|

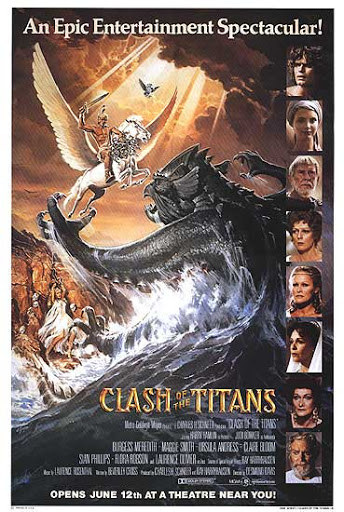

Harry Hamlin takes on monsters in Clash of the Titans |

Director: Desmond Davis

Cast: Harry Hamlin (Perseus), Judi Bowker (Andromeda), Burgess Meredith (Ammon), Maggie Smith (Thetis), Sian Phillips (Cassiopeia), Claire Bloom (Hera), Ursula Andress (Aphrodite), Laurence Olivier (Zeus), Susan Fleetwood (Athena), Tim Pigott-Smith (Thallo), Jack Gwillim (Poseidon), Neil McCarthy (Calibos), Donald Houston (Acrisius), Flora Robson, Freda Jackson, Anna Manahan (Stygian Witches)

It’s almost impossible not to have a soft spot in your heart for Ray Harryhausen’s stop-motion magic. The best of Harryhausen – and for me surely that’s his superb Jason and the Argonauts – has a magic that few other films can match. A magic born of awe at the technical skill and patience needed to bring it to the screen and the boundless imagination behind them. For all that they are no more real than the CGI of today, there is an emotional connection you can form with watching something where you know each frame was painstakingly hand-made, that you can’t quite feel for the scope of a computer-born Marvel world. Clash of the Titans was the last hurrah for Harryhausen. It’s far from perfect, and even in 1981 it looked dated and almost a relic from another era – but it still carries enough entertainment value.

We’re back in the mythology of ancient Greece. As a boy, Perseus (Harry Hamlin) and his mother are sent out to sea to drown by his Grandfather King Acrisius of Argos (Donald Houston), jealous of her love from Perseus’ father, the God Zeus (Laurence Olivier). Zeus orders Argos destroyed by the Titan sea monster the Kraken. Years later Princess Andromeda (Judi Bowker) of Joppa is due to marry Calibos (Neil McCarthy), son of the Goddess Thetis (Maggie Smith). But Calibos is cursed by Zeus, turned into a monster for his crimes. Andromeda is cursed by Thetis to only marry a man who can answer a riddle (set every night by Calibos). Perseus – using gifts from Zeus – discovers the answer to the riddle, confronts Calibos, cuts off his hand and is set to marry Andromeda.

But when Andromeda’s mother Cassiopeia (Sian Phillips) claims her daughter is more beautiful than any of the Gods, Thetis condemns the Andromeda to be consumed by the Kraken, or the city to be destroyed. To stop this, Perseus – with the quiet help of Zeus and his winged horse Pegasus – must travel across Greece to obtain the head of Medusa, who turns all who look upon her to stone.

Well, in case you were in any doubts (and I really struggled to write those last couple of paragraphs), one of Clash of the Titans main faults is that it’s plot is a mess (a combination of several Greek myths into one story) and lacks either a clear narrative thrust or a clear villain. It’s without focus, flabby and has so many sub-clauses in its structure, you either need to concentrate or just switch off and take it on a scene-by-scene basis. It’s summed up by the meaningless title which – for all Flora Robson’s Stygian witch shrieks “a titan against a titan!” mid-way through the film – barely relates to the plot.

The film also suffers from an over-abundance of characters (Gods, Kings, warriors, monsters) many of them only vaguely outlined. But with so much going on (and so much plot to cover in the slight running time) it all pulls focus from our two leads. Harry Hamlin’s Perseus is a dull, uncharismatic figure who it’s hard to get interested in. Judi Bowker fares a little better as Andromeda, but her brief moments of proactivity are only byways before she becomes a damsel in distress, chained to a rock. Neil McCarthy as nominal villain Calibos is undermined by only getting to play the character in close-up (in all other shots he’s all too obviously replaced by a tailed stop-motion monster), and in any case the character is barely given any decent motivation or background.

It doesn’t help these underpowered leads that there are a host of famous actors picking up pay cheques around them. Laurence Olivier made no secret of the fact that a large cheque (and only a week’s shooting time) was what bought him on board as Zeus (although the part is a good fit for his grandeur). Claire Bloom and Ursula Andress signed up for similar reasons. Maggie Smith (who was married to the screenwriter) seemingly did the film as a well-paid favour. Burgess Meredith repackages his role from Rocky as a poet turned advisor to Perseus. I will say Tim Pigott-Smith does a decent turn as the head of Joppa’s royal guard. But these are paper-thin characters, given what life they have by the actors rather than the script.

But Clash of the Titans is all about those Harryhausen set-pieces, with everything else just over-complicated filler to get us from place-to-place. Desmond Davis’ uninspired and flat direction doesn’t help, with the action too often presented in basic medium shot and frequently over-lit – a lighting set-up that doesn’t help to make the effects look particularly convincing. The film feels confusingly pitched, part a kids film, part an appeal to nostalgic adults. Neither seems to particularly work, and the film ends up looking rather uninspired.

This was the last hurrah for this sort of stop-motion. Star Wars had reset the table completely for adventure films like this. Clash of the Titans feels like a feeble attempt to address this challenge – right down to the irritating robotic owl Bubo, a clear rip-off of R2-D2 right down to his bouncing movement and dialogue of beeps. The film goes for making things as big as possible – the gigantic kraken, the huge scorpions – but everything in it looks a little tired.

Davis’ uninspired direction and the film’s flatness doesn’t help – or its general air of fusty, dusty oldness. If Jason and the Argonauts has all the charge and energy of a young man’s film (from its sharp direction, pacey plot, neatly drawn characters and Herrmann’s score), this really feels like a middle-aged Dad trying to be hip. The Kraken’s destruction of Argos seems to consist of little more than a few toppling pillars. The beast is slow, cumbersome and takes forever to do anything. An extended sequence where our heroes fight a two-headed dog is both dull and laughable. The only classic piece of stop-motion here is Medusa. Surely no coincidence that this is the most atmospherically shot sequence, with lighting that helps to hide the joins between stop-motion and reality in a way the rest of the film ruthlessly exposes.

Clash of the Titans is a film you can feel a nostalgia for – but really it’s actually rather naff. It’s badly plotted – surely the story could have been told in a cleaner way than this confused mess. Too many actors either phone it in, or fail to deliver the charisma needed (Todd Armstrong in Jason is no Olivier, but at least he had a matinee idol robustness Hamlin lacks). It’s limply directed. Worst of all, too much of the stop-motion looks a little silly – the film failing to cover up the cracks and too frequently exposing the joins rather than disguising them. Show this one to someone first, and you’ll never get them back to watch the best of Harryhausen. While I always enjoy it – for nostalgia if nothing else – its a cult classic, but no classic.