Effective journalistic investigation into a murder case turns into engaging courtroom melodrama

Director: Elia Kazan

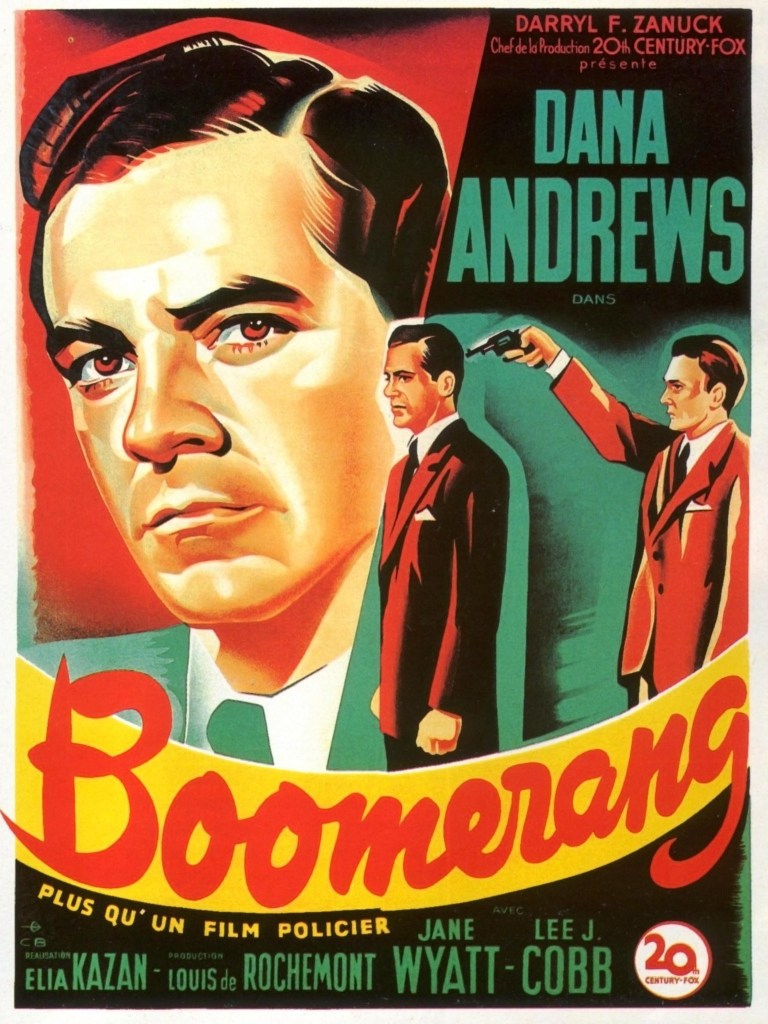

Cast: Dana Andrews (State’s Attorney Henry Harvey), Jane Wyatt (Madge Harvey), Lee J Cobb (Chief Harold Robinson), Cara Williams (Irene Nelson), Arthur Kennedy (John Waldron), Sam Levene (Dave Woods), Taylor Holmes (TM Wade), Robert Keith (‘Mac’ McCreery), Ed Begley (Paul Harris), Karl Malden (Lt White)

In Bridgeport, Connecticut, a popular priest is gunned down in the street, the killer escaping into the night. The police are baffled. The city turns against the reformist mayor’s administration. Then, after several weeks, there is a lead as twitchy ex-soldier John Waldron (Arthur Kennedy) is dragged in and, after hours-and-hours of interrogation without sleep, signs a confession. But who cares about small details like that, when everyone is sure the police has their man? But State’s Attorney Henry Harvey (Dana Andrews) has doubts – and no pressure from the public or officials will make him build a case against an innocent man.

Based on an actual 1924 murder case, Boomerang! is told with journalistic sharpness by Elia Kazan that smoothly moves from investigative into courtroom drama. Boomerang! was cited by Kazan as when he started to find his voice, establishing a style that would carry him to Oscar-winning success in On the Waterfront and beyond. Shot largely in location (though admittedly in a different Connecticut town than Bridgeport), it’s full of the immediacy of the streets, avoiding sets and forced studio locations. Kazan leans into the journalistic feel, with a voiceover explaining events and an earnest attempt throughout to make it feel like we are watching real events unfold.

It captures people going about their everyday lives: gossiping over laundry, strolling down streets, pounding typewriters in press rooms, gathering in church and shops. This is a film designed to convey a full sense of a real world. That goes as well for reflecting the investigation, which is full of the visceral pounding of pavements and hustling of suspects into police cars as well as the interrogations of the worn-down Waldron, taking place in an inhospitable room where never-ending questions means Waldron’s head has to be literally picked up to continue answering the questions.

The observational strengths of the film’s opening eventually moves into something more straight-forwardly melodramatic, but Kazan’s documentary restraint tries it best to not make this shift too jarring. As Harvey’s doubts grow, he becomes under increasing pressure from officialdom, principally from Ed Begley’s sweaty Paul Harris (who is too noticeably dodgy from the start for his villainy to be anything like a surprise). This is before a series of courtroom dynamics that hue towards the sort of fireworks you find in larger-than-life films than the journalistic reserve Boomerang! starts with.

Which isn’t to say that these courtroom dynamics are not very well-handled, especially by the under-rated Dana Andrews, who brings just the right amount of humanity and dignity to an otherwise stiff-on-paper character of a crusading, too-good-to-be-true attorney. Andrews delivers the courtroom speeches, and the detailed breakdown of the flaws in the police case, with a real quiet passion – just as he brings a nice degree of moral outrage to the bullying attempts to silence him.

Boomerang! provides several opportunities for compelling character actors, many of whom went on to work again for Kazan to great success. Lee J Cobb’s bulldog fierceness is perfect for put-upon police Captain Robinson who lets his determination to prove he can crack the case compromise his judgement. Cobb gives Robinson a powerful sense of authority – there is a wonderful scene where he faces down a would-be lynch mob with little more than growling disapproval. There is also a lovely moment, where he lifts the sleeping Waldron and carries him into his bed with all the care of a loving father. He’s well backed by Karl Malden as an eager-to-please inexperienced cop.

Arthur Kennedy produces one of his expert portraits in weakness as Waldron, an embittered veteran who has found peace offers little more than failure. While never losing track of what makes Waldron suspicious, Kennedy finds a neat line in vulnerability and fear keeps him sympathetic. Opposite him, Cara Williams explodes with righteous fury as a former girlfriend who believes herself wronged, eager to see Waldron condemned. It’s a more interesting role than any other female role in the film, although Jane Wyatt finds some engaging warmth in the dull role of Andrews’ loyal wife.

Boomerang! at heart is a film about the barrel being fine, aside from a few rotten apples. The crime takes place after the old machine politics system has been cast aside by new politicians, not beholden to the system, willing to introduce reforms. And, by and large, they are shown to really mean it – even if, at one point, some express the view that it doesn’t matter if Waldron is guilty or innocent, since winning means the reformists can remain in power. But all the real sins are collected in the hands of Begley’s character: even the police are absolved, despite the fact we watch them essentially brow-beat a man into confessing (a sergeant even suggesting they rough him up a bit to speed things along, which makes you wonder what the system was like for people are not veterans the police captain feels sorry for).

Boomerang! pulls any punches of really exploring systemic flaws, even while it covers an innocent man being bum-rushed into a trial. But then it puts complete faith in the idea that the same system will turn around and do its job by ensuring he is completely absolved – with the only danger from corrupt elected officials, not the blindness of a potential system. It’s a factor Kazan (to be fair) felt the film made too many compromises on – and he’s right. It might tell a scare story, but Boomerang! is fundamentally a reassuring film that is sure everything will turn out right in the end.