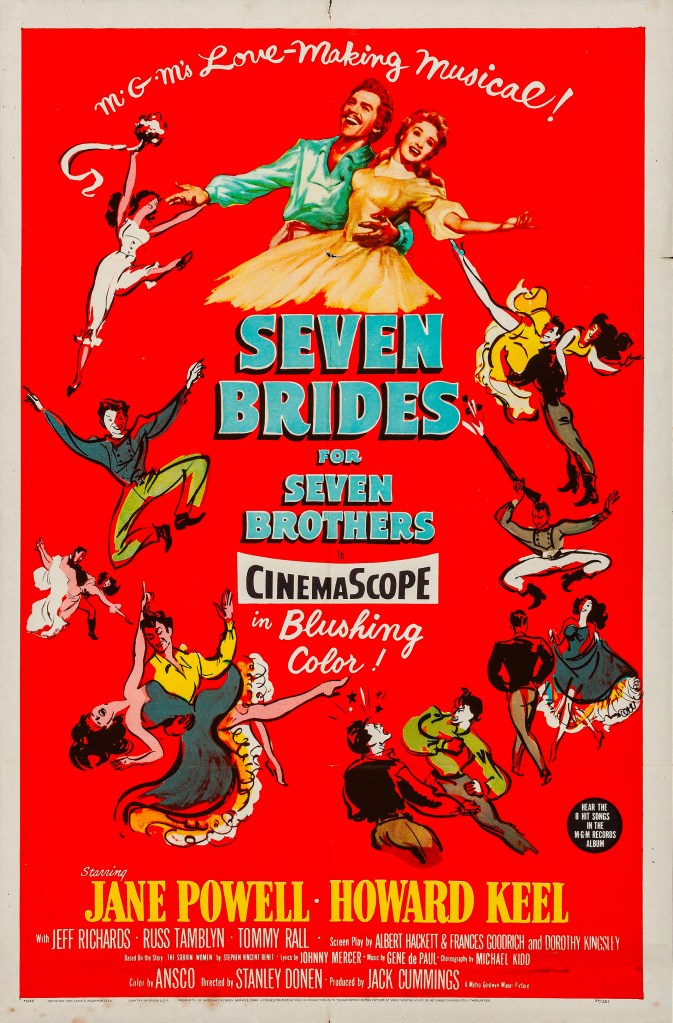

Gentle fun from more innocent times, in an impressively high-kicking Western musical

Director: Stanley Donen

Cast: Jane Powell (Milly), Howard Keel (Adam), Jeff Richards (Benjamin), Julie Newmar Dorcas), Matt Mattox (Caleb), Ruta Lee (Ruth), Marc Platt (Daniel), Norma Doggett (Martha), Jacques d’Amboise (Ephraim), Virginia Gibson (Liza), Tommy Rall (Frank), Betty Carr (Sarah), Russ Tamblyn (Gideon), Nancy Kilgas (Alice)

Glance at any list of odd things to adapt into a musical, and you might well find The Rape of the Sabine Women. You’ve got to admire the idea of shifting a Roman legend of horny menfolk grabbing armfuls of women from the Sabine tribe to carry them to Rome to make homes and babies, into… a primary-coloured, hi-kicking, cosy Western musical. Sure, parts of Seven Brides of Seven Brothers look rather awkward today but there is an innocent sense of good-fun (not to mention a sweet lack of sex in any frame) about the whole thing that still makes it rather charming today.

Out in Oregon in 1850, the Pontipee brothers are rough-living guys out in the sticks, who can’t imagine needing a woman in their lives, except maybe to cook and clean. That certainly seems to be what oldest brother, Adam (Howard Keel), has in mind when he marries Milly (Jane Powell). She is shocked to discover he sees her role solely in the kitchen and the laundry. Milly decides she’s not having this, pushing the brothers to clean up their home and acts. Much to their surprise, the brothers like clean living and fall in love with six more women in town (and they with them!). Shame they’re so inept at courtship they decide (much to Milly’s shock) the best way to get a wife is to grab a woman and bring them back home, just like those ‘sobbin’ women’ of yore.

You can see the trickier content there, but Stanley Donen’s film is so good-natured you can imagine its makers being baffled that anyone today could have an issue with it. We can address an elephant in the room: the kidnapping scenes – the Pontipee brothers throwing blankets over the women’s heads, chucking them over their shoulders and making for the hills – play uncomfortably today when framed for laughs. But these are men who, when they arrive home, are gosh-darn-it furious with themselves for not grabbing a priest so they could marry these women at once and immediately sleep in the cold barn to preserve the ladies’ dignities. Seven Brides for Seven Brothers is really a sort of fairy tale rather than a dance-filled Stockholm Syndrome drama, the beauties falling in love with the (not very beastly) beasts.

Take that mindset, and Seven Brides for Seven Brothers is gentle fun, more focused on its bright primary colours and superb dance sequences than any look at gender roles. Choreographed by Michael Kidd, the film is stuffed with imaginative showpieces showcasing the skills of its mostly professional-dancing cast. A pre-barn-raising dance turns into a competitive barn dance, with dancers throwing themselves into a myriad of possible positions, leaping over planks and swinging partners in wild circles (the film uses every inch of the Cinemascope framing – God alone knows what the 4:3 version Donen also had to shoot looks like). Every time the film kicks into dance mode, you are generally in for an impressively athletic treat.

The cast (except, noticeably Jeff Richards) are all strong dancers – or in the case of Russ Tamblyn so athletic it hardly matters – allowing Kidd to push the dance envelope. His choreography also conquers his initial concern: how believable would it be for rough-tough woodsmen like this to confidently trip the light fantastic at the drop of a hat? Its solved, in many cases, by using the sort of everyday jobs (like woodcutting in one single-take sequence) these boys would be doing as the framing device of the choreography. That and a wittily done sequence where Milly teaches her new brothers-in-law some basic dance steps only for them to find they actually enjoy kicking their heels.

Its one of several witty sequences, that serve to generally puncture for laughs the masculinity of this clan of brothers. Milly’s arrival, finding her new brothers-in-law are all strangers to the razor and the bath, then finds her tour of the house has to work around an on-going fight between these lads which her new husband all but ignores. By the time Milly is flipping over the dinner table after the brothers dive into her prepared meal with all the grace of a bunch of frat boys on a night out, you’re with her. In fact, Seven Brides could be a sort of Taming of the Shrew in reverse, where our heroine trains decency, politeness and basic interpersonal skills into the men. And, since Jane Powell’s firm-but-fair Milly is the most unfairly put-upon person in the film, we instantly side with her.

Instead, it’s Howard Keel’s (with his distinctive gloriously low voice) Adam who needs to be made to see sense: first to understand there is more to marriage than a servant-with-benefits, and secondly that other people’s feelings need consideration. Much of the drive for this change is Milly – the importance of her character being the main reason writer Dorothy Kingsley was recruited to bulk up her part from Albert Hackett and Frances Goodrich’s earlier drafts. Similarly, the seven brothers switch from punch-first braggarts to figures reminiscent of Snow White’s dwarfs in their eagerness to please Milly (even, during the barn-raising sequence, they politely back away from all provocations from the jealous townsmen until they are finally pushed too far by the townsmen’s rudeness to others).

In this framework, we are never in doubt that their brides-to-be are, in fact, not unhappy at being carried away by these men. There is no sense of danger in Seven Brides: no doubt that it’s not all going to turn out well. A large part of this gentle tone is due to Stanley Donen’s warm, witty direction. (Donen was heartbroken the budget wouldn’t stretch to Oregon location shooting, although the backdrops used throughout are hugely impressive). It generally looks like a film everyone had huge fun making – and that warmth, along with the brightly coloured shirt humble-pie-ness of it all, has meant it remains all jolly good fun today.