A great Hollywood romance obscures darker, more sinister implications that its makers seem unaware of

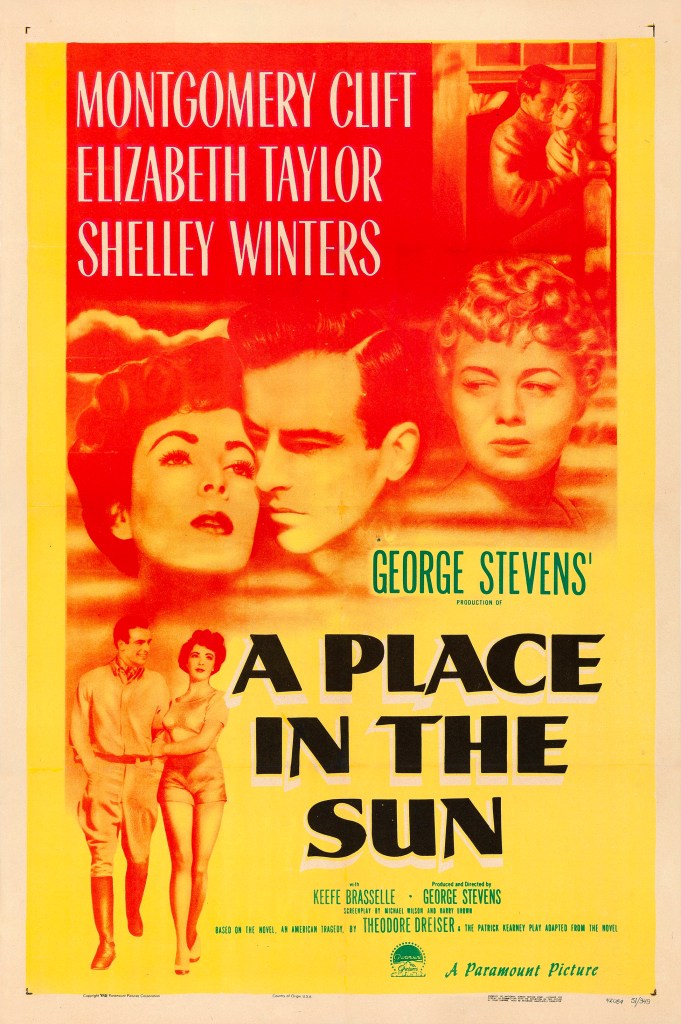

Director: George Stevens

Cast: Montgomery Clift (George Eastman), Elizabeth Taylor (Angela Vickers), Shelley Winters (Alice Tripp), Anne Revere (Hannah Eastman), Keefe Brasselle (Earl Eastman), Fred Clark (Bellows), Raymond Burr (DA Frank Marlowe), Herbert Hayes (Charles Eastman), Shepperd Strudwick (Tony Vickers), Frieda Inescort (Ann Vickers)

It’s based on Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy, but in some ways it feels like very British. After all, few American films are more aware of class than A Place in the Sun and there is something very British about a working-class man pressing his nose up against the window of the wealthy and wishing he could have a bit of that. In some ways, A Place in the Sun’s George Eastman is a more desperate version of Kind Heart’s and Coronets Louis desperate to be a D’Ascoynes or a murderous version of Room at the Top’s Joe Lampton not wanting his girlfriend to get in the way of wooing a better prospect. The most American thing about A Place in the Sun it is that what would be a black comedy or a bitter drama in Britain, becomes a tragic romance in George Steven’s hands.

George Eastman (Montgomery Clift) is from the black sheep working-class side of the Eastman clan, rather than the factory-owning elite side who live among the city’s hoi polloi. George is gifted an entry-level grunt job in the factory but works hard for progression. He absent-mindedly dates production line co-worker Alice (Shelley Winters), who thinks he’s the bee’s knees. Unfortunately for her, George meets Angela Vickers (Elizabeth Taylor), daughter of the wealthy Vickers family, and they fall passionately in love. Just as Alice announces she’s pregnant and asks when George will do the decent thing. Can George thread this needle, rid himself of Alice and marry the willing Angela? Perhaps with the help of the Eastman’s lake side house and Alice’s inability to swim?

You can see the roots of a cynical tale of opportunism and ambition there, but A Place in the Sun wants to become a luscious romance. It is shot with radiant beauty by William C. Mellor, bringing us sensually up-close with Clift and Taylor whose chemistry pours off the screen. It’s soundtracked by a passionately seductive score by Franx Waxman. As we watch these two fall into each other’s arms, the film tricks us (and, I think, itself) into thinking these two lovers deserve to be together. And, by extension, everyone would be much better off if Shelley Winter’s gratingly needy Alice, who can’t hold a candle to Elizabeth Taylor’s grace, charm and beauty, just disappeared. Before we realise it, we and the film are silently rooting for a man with fatal plans to rid himself of this encumbrance.

What’s striking reading about A Place in the Sun is that Clift felt Eastman, far from a sympathetic romantic, was an ambitious social-climber (much like his role in The Heiress) too feckless, weak and cowardly to face up to his responsibilities. Clift’s performance captures this perfectly: at the height of his method-acting loyalty, Clift is sweaty, shifty and increasingly guilt-ridden with Alice, awkwardly mumbling platitudes rather than talking (or taking) action. It’s actually a superb performance of people-pleasing weakness from Clift. Eastman always says what those around him want to hear, whether it overlaps with what he believes or not. He can say sweet nothings to Alice and romantic longings to Angela. This is a great performance of an actor being, in many ways, more clear-eyed than the film about what the story is really about: a man who decides the best way to deal with the inconvenience of a pregnant girlfriend is to drown her.

What Clift didn’t anticipate is how much the power of photography and editing (not to mention the radiance of his and Taylor’s handsomeness) would mean many viewers would end up rooting for the selfish romantic dreams of this weak-willed heel. Steven’s film turns the Clift-Taylor romance into a golden-age Hollywood dream. Taylor, at her most radiant, makes Angela possibly the nicest, kindest, most egalitarian rich girl you can imagine. Their undeniable click is there from their first real encounter (Angela watching George absent-mindedly sink a cool trick shot at an abandoned pool table – how many takes did that take?). The sequences of these two together play out like a classic idyll, from slow-dancing at glamourous parties to lakeside smooching. Everything about what we are seeing is programming us to root for them – and I’m not sure Stevens realises the implications.

If we are being encouraged to relate to Clift and Taylor, everything in Shelley Winter’s Alice is designed to make us see her not want to be her. Winters lobbied for the part, desperate for a role to take her away from shallow romantic parts – ironically her success pigeon-holed her to dowdy, needy second-choice women, deluded wives and desperate spinsters. But she’s superb here, making Alice just engaging enough for us to imagine George would take a break from his self-improvement books, but also so fragile and needy we can believe she’d become both increasingly desperate and annoying. Angela, dancing radiantly at parties, is who we want to be: Alice, sitting up late in her cramped flat with a try-hard birthday dinner and carefully chosen gift waiting for the arrival of an indifferent George, is who we fear we are. If movies are an escape, we don’t choose her.

Steven’s film makes Alice’s pregnancy more and more a trap. (The film carefully skirts the much discussed but never named abortion option). When on the phone together, the camera tracks slowly into George as he huddles against a wall mumbling, the film’s world shrinking with his. In one of the film’s many beautifully chosen Murnau-inspired super-impositions, Alice appears like a ghost over George and Angela at the river. Alice’s increasingly fractious demands that George do his duty and marry her, with increasingly wild threats of social disgrace interspersed with her grating, desperate neediness makes us cringe with him. Possibly because we worry we’d be like her.

A Place in the Sun makes us root for a man plotting murder and guilty, at the very least, of manslaughter. That could make it the most subversive romance of all time – if it wasn’t for the fact that, even in the end, George is presented as the real victim. Even a priest gives him only a few words of criticism, while George is not even punished by losing the love of the faithful and trusting Angela. Even if George didn’t push Alice in, he also didn’t lift a finger to save her life. In the trial, Raymond Burr’s showboating DA helps us pity George as he presents a version of that fateful boat trip that we know isn’t true but is only a few degrees more horrible than what George actually did. Even his guards feel sorry for him, and Steven’s clunkily intercuts between George’s dutifully honest working-class family and the wealth of his rich uncle’s circuit to hammer home the tragedy.

Did Stevens realise all of this as he made the film? I’d argue possible not: that he was as much sucked into the romance as the viewing audience. But some American movies embrace optimism – and an American tragedy in that world is lovers kept apart. A British tragedy is an ambitious man destroying himself and others. There is a smarter, more ruthless film to be made from the material of A Place in the Sun. One where Clift’s George is a truly heartless go-getter and both Alice and Angela are different types of victim. And that would be American to: it would be one which consciously shows us how our longing for fairy tales and the American Dream can lead to perverse, outrageous outcomes. That film would be a masterpiece, rather than the unsettling work A Place in the Sun actually is.