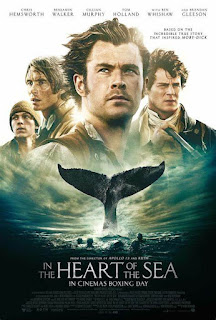

Hunger, desperation, the sea and a very big whale in this Moby Dick origins story

Director: Ron Howard

Cast: Chris Hemsworth (Owen Chase), Benjamin Walker (Captain George Pollard), Cillian Murphy (Matthew Joy), Tom Holland (Thomas Nickerson), Brendan Gleeson (Old Thomas Nickerson), Ben Whishaw (Herman Melville), Michele Fairley (Mrs Nickerson), Gary Beadle (William Bond), Frank Dillane (Owen Coffin), Charlotte Riley (Peggy Chase), Donald Sumpter (Paul Mason), Paul Anderson (Caleb Chappel), Joseph Mawle (Benjamin Lawrence), Edward Ashley (Barzillai Roy)

1820 and the world is run by oil. Not the sort you get out of the ground, but the sort you fish out of a whale’s corpse with a bucket. America is the leading exporter of whale oil and Nantucket is the centre of the industry. But it’s a dangerous business: as the crew of the Essex are about discover. Attacked by a whale, their ship sinks in the Pacific Ocean, thousands of miles from land. Passed-over first officer Owen Chase (Chris Hemsworth) and privileged captain George Pollard (Benjamin Walker) must set aside their differences to lead the survivors to safety. But starvation and desperation will lead those survivors to ever more desperate acts. All of this is told to Herman Melville (Ben Whishaw) by final living survivor Thomas Nickerson (Tom Holland and Brendan Gleeson), and it all sounds like a perfect inspiration for that Big Whaling Book Melville wants to write.

That Melville framing device is a good place to start when reviewing the many problems of In the Heart of the Sea, Ron Howard’s misfiring attempt at a survivalist epic. When we should be consumed by concern at whether these men survive, the film keeps trying to get us care as much about whether Melville will write a novel worthy of Hawthorne. The clunky prologue eats up a good sixth of the film, and we keep cutting back for Gleeson to tell us things the script isn’t deft enough to show us. Worse, it keeps ripping us way from the survivalist story that should be film’s heart.

Howard should know this: he directed one of the best survival-against-the-odds films ever in Apollo 13. Maybe the difference is that Apollo 13 is, at heart, a hopeful story. In the Heart of the Sea is about grimy sailors in a trade the film can’t find any sympathy for, eventually drawing lots in a long boat to see who is going to get killed and eaten by the others. It’s the sort of thing Werner Herzog would (pardon the metaphor) eat up for breakfast. For Howard, a fundamentally optimistic film-maker, its an ill fit. No wonder he wants to end the film with the triumph of Moby Dick.

In the Heart of the Sea is the rare instance of a film that is too short. The narration keeps skipping over time jumps in the first hour, that means we don’t get invested in the characters (most of whom are barely distinguished from each other, especially as beards and wasted bodies become the uniform). The sinking doesn’t take place until almost an hour in the film, meaning the time we spend with them lost in boats is a mere 40 minutes or so.

That is nowhere long enough for us to get a sense of either the monotonous time or the ravages hunger and desperation have made. Difficult as that stuff is to film – and I can appreciate its hard to make five men sitting, dying slowly, in a boat visually interesting – it means the film is asking us to make a big leap when it goes in five minutes from the men leaving a stop on an abandoned island to regretfully slicing one of their party up for dinner. We need to really understand how desperation has led to this point, but the film keeps jumping forward, as if its impatient to get to it.

Understanding is a general problem in the film. It can’t get past the fact that, today, we don’t see whaling (rightly so) as a sympathetic trade. But to these men, plunging a harpoon into a whale wasn’t an act of barbarous evil. It was more than even just making a living: it was a noble calling. Several times the film makes feeble attempts to push its characters towards moral epiphanies which seem jarringly out of chase (would Owen Chase, a hardy whaler with multiple kills, really hold his hand when confronted with a whale he thinks is trying to kill him?). Clumsy parallels are drawn between the heartless corporate oil industry of today, and the ‘suits’ back at Nantucket who only care about the bottom line.

Without accepting that, to these men, striving out into the ocean to bring back whale oil was as glorious a cause as landing on the moon, the film struggles to make most of the earlier part of the film interesting. Hard to sympathise with the characters, when the film is holding their profession at a sniffy distance. The film even radically changes the future career of its hero, Owen Chase, claiming he joined the merchant navy and never whaled again (not remotely true).

On top of this, Howard doesn’t manage to make the act of sailing feel as real or as compelling as, say, Peter Weir did in Master and Commander. Everything has a slightly unconvincing CGI sheen. Strange fish-eyed lenses keep popping up zooming in on specific features of pulleys and sails (is it meant to be like a whale’s eye view?). The film never manages to really communicate the tasks taking place or the risks they carry. There is a feeble personality clash between Pollard and Chase that fills much of the second act of the film, but is written and acted with a perfunctory predictability that never makes it interesting.

You can’t argue with the commitment of everyone involved. The cast noticeably wasted themselves down to portray these starving dying men. But it all adds up to not a lot. Chris Hemsworth gives a constrained performance as Chase – his chiselled Hollywood bulk looks hideously out of place – while Cillian Murphy makes the most impact among the rest as his luckless best friend. But the film’s main failure is Howard’s inability to make us really feel every moment of these men’s agonising suffering and to really understand the desperation that drove them to lengths no man should go to. Eventually that only makes it a surprisingly disengaging experience.