Wayne’s historical epic is a mediocre labour-of-love that takes a very, very long time to get to its moments of interest

Director: John Wayne

Cast: John Wayne (Col Davy Crockett), Richard Widmark (Col. Jim Bowie), Laurence Harvey (Col. William Barrett Travis), Richard Boone (General Sam Houston), Frankie Avalon (Smitty), Patrick Wayne (Captain James Butler Bohham), Linda Cristal (Graciela), Joan O’Brien (Sue Dickinson), Chill Wills (Beekeeper), Joseph Calleira (Juan Seguin), Ken Curtis (Captain Almaron Dickinson), Carlos Arruza (Lt Reyes), Hank Worden (Parson)

John Wayne believed in America as a Shining City on a Hill and he wanted films that celebrated truth, justice and rugged perseverance. To him, what better story of fighting against all odds and to the bitter end for liberty, than the Battle of the Alamo? There, in 1836, a few hundred soldiers and volunteers from the Republic of Texas bravely stood before an army of over two thousand Mexicans to defend the Texas Revolution’s independence from Mexico. Wayne put his money where his mouth was, pouring millions of his own dollars into bringing the story to the screen. Furthermore, he’d direct and produce himself, convinced only he could protect his vision.

The end result isn’t quite the disaster the film has gained a reputation for being – nor is Wayne’s directorial efforts as useless as his detractors would like. But The Alamo is a long, long slog (almost three hours) towards about fifteen minutes of stirring action, filled with pages and pages of awkward speechifying, hammy acting and painfully unfunny comedy. While a bigger hit than people remember, Wayne lost almost every dime he put in (he said it was a fine investment) and even a muscular series of favour-call-ins that netted it seven Oscar nominations (including Best Picture!) couldn’t disguise that The Alamo is a thoroughly mediocre film that far outstays its welcome.

Wayne collaborated closely with his favourite writer, James Edward Grant. Both had a weakness for overwritten speeches and there is an awful lot of them in The Alamo’s opening half as we await the arrival of the Mexicans. Wayne gets several speeches about the glories of the American way such as (and this is cut down) “Republic. I like the sound of the word…Some words can give a feeling that makes your heart warm. Republic is one of those words” or a musing on duty that takes up a solid five minutes (it’s ironic Widmark’s Bowie refers to Harvey’s Travis as a long-winded jackanapes, since Wayne’s Crockett has them both beat).

There is only so much portentous, middle-distance-starring talk one can take before you start twitching in your seat, even for the most pro-Republican viewer. With complete creative control, there was no one to tell Wayne to pick up the pace and trim down these scenes. So enamoured was Wayne with Grant’s dialogue, whole scenes are taken up with the Cinemascope camera sitting gently in rooms watching the actors pontificate about politics, strategy and duty at such inordinate length you long for the Mexicans to damn well hurry up.

For a film as long as this, there is an awful lot of padding. The first hour shoe-horns in an immensely tedious romantic sub-plot for the increasingly-long-in-the-tooth Wayne (who had been playing veterans for almost 15 years by now) with Linda Cristal’s flamenco-dancing Mexican. We know she’s a hell of a dancer, since we get several showcases for her toe-tapping skills as Crockett’s Tennessee volunteers wile away the evenings. There is a sexless lack of chemistry between Wayne and Cristel, re-enforced by Crockett’s gentleman-like rescuing of Cristel from a lecherous officer, and the whole presence of this sub-plot feels as like a box-ticking exercise to appeal to as many viewers as possible as does the casting of young heart-throb Frankie Avalon in a key supporting role.

This is still preferable to the rather lamentable comic relief from a host of Wayne’s old muckers, playing a collection of Good Old Boy Tennesse volunteers. These jokers swop wise-cracks, prat-falls, good-natured fisticuffs, but (inevitably) also drip with honour and decency. Chief among them is Chill Wills as Beekeeper, a scenery-chewing performance of competent comic timing that inexplicably garnered Wills an Oscar nomination. Wills made real history with an outrageously tacky campaign for the golden man, shamelessly publicly pleading for votes and including a full-page Variety advert (‘The cast of The Alamo are praying harder than the real Texans prayed for their lives in the Alamo for Chill Wills to win!’) that even Wayne denounced as tasteless.

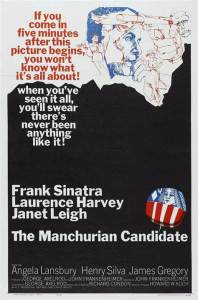

Wayne believed the real Oscar nominee should have been Laurence Harvey as ram-rod stickler-for-form Colonel Travis, commander of The Alamo. He’s probably right (if you were going to honour anyone here), as Harvey’s abrasive style and stiff formality was a good fit for the role and he turns the brave-but-hard-to-like Travis into the most interesting character. He’s more interesting than Widmark’s rough-and-ready Bowie, who looks uncomfortable: he would have been better casting as Crockett. That role went to Wayne, after investors said his presence in a lead role was essential for the box office (reluctant as Wayne was, he still cast himself in the most dynamic, largest role).

There are qualities in The Alamo – and they are largely squeezed into the final thirty minutes as the siege begins in earnest. This sequence is very well done, full of well-cut action and shot on an impressive scale. The money is certainly up-on-the-screen – The Alamo built a set only marginally smaller than the actual Alamo and recruited a cast of actors not too dissimilar from the size of the actual Mexican army. (The only nominations The Alamo deserved were related to production and sound design, both of which are impressive). The relentless final stand is undeniably exciting – whether it’s worth the long wait to get there is another question.

The Alamo largely avoids vilifying the Mexicans. Their commanders may be little more than extras, but Wayne’s was aware that in the Cold War, allies were crucial so the film is littered with praise for the bravery, courage and honour of the Mexicans as battle rages (‘Even as I killed ‘em, I was proud of ‘em’ one volunteer muses). However, in many ways, The Alamo is incredibly simplistic and naïve about American history – especially the ‘original sin’ of slavery, the banning of which in Mexico was one of the main reasons for the Texans revolt. It’s hard not to feel it’s a bit rich for Wayne to make a big speech about freedom, when Crockett and co were literally laying down their lives for the Texan Republic’s right to keep slaves. The only slave in the film is so overwhelmingly happy with Bowie, he literally refuses his freedom and lays down his life to protect his master.

But then that’s because The Alamo is a proud piece of propaganda, celebrating a rose-tinted view of American History that avoids complexity and celebrates everyone as heroes. It’s not the disaster you might have heard about. It has its moments. But its still a dull, tedious trek.