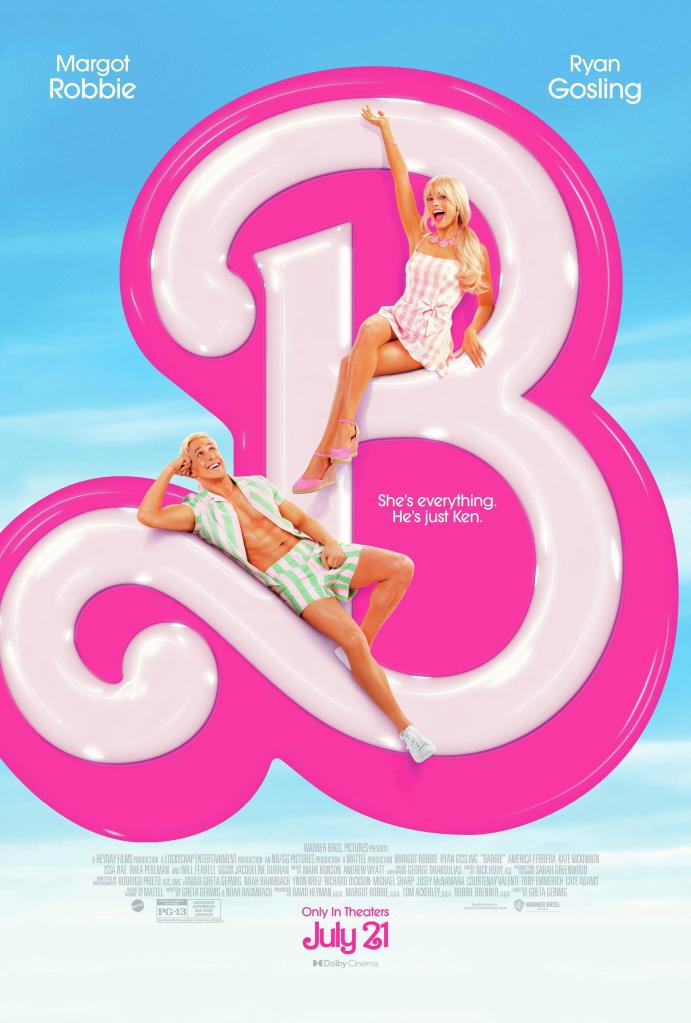

Fabulously pink comedy with serious – and very earnest – things to say on sexism and gender

Director: Greta Gerwig

Cast: Margot Robbie (Barbie), Ryan Gosling (Ken), America Ferrera (Gloria), Will Ferrell (Mattel CEO), Ariana Greenblatt (Sasha), Kate McKinnon (Weird Barbie), Issa Rae (President Barbie), Alexandria Shipp (Writer Barbie), Emma Mackey (Physicist Barbie), Hari Nef (Dr Barbie), Sharon Rooney (Lawyer Barbie), Kingsley Ben-Adir (Basketball Ken), Simu Liu (Tourist Ken), Ncuti Gatwa (Artist Ken), Michael Cera (Alan), Rhea Pearlman (Ruth Handler), Helen Mirren (Narrator)

Who knew that the film which sparked the most conversation in 2023 about the roles of men and women would be one launched by a toy company, with the goal of selling toys? Barbie feels a little like a project happily hijacked. In another world this could have been a straight-forward, Adventures of Barbie flick, designed only to get kids crying out for that Margot Robbie Barbie to be appearing under the Christmas tree. Instead, thanks to the team of Gerwig and Robbie, this is a self-reverential, witty, smart and highly engaging look at gender politics which also manages to be a fun, gag-filled evening out at the cinema.

Stereotypical Barbie (Margot Robbie) leads a blissful life in Barbie-Land, where every day is the best day ever. Every Barbie knows they’ve inspired change for the better for women in the Real World. Everything is perfect until one day Barbie starts thinking about Death. Before she knows it, she has flat feet, cellulite and a crisis of confidence. The only way to fix this? A journey to that Real World to meet with the child who’s playing with her. But Barbie and Ken (Ryan Gosling) find the Real World very different from what they expected: all women’s problems are not solved and Ken discovers The Patriarchy, a wonder he is determined to bring back with him to Barbie-Land. Can Barbie save Barbie-Land and help rebuild a relationship between moody teenager Sasha (Ariana Greenblatt) and her mother Gloria (America Ferrera) in the real world?

Barbie’s sharp playfulness mixes heartfelt messages on gender politics with the sort of joyful fish-out-of-water stuff beloved of family films where a naïve figure from our childhoods finds the real world a much harsher, more cynical place than they expected. Barbie’s expects our world to reflect of the female-dominated Barbie-Land is immediately exploded. Arriving in California, the reaction to an attractive woman roller-skating along a beach is remarkably different to what she’s used to. Wolf whistles, a parade of sexualised comments from construction workers (not a woman among them, to her shock) and a world where nearly all the top jobs are held by men.

Barbie addresses head-on whether a doll can really be an aspirational figure. In a surprisingly complex manner, Gerwig’s film looks at the pros and cons. Teenage Sasha doesn’t think Barbie has shown her world of possibilities, but instead sees her as a puppet of corporate America presenting a veneer of opportunity to women, while pushing them back into a box marked “pretty woman”. (This deadpan tirade provokes one the film’s many laugh-out loud lines as Barbie bemoans she can’t be a fascist as “I don’t control the railways!”.) Barbie may be able to do any job under the sun but this encourages attainment and also piles expectations on young women. If you can be almost anything at all, doesn’t that make it even the obligation to be something even more of a burden?

The real world is also a revelation – in a different way – to Ken. In our world, Ken discovers men (and possibly horses, Ken isn’t sure) rule though a marvellous thing called “the patriarchy”. Watching the Kens become infected by toxic masculinity, becoming high-fiveing bros who down beers, mansplain and call all the shots, is both funny and also a continuation of the film’s earnest exploration of gender politics. You can see, unpleasant as he becomes, that Ken might well want a piece of that action, coming from a world where men are so marginal they don’t even have homes (after all Mattel never made “Ken’s Dream House”). It’s also a neat gag that the other Barbies are easily brain-washed into accepting demeaning Stepfordish roles (dressed almost uniformly as French maids or in bikinis) because the confidence with which the Kens express their rightful place as masters-of-the-universe is literally mesmerising.

It’s also a neat part of Gerwig’s commentary here that the crucial factor to breaking out of this state is all about embracing the pressures of being expected to do it all: of being clever but not a know-it-all, ambitious but not a monster, raising a family but also having a career etc. If Barbie-Land in its beginning is a sort of vision of utopian feminism, then its salvation lies in accepting and embracing the struggle of marrying together a raft of contradictions and expectations. Sure, this isn’t exactly reimagining the wheel and its fairly easily digestible stuff – but it also rings true and you can’t argue with the connection its made with people.

All of which might make you think Barbie might be a po-faced political lecture. Fortunately, not the case when every point is filled with laugh-out-loud, irreverent humour expertly delivered by a cast clearly having the time of their lives. They are led by Margot Robbie, sensational in bringing to life a character who begins the film feeling like a doll made flesh and ends it as a three-dimensional character who embraces the contradictions of life. Robbie, who produced and set out much of the film’s agenda, is fabulous – funny, endearing, heartbreakingly vulnerable and extraordinarily sweet, mixing light comedy with genuine moments of pathos.

Equally good is Gosling playing the almost preternaturally stupid Ken with a winning sense of self-mockery, walking a brilliant line presenting a character who is (at times) the nominal villain but also a lost soul. Barbie also employs him and Robbie in some outstanding song-and-dance routines, deliciously performed and exquisitely funny. The other Barbies and Kens are uniformly excellent in their winning mix of initial shallowness and growing emotional depth while America Ferrera and Ariana Greenblatt are immensely winning as a mother and daughter overcoming a divide.

Barbie is also an explosion of delightful design and superb eye-for-detail, in its pitch-perfect recreation of a host of Barbie toys and props in real-life size, all thrown together with the perfect level of pink presentationalism. Drily narrated by an unseen Helen Mirren, every scene has a winning gag or laugh-inducing piece of business, especially when poking fun at the naïve optimism and artificiality of the Barbie world. Saying that, the film stumbles when it blurs the lines in the real world, which is half presented straight, half as a weirdly Wes-Andersonish oddity, particularly in the Mattel building and its corporate board, who are played as even more cartoonish than the actual toys populating Barbie-Land.

Barbie though generally works because it successfully mixes a heartfelt, earnest look at gender politics and the pressures on women with great gags, winning performances and a bouncy sense of off-the-wall fun that ensures nothing gets too serious. From its 2001 style opening, through its pink-led-primary colour settings, to its song-and-dance and larger-than-life-but-grounded performances, it’s a treat and in particular a triumph for its originator, producer and star Margot Robbie.

The history of the Tudors has been mined so often by film and theatre that there can hardly be any hidden stories left to tell, barely any twists that can be unveiled or reimaginings that haven’t already been imagined. Mary Queen of Scots certainly fails to find any new angles on its oh-so-familiar tale, and even its attempt to rework events and characters keeps banging its head on those damn, unchangeable real events that spoil the story it seems to want to tell.

The history of the Tudors has been mined so often by film and theatre that there can hardly be any hidden stories left to tell, barely any twists that can be unveiled or reimaginings that haven’t already been imagined. Mary Queen of Scots certainly fails to find any new angles on its oh-so-familiar tale, and even its attempt to rework events and characters keeps banging its head on those damn, unchangeable real events that spoil the story it seems to want to tell.