George marries Rose (Kirsten Dunst). Phil takes an immediate dislike to Rose, engaging into a campaign of psychological bullying that drives Rose to drink. However, at the same time a strange bond develops between Phil and Rose’s student son Peter (Kodi Smit-McPhee) – is Phil’s interest in the boy part of a campaign to destroy Rose or are there other forces at work?

Campion’s film (her first in over ten years) is a fascinating series of narrative turns and genre shifts. It opens like a gothic Western. The ranch is a huge, isolated house surrounded by rolling fields and its own rules. Phil is an awe-inspiring, still-living Rebecca with Rose a Second Mrs de Winter having to share a bathroom with the perfect first wife. The psychological war Phil launches against Rose, like a hyper-masculine Mrs Danvers, seems at first to be heading towards a plot where we will see a vulnerable woman either crushed or fighting back. Then Campion shifts gears with incredible professional ease; the kaleidoscope shifts and suddenly our perceptions change along with the film’s genre, which becomes something strikingly different.

This all revolves around the character of Phil. Excellently played (way against type) by Benedict Cumberbatch, in a hugely complex performance, Phil at first seems an obvious character. A bully and alpha male who mocks George as “Fatso”, hurls homophobic slurs at Rose’s sensitive, artistic son and would-be doctor Pete, and treats his duties with such masculine reverence that the idea of wearing gloves to skin a cow or washing the dirt of his labour from him is anathema.

But look at Phil another way and you see his vulnerability. The opening scenes play as a torrent of abuse to George. But look again and you see this is a man desperately trying multiple angles to clumsily engage his brother in joint reminiscences. His emotional dependence on George is so great that they still share a single bedroom in their giant house (and even a bed in a guest house, like Morecambe and Wise) and he weeps on their first night apart. Despite his brutish appearance, his conversation is littered with classical and literary allusions (we discover later he is a Yale Classics graduate). His life is devoid of emotional and physical contact and he maintains a hidden retreat in the woods, a private den the only place we see him relax.

He’s a man clinging desperately to the past. At first it feels like he has never grown up, that he is still a boy at heart. But Campion slowly reveals his emotional bonds to his deceased mentor Bronco (whom he refers to almost constantly in conversation) to be far deeper and more complex than first anticipated. He treats Bronco’s remaining belongings with reverence, maintaining a shrine to him in the barn and cleaning his saddle with more tenderness and care than he feels able to show any human being. The depths of this relationship are crucial to understanding Phil’s character and the emotional barriers he has constructed. His gruff aggression hides a deep isolation and loneliness, feelings Campion explores with profound empathy in the film’s second half.

That doesn’t change the monstrousness of the bullying Phil enacts on Rose. Played with fragile timidity by Kirsten Dunst, Rose becomes so grimly aware of Phil’s loathing that is too paralysed by intimidation to even play Strauss on her newly purchased piano in front of George’s distinguished guests (Phil pointedly plays the music far better on his banjo and takes to whistling in in Rose’s presence) and later tips into alcoholic incoherence.

Despite Dunst’s strong performance, if the film has a flaw it is that we don’t quite invest in Rose enough to empathise fully with her emotional collapse. Both she and George (a fine performance of not-too-bright-decency from Plemons, in the least flashy role) disappear for stretches and play out parts of their relationship off camera, making it harder to bond with them (a bond the earlier part of the film needs). It perhaps might have been more effective to centre the film’s opening act on Rose rather than Phil, allowing us to relate to her better and feel her decline more.

Dunst however nails Rose’s growing fear, desperation and depression while her status as an unwelcome guest is constantly forced on her. Her panic only deepens with the return of her son Peter. This is where the film takes a series of unexpected shifts. To the surprise of all Phil offers to take the sensitive, quiet Pete under his wing: perhaps he’s impressed by Pete’s indifference to the homophobic abuse from the ranch-hands, perhaps he sees a chance to spiritually resurrect his mentor by playing the same role himself to Phil (pointedly, the film implies the younger Phil may not have been dissimilar from Pete). Either way, Campion’s film heads into its extraordinary and deeply impactful second half as an unsettling and uncertain personal drama between two men who seem totally different but may perhaps have more similarities than expected.

As Peter, Kodi Smit-McPhee gives a wonderfully judged performance of inscrutability and reserve. He’s an artistic boy who creates detailed paper flowers and keeps artistic scrapbooks, but can dissect animals without a flinch and snaps the neck of an injured rabbit with ease. He seems alternately devoted to his mother then queasily distant from her, calling her Rose and unsettled by her drunken inappropriateness. His motivations remain enigmatic, just as Phil’s motivations for befriending this isolated and very different boy could fall either way. Smit-McPhee and Cumberbatch are both extraordinarily good in the scenes between this unlikely partnership, and Campion’s artful film keeps us on our toes as to precisely what they want from this friendship. The result is haunting.

It leads into a stunning final act which demands we re-evaluate all we have seen and leaves such a lasting impression I was still re-living the film in my mind days later. Campion’s film is masterfully shot and carries a wonderful atmosphere of intimidation and unease, helped hugely by Johnny Greenwood’s brilliant score with its unsettling piano-inspired cadences. It reinvents itself constantly, Campion’s direction shifting tone and genre masterfully. It’s quite brilliantly acted and provides Cumberbatch in particular with an opportunity he seizes upon to slowly reveal depths of emotion and vulnerability an outwardly straight-forward monster. There won’t be many finer films released in 2021: and this will be a classic to sit alongside The Piano in Campion’s work.