Visconti’s realistic family epic simmers with the dangers of split loyalties, but is mixed on gender politics

Director: Luchino Visconti

Cast: Alain Delon (Rocco Parondi), Annie Girardot (Nadia), Renato Salvatori (Simone Parondi), Katina Paxinou (Rosaria Parondi), Roger Hanin (Duilio Morini), Spiros Focas (Vincenzo Parondi), Claudia Cardinale (Ginetta), Paolo Stoppa (Tonino Cerri), Max Cartier (Ciro Parondi), Rocco Vidolazzi (Luca Parondi, Alessandro Panaro (Franca), Suzy Delair (Luisa), Claudia Mori (Raddaella)

Visconti was born into a noble Milanese family: perhaps this left him with a foot in two camps. He could understand the progress and achievement of northern Italy in the post-war years, those booming industry towns which placed a premium on hard work, opportunity and social improvement. But he also felt great affinity with more traditional Italian bonds: loyalty to family, the self-sacrificing interdependency of those links, and the idea that any outsider is always a secondary consideration, no matter what. It’s those split loyalties that power Rocco and His Brothers.

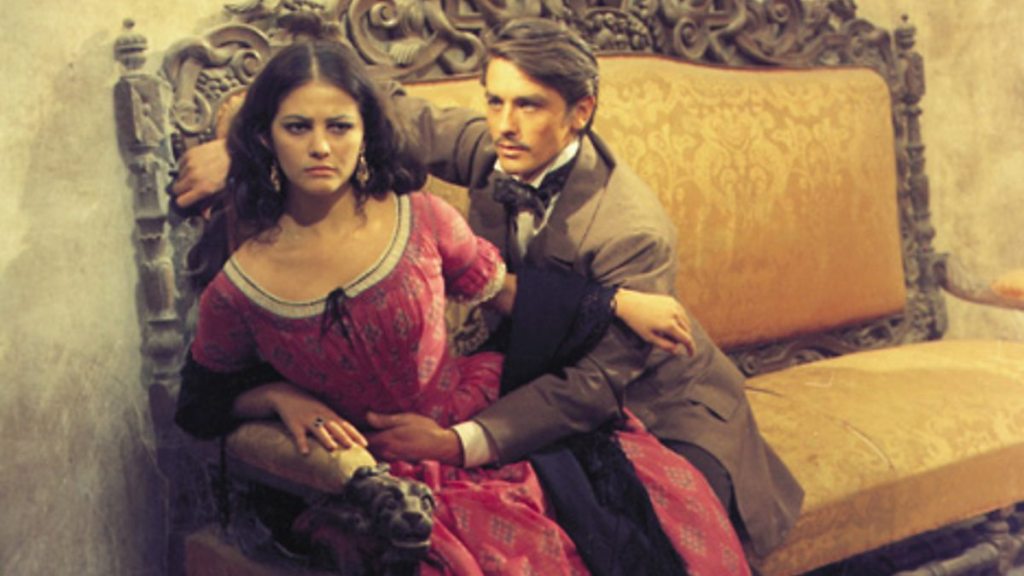

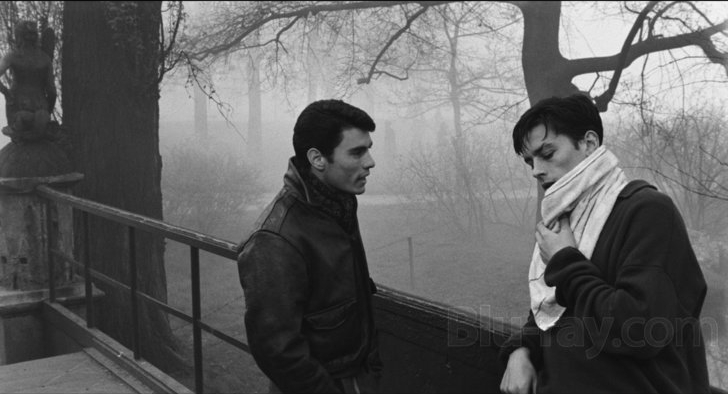

Rocco (Alain Delon) is one of five brothers, arriving in Milan from the foot of Italy looking for work with his mother Rosaria (Katina Paxinou). The hope of the family is second brother Simone (Renato Salvatori), a sparky pugilist destined for a career as a boxing great. But Simone can’t settle in Milan, too tempted by the opportunities he finds for larceny and alcohol. He falls in love with a prostitute, Nadia (Annie Girardot), until she rejects him and then he drifts ever downwards. Rocco, always putting family first, inherits his place first as a boxer than as Nadia’s lover. Problem is, Simone is not happy at being replaced, and the three head into a clash that will see Nadia become a victim in the twisted, oppressive, family-dominated loyalty between the two brothers.

Rocco and His Brothers is a further extension of Visconti’s love of realism – but mixed with the sort of classical themes and literary influences that dominated his later period pieces, themselves in their stunning detail a continuation of his obsession with in-camera realism. Filmed in the streets of Milan, where you can feel the dirt and grit of the roads as much as the sweat and testosterone in the gym, it’s set in a series of run-down, overcrowded apartment blocks and dreary boxing gyms that you could in no way call romantic.

This ties in nicely with Visconti’s theme. Rocco and His Brothers is about the grinding momentum of historical change – and how it leaves people behind. In this case, it’s left Rocco and Simone as men-out-of-time. Both are used to a hierarchical family life, where your own needs are sacrificed to the good of the family and every woman is always second best to Momma. While their brother Ciro knuckles down and gains a diploma so he can get a good job in a factory, Simone drifts and Rocco bends over backwards to clean up the mess his brother leaves behind. Naturally, Simone and Rocco are the flawless apples of their mother’s eye, Ciro an overlooked nobody.

The film focuses heavily on the drama of these two. And if Visconti seems split on how he feels about the terrible, destructive mistakes they make, there is no doubting the relish of the drama he sees in how it plays out. Rocco, by making every effort to make right each of the mistakes his brother makes, essentially facilitates Simone’s collapse into alcoholism, criminality and prostitution. Simone flunks a boxing contract? Rocco will strap on the gloves and fulfil the debt. Simone steals from a shop? Rocco will leave his personal guarantee. Simone steals from a John? Rocco will pay for the damage.

Caught in the middle is Nadia, a woman who starts the film drawn to the masculine Simone but falls for the romantic, calm, soulful Rocco. Wonderfully embodied by Annie Girardot, for me Nadia is the real tragic figure at the heart of this story. Whether that is the case for Visconti I am not sure – I suspect Visconti feels a certain sympathy (maybe too much) for the lost soul of Simone. But Nadia is a good-time girl who wants more from life. Settling down to a decent job with Rocco would be perfect and he talks to her and treats her like no man her before. Attentive, caring, polite. He might be everything she’s dreaming off, after the rough, sexually demanding Simone.

Problem is Nadia is only ever going to be an after-thought for Rocco, if his brother is in trouble. Alain Delon’s Rocco is intense, decent, romantic – and wrong about almost everything. He has the soul of a poet, but the self-sacrificing zeal of a martyr. He clings, in a way that increasingly feels a desperate, terrible mistake, to a code of conduct and honour that died years ago – and certainly never travelled north with them to the Big City. When Simone lashes out at Nadia with an appalling cruelty and violence, making Rocco watch as he assaults her with his thuggish friends, Rocco’s conclusion is simple: Simone is so hurt he must need Nadia more than Rocco does. And it doesn’t matter what Nadia wants: bros literally trump hoes.

Rocco does what he has done all his life. He wants to live in the south, but the family needs him in the north. He wants to be a poet, but his brother needs him to be a boxer. He loves Nadia but convinces himself she will stabilise his brother (resentful but trapped, she won’t even try, with tragic consequences). All of Rocco’s efforts to keep his brother on the straight-and-narrow fail with devastating results. Naturally, his mother blames all Simone’s failures on Nadia, the woman forced into trying to build a home with this self-destructive bully. Rocco’s loyalty – he sends every penny of his earnings on military service home to his mother – is in some ways admirable, but in so many others destructive, out-dated indulgence.

And it does nothing for Simone. Superbly played by Renato Salvatori, he’s a hulk of flesh, surly, bitter but also vulnerable and self-loathing, perfectly charming when he wants to be – but increasingly doesn’t want to. His behaviour gets worse as he knows his brother is there as a safety net. It culminates in an act of violence that breaks the family apart: not least because Simone crosses a line that Ciro (the actual decent son, who Visconti gives precious little interest to) for one cannot cross and reports him to the police.

That final crime is filmed with a shocking, chilling naturalism by Visconti, horrific in its simplicity and intensity. But I find it troubling that Visconti’s core loyalties still seem to be with the out-of-place man who perpetrates this crime and his brother who protects him, rather than female victim. Rocco and His Brothers could do and say more to point up the appalling treatment of Nadia, or at least make clearer the morally unforgiveable treatment she receives from both brothers (she’d have done better disappearing from Milan after Simone’s attack and never coming back, not playing along with Rocco’s offensive belief that Simone’s assault was a sort of twisted act of love).

Saying that, this is a film of its time – perhaps too much so, as it sometimes feels dated, so bubbling over is it with a semi-Marxist view of history as a destructive force. But it’s shot with huge vigour – the boxing scenes are marvellous and their influence can be felt in Raging Bull – and it ends on a note of optimism. The film may have disregarded Ciro, but there he is at the end – happy in his choices, settled, making a success of his life. Rocco and Visconti may see the drama as being exclusively with the old-fashioned brothers, making their counterpoint a paper tiger, but it ends with him – and (I hope) a reflection that Ciro’s path may be duller and safer, but also nobler and right.