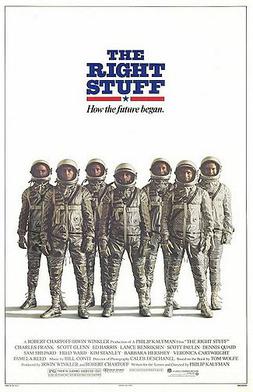

Patriotic heroism subtly retold as shrewd satire – no wonder the film bombed

Director: Philip Kaufman

Cast: Sam Shepard (Chuck Yeager), Scott Glenn (Alan Shepard), Ed Harris (John Glenn), Dennis Quaid (Gordon Cooper), Fred Ward (Gus Grissom), Barbara Hershey (Glennis Yeager), Kim Stanley (Pancho Barnes), Veronica Cartwright (Betty Grissom), Scott Paulin (Deke Slayton), Charles Frank (Scott Carpenter), Lance Henriksen (Wally Schirra), Donald Moffat (Lyndon B Johnson), Levon Helm (Jack Ridley), Mary Jo Deschanel (Annie Glenn), Scott Wilson (Scott Crossfield), Kathy Baker (Louise Shepard), David Clennon (Liaison man), Jeff Goldblum (Recruiter), Harry Shearer (Recruiter)

During the Cold War, the US and Russia had to fight with something – from proxy wars to chess, but most famously with Space: the competition to go further, faster and higher among the stars. The Right Stuff focuses on the Mercury Seven pilots at the centre of the US response to Soviet success including Alan Shepard (Scott Glenn), John Glenn (Ed Harris), Gus Grissom (Fred Ward) and Gordon Cooper (Dennis Quaid), a mix of the cocksure and the confident. But in a space programme where a monkey is an acceptable “pilot” for this human cannonball, do any of them have “the right stuff”? Could any of them match the skill of legendary test pilot Chuck Yeager (Sam Shepard) – one of the guys who scorned this astronaut programme for being “spam in a can”?

The Right Stuff, adapted from Tom Wolfe’s book, seemed destined to become a patriotic smash-hit. Despite its eight Oscar nominations (and four wins) it was, in fact, a catastrophic bomb. Perhaps that was because it subverted its patriotism so well. The Right Stuff is, in fact, a subtle, anti-heroic satire (told at huge length) masquerading as a patriotic yarn. It’s marketing avoided that meaning those most likely to enjoy didn’t go and see it, and those who went for that felt alienated. While largely respecting the astronauts, it suggests space race triumphalism was a sort of mass hysteria, with limited results, inflated into something mythic by political expediency, media spin and industrial might. Not the happy, flag-waving message Reaganite America expected or wanted.

Kaufman’s sympathy instead lies with an older, “truer” America. The Right Stuff is an intensely nostalgic film: but for a completely different time. It is in love with Frontier America, where men-were-men and the daring proved themselves in taming the frontier, in this case the sky itself. Our tamer is Chuck Yeager, played with a monosyllabic Gary-Cooper-charisma by Sam Shepard. Yeager is the last of the cowboys (even introduced riding a horse in the desert), taking to the skies like an old frontiersman hunting down that “demon” who lives at the sound barrier.

This is the sort of America The Right Stuff celebrates, and Yeager is the guy who has it. Unlike the Mercury programme, Yeager isn’t interested in showbiz and self-promotion (his reward for breaking the sound barrier? A free steak and a press embargo), just the quiet satisfaction of having done it. It’s the old, unflappable, quietly masculine confidence of a certain kind of American tradition and it’s totally out of step with the world the media is now celebrating with the astronauts. Instead, these effective passengers in the rocket will be hailed as the great pilots.

Kaufman’s film is a long, carefully disguised, quiet ridicule of many of the aspects of the Mercury programme. It’s conceived, in a darkened room, by a group of politicians so clumsy they can’t even work a projector. It’s head, Lyndon B Johnson (Donald Moffat on panto form) is a ludicrous figure, at one point reduced to an impotent tantrum in a car when he doesn’t get his way. The NASA recruiters are a comedy double act – Goldblum and Shearer sparking wonderfully off each other – who first suggest (in all seriousness) circus acrobats as pilots and then fail to identify Yuri Gargarin. The programme begins with a series of failed launches that travel tiny distances before exploding, culminating in one attempt ending with an impotent pop of the cap at the top of the rocket.

NASA is slightly ramshackle and clueless throughout. Far from the best and brightest, Kaufman is keen for us to remember that many of the scientists fought for the Germans in the war, that decisions were often made entirely based on what the Russians have just done, that the astronaut recruitment tests are a parade of bizarre physical tests because no one has a clue what to test for, and that the final seven selected aren’t even the best just the ones who persevered through the tests and (crucially) were small enough to fit in the capsule. That doesn’t stop the media – played by a San Francisco physical comedy troop – from turning them overnight from jobbing pilots to superstars.

The astronauts status is frequently punctured. Scott Glenn’s granite-faced Shepard is strapped into the cockpit for hours on his first flight, until finally he begs to pee (followed by a montage of coffee being slurped, hose pipes blasting and taps dripping) before being instructed to release his bladder into his suit, meaning he heads into space sitting in a puddle of his own piss. Dennis Quaid’s cocksure Cooper has an over-inflated idea of his skills and is prone to dumb, blow-hard statements (arriving at Yeager’s Air Force base he non-ironically states he’ll soon have his picture up on the deceased pilot’s memorial wall). Fred Ward’s Gus Grissom is a slightly sleazy chancer – controversially The Right Stuff presents him as panicking on re-entry from his first mission, blowing his hatch and sinking his ship, something he categorically denied (and was later proved not to have done).

Even John Glenn, played with a sincerity and decency by Ed Harris (if this had been a hit, Harris’ career of playing hard-heard would have been totally different), is subtly lampooned. So straight-laced he literally can’t swear (his attempt to say ‘fuck’ never gets past a strained Ffff), he’s introduced via a ludicrous TV quiz show and his square-jawed morals frequently tip into puritan self-importance. Undergoing physical tests, Kaufman even cuts from his grimacing face to a grinning chimp on the same test (and who will beat him into space). Compared to Yeager, who can correct a plane on a desperate nose dive and beat the skies into submission (and has the only outright heroic refrain in Bill Conti’s Oscar-winning score), none of them have that right stuff.

Do they get it? In a way: but their triumph is establishing their character, not their skills. Kaufman uses Yeager to point us towards this (his seal of approval is vital for the film): after Grissom’s debacle, he defends him in the bar and praises their courage in essentially sitting on top of a massive bomb.

Tellingly, the astronauts’ most courageous moment in the film isn’t in the cockpit at all: it’s Glenn supporting his stammering wife’s refusal to go on air with LBJ, despite the pressure from NASA bigwigs – and the other astronauts uniting in fury when Glenn is threatened with being dumped from the next flight. The others become more noble through maturing and casting aside fame’s temptations.

In a way they prove their spurs, even if Kaufman’s film makes clear none of them can match Yeager’s traditional values. The film ends with Yeager, maverick to the last, undertaking an unauthorised test flight in a desperate attempt to keep funding for his jet programme going. Even with this final flight – dressed in a bastardised version of a space suit – Yeager shows he’s not lost it, a man so undeniably superhuman in his American resilience that even a bit of fire won’t slow him down.

The Right Stuff celebrates Yeager, but he’s the B-story – and the film frames him as a forgotten figure, left behind by a world obsessed with the bright and shiny. The Right Stuff has to centre the astronauts but it doesn’t focus on the missions (which, apart from Glenn’s, barely receive any screen time – certainly not compared to the time given to Yeager’s flights) or the glory, only quietly implies there was a slight air of pointlessness about the whole thing – that the space race was perhaps just a dick-waggling competition between superpowers. It makes for interesting – if overlong – viewing, but as punch-the-air entertainment, no sir. No wonder it bombed.