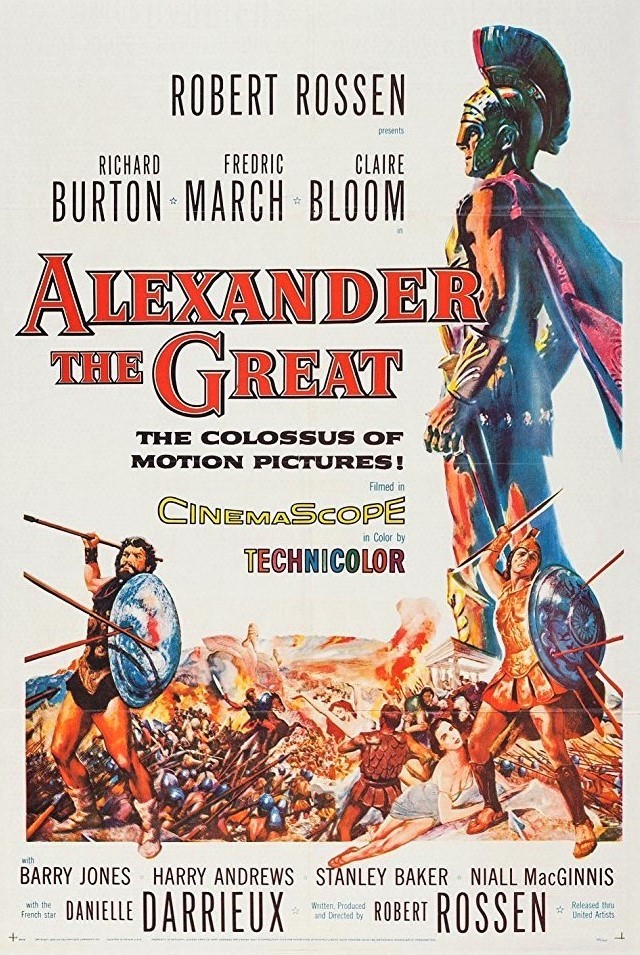

An odd epic, which both loathes its subject and also presents him as a golden-boy

Director: Robert Rossen

Cast: Richard Burton (Alexander the Great), Fredric March (Philip II), Claire Bloom (Barsine), Danielle Darrieux (Olympias), Barry Jones (Aristotle), Harry Andrews (Darius), Stanley Baker (Attalus), Niall MacGinnis (Parmenion), Peter Cushing (Memnon), Michael Hordern (Demosthenes), Marisa de Leza (Eurydice), Gustavo Rojo (Cleitus the Black), Peter Wyngarde (Pausanias), William Squire (Aeschenes)

No one in history achieved so much, so young as Alexander the Great. He conquered most of the known world before he was thirty and left a legend that generations of would-be emperors found almost impossible to live up to. He did all this, while remaining a fascinatingly enigmatic figure: either a visionary nation-builder or a drunken man of violence, depending on who you talk to. Alexander the Great, in its truncated two hours and twenty minutes (sliced down from Robert Rossen’s original three-hour plus) can only scratch the surface of his story and that’s all it does.

As the great man, Richard Burton flexes his mighty voice in a film that splits its focus roughly equally between the early days of Alexander and his troubled relationship with both his father Philip II (Fredric March) and his mother Olympias (Danielle Darrieux) and his own kingship and conquest of the known world until his early death. Surprisingly, perhaps because the world is so vast, it’s the first half of the film that’s the most interesting – perhaps because showing up the internecine dynastic squabbles between petulant royals are more up director and writer Rossen’s alley than global dominance.

Perhaps as well because it feels pretty clear Rossen doesn’t particularly seem to like Alexander. Over the course of the film, the pouting monarch will prove to have a monstrous ego (even as a teenager fighting Philip’s wars, he cockily re-names a sacked city after himself), ruthlessly slaughters opponents after battles, is prone to fits of rage, informs his followers with wild-eyes that he’s God himself, leads his army into the dried out hell of the deserts of the Middle East and turns (at best) a blind eye to his mother’s plans to assassinate his father and then murder his father’s second wife and baby son.

The film culminates in a shamed Alexander kicking the bucket more concerned with maintaining his legend for future generations than assuring any kind of future for his kingdom. But the sense of hubris destroying the great man is never quite captured. This is partly because the grand figure we are watching lacks any personal feelings or fear. He can’t seem to experience loss or grief and only understands negative events in terms of their impact on his reputation. And he never seems to truly learn from this – even when he harms friends, his regrets are based around the impact such action will have on how those around him see him. At the same time, Rossen can’t quite follow his heart and make a real iconoclastic epic meaning he instead leaves titbits here and there for the cinema-goer to hopefully pick up among the spectacle.

As such, Alexander is still pretty persistently framed as we expect a hero to be, with a rousing score backdropping Burton’s speeches and poses, even while the film seems deeply divided about whether this guy who conquered most of the known world and lay waste to Babylon was a good or bad thing. While acting half the time like a egomaniac tyrant, the film still carefully partially shifts blame for his character flaws onto his mother’s Lady Macbethesque influence (Darrieux does a good line in whispering insinuation) or Philip’s bombastic egotism (March, growling with impressive vigour).

Rossen has far more admiration for people like the fiercely principled Memnon (a fine Peter Cushing) who refuses to compromise only to be rewarded by a post-battle one-sided butchering from Alexander after his offer to surrender and spare the lives of his men is turned down. Even Michael Hordern’s Demosthenes comes across as a man of principle, certainly when compared to Alexander’s Athenian-of-choice Aristotle, interpretated here as a pompous windbag cheer-leader for dictators. Oddly even Harry Andrews (possibly, along with Niall MacGinnis’ wily Parmenion, the films finest performance) as Darius comes across as a man of surprising human doubt under his regal exterior. But, perhaps because of choppy-editing cutting down a complex story into just over two hours, Alexander the Great can’t resist framing its hero as a sun-kissed golden-boy, towering above everyone else in the film.

Watching Alexander the Great you get the feeling the film has effectively entombed him as a marble statue, so devoid is he of fundamental humanity. Perhaps this was Rossen’s solution to shooting a film about someone he seemed so devoid of human interest and sympathy for. There is a reason why Charlton Heston – the first choice for the role (can you imagine!) – called Alexander the Great “the easiest kind of picture to make badly”. Frequently Alexander the Great tips into a sort of sword-and-sandles camp made worse by how highly serious it takes itself. Not helped by Burton’s all-too-clear boredom with the part and contempt for the material, Alexander strikes poses and delivers speeches as if he’s been ripped straight out of Plutarch or a bust display in a museum.

Apart from rare moments – usually in the first half as he processes his complex feelings of love and loathing for his overbearing father – he is almost never allowed to be human. His friends – most notably his famed best-friend (and lover) Hephaestion – are reduced to a gang of largely wordless extras and only Claire Bloom’s Barsine is given any scope to talk to him as if he’s a man rather than just a myth. It gets a bit wearing after a while as you long for something human about the man you can cling onto.

It’s also a shame that Rossen seems uncomfortable with shooting the battle sequences. The battles of Granicus and a combined Issus-Gaugamela look rather like damp scuffles over shallow streams than some of the mightiest clashes of the Ancient world. Rossen communicates no visual sense of either strategy or scale (despite the bumper budget). Similarly, the grand sets look too theatrical and never quite as impressive as they should do, despite some fine painterly compositions. Rossen can never quite find a way to make his hundreds of extra seem like thousands and he falls back in the second half to communicating Alexander’s success through a tired combination of map montages, voiceover and repeated shots of men marching left to right and burning cities.

Alexander the Great is a deeply flawed epic. It’s neither swashbuckling fun that bowls you along, or a breath-taking piece of historical spectacle. Nor is it psychologically adept or insightful enough to show you something truly different about its hero. Instead, it tries to straddle both ways of thinking and ends up collapsing in the middle. If only Rossen had found his own Alexanderian solution to cutting this Gordian knot. Instead, the film just ends up a cut-about mess that fades from memory all too soon.