Farce, murder, mayhem and comic energy abounds in this sometimes try-hard but fun enough knockabout comedy

Director: Bryan Forbes

Cast: John Mills (Masterman Finsbury), Ralph Richardson (Joseph Finsbury), Michael Caine (Michael Finsbury), Peter Cook (Morris Finsbury), Dudley Moore (John Finsbury), Nanette Newman (Julia Finsbury), Tony Hancock (Inspector), Peter Sellers (Dr Pratt), Cicely Courtneidge (Major Martha), Wilfrid Lawson (Peacock), Thorley Walters (Patience), Irene Handl (Mrs Hackett)

Do you know what a tontine is? For those who don’t (come on, own up!) it’s basically an investment named after the Florentine banker Lorenzo di Tonti in 1653. Investors pay into a scheme which gives a regular income while accumulating interest on the initial capital. As the investors die off, the individual payouts increase until the final surviving investor claims the full ‘pot’ of cash. It’s essentially a lottery for being the last surviving investor. That’s ripe for two things: murder and farce.

We got dollops of the latter in this slap-stick, old-school farce loosely (very loosely) based on a Robert Louis Stevenson and Lloyd Osbourne novel. A Victorian tontine sees its members fall at regular intervals until there are only two survivors: estranged brothers, cantankerous Masterman (John Mills) and almost supernaturally tedious Joseph (Ralph Richardson). With Masterman pretending to be on his own deathbed to lure his brother out (to murder him), the blithely dotty Joseph is kept in health by his greedy nephews Morris (Peter Cook) and John (Dudley Finsbury). En route to see Masterman, a train accident leads to a series of farcical misunderstandings involving mis-identity, confusion and a dead body packed into a box and delivered to the wrong house.

Directed with an, at times, slightly too overtly zany bent by Bryan Forbes, The Wrong Box oscillates between being rather funny and trying too hard. It’s all too obvious to see the influence of the Oscar-winning Tom Jones in the film’s jaunty musical score and use of flowery-lined caption cards to announce events and locations. It’s also clear in the fast-paced, at times overblown, delivery of performances and dialogue, with its mix of improvisational humour and cheeky lines. Despite this though, The Wrong Box manages to be just about be fun enough (and it’s funnier than Tom Jones).

That’s probably because it’s not aspiring to be much more than a jaunt, an end-of-term treat in which a host of famous actors and comedians put on a show. Forbes might not have the inspired flair at comedy or the sort of timing this needs. But he’s got a nifty touch with dialogue and does a decent job of translating classic British theatre farce to the screen. The Wrong Box – even the title leans into this – is all about those classic farcical tropes of things being delivered to the wrong people because they have similar names, mistaken or misheard messages being passed on and people obliviously talking at cross purposes.

We get set-ups like Mills’ fake-bed-ridden old man trying multiple times to off Richardson’s bore, each attempt obliviously foiled by coincidence and accident. A body misidentified because its wearing someone else’s coat, then packed into a crate and delivered (to the wrong house) to disguise a death that hasn’t actually happened. Undertakers mistakenly taking away a man who has fainted at the foot of the stairs rather than a body in another room. All classic farce.

It’s not a surprise that experienced theatre actors emerge best. Richardson, in particular, is a delight as a man who has made such a study of trivia that he compulsively bores anyone he encounters. Fellow passengers on a train, a farmer who gives him a lift in his cart, attendees at a funeral – all of them glaze over in despair while Richardson’s Uncle Joseph, with monotonous eloquence, expounds mind-numbing trivia (including, at one point, in Swahili). He makes a fine contrast with Mills’ angry short-man, constantly fuming at a string of slights, real and imagined.

These two leads set the standard for the rest of the cast, a mix of comedians, theatre pros and star names. Peter Cook occasionally tries a little too hard as a bossy-boots determined to inherit the tontine – it’s remarkably that, even this early, Dudley Moore looks more relaxed in front of the camera (Moore’s later stardom would be inexplicable to the jealous Cook). Tony Hancock looks rather sadly like a rabbit-in-the-headlights as an inspector. Peter Sellers, not surprisingly, shows how it’s done: his two-scene cameo as a drunken doctor of loose morals, surrounded by cats and permanently sozzled is a master-class in low-key, rambling hilarity.

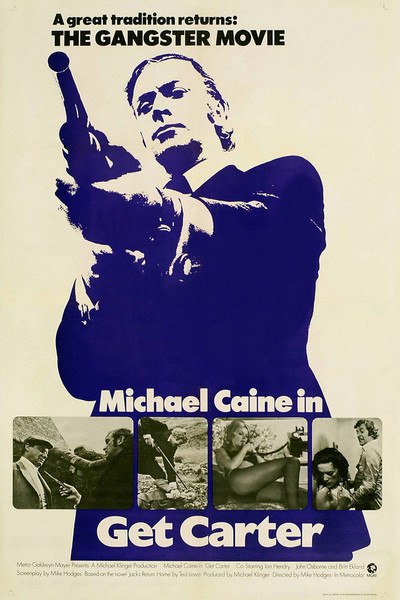

Michael Caine and Nanette Newman also acquit themselves very well. Throwing themselves into the spirit of things as our romantic leads – fulfilling the requirements of the genre by being both charming and sweet but also naïve and a little dim – they strike up a romance that manages to be both rather touching and also a neat parody of costume drama flirtation. Forbes shoots a rather nice scene where they breathlessly eye each other up, the camera cutting rapidly from exposed arms to facial features one after the other. Both are very funny, with Caine striking up a lovely double-act with Wilfrid Lawson as an almost incoherently drunk butler (Lawson’s finest hour since Pygmalion).

The film keeps its comic energy flowing well, with Forbes using a good mix of interiors and some attractive Bath locations (doubling for London). It’s also a film which – surprisingly since its written by a pair of Americans – really captures a sense of British eccentricity. I really enjoyed, in particular, the opening sequence that charts the deaths of the other members of the tontine – a parade of inept empire builders (soldiers, explorers, big game hunters) meting a series of surreal (often self-inflicted) deaths.

It probably does slightly outstay its welcome – 90 minutes would have been perfect. It’s a little too pleased with its semi-surreal set-up and stylistic flourishes – the floral on-screen captions definitely are far less funny than the films thinks. There is, at times, a little too much of the “isn’t this zany!” air about the film that can grate, with set-ups groaning with their desire to amuse (a late hearse chase scene falls into this) like a pub bore telling you a story in his self-proclaimed “inimical style”.

But at least The Wrong Box does make you laugh. And when that is all it is aiming to do, its hard not to have a soft spot for it.