A star-turn and some good songs can’t quite make a shallow, over-long musical really work

Director: Morton DaCosta

Cast: Robert Preston (Harold Hill), Shirley Jones (Marian Paroo), Buddy Hackett (Marcellus Washburn), Hermione Gingold (Eulalie Mackechnie Shinn), Paul Ford (Mayor George Shinn), Pert Kelton (Mrs Paroo), The Buffalo Bills (The School Board), Timmy Everett (Tommy Djilas), Susan Luckey (Zaneeta Shinn), Ron Howard (Winthorp Paroo)

The Music Man is an ever-popular Broadway smash, the sort of charming, light, fun-filled musical with some good songs that makes it undemanding fun. It doesn’t, honestly, gain anything on screen – in fact, if anything, it’s fundamental lightness and lack of emotional or thematic substance gets rather exposed. The movie version may be ridiculously over-extended and frequently feel more like a slightly up-market filming of the Broadway production, but it’s still got some fine songs the best of them delivered with absolute aplomb by Robert Preston, masterfully recreating the Broadway role he had played nearly a thousand times already.

Preston plays Henry Hill, who arrives in the town of River City in Iowa in 1912 determined to sell instruments and uniforms to form a children’s band. Or at least that’s what he says he’s here to do: he’s actually a con man, whose plan is to sell the concept to the town, get them to invest, pass himself off as a music professor and then skip town with their money. Inciting a moral panic over a new Pool club opening in the town corrupting the kids (it will be ragtime next!), he wins them over. But it’s not all easy-sailing: librarian Marian Paroo (Shirley Jones) suspects Hill is not who he says he is. To try and protect his scheme, Hill aims to seduce her. But will this relationship actually help him find a conscience?

It’s a feel-good Hollywood musical so… I’ll leave you to guess. The Music Man is an odd musical. In many ways, you can see it as a slice of nostalgia, with its gentle 1910s setting and portrait of small-town America as a gentle, easy-going place where everybody knows everybody else, nobody locks their doors and the most dangerous thing is a pool table. But, at the same time, The Music Man frequently portrays its townspeople as staggeringly gullible (no one doubts Hill’s ‘imagination’ method of learning – don’t practice, just imagine you can play an instrument and you can!) and very hostile to outsiders (Hill receives the coldest, most suspicious of welcomes when he first gets off the train, even before he has announced any plan). Then, when he is exposed, their plan to tar-and-feather him sounds dangerously close to a lynching.

Put frankly, I have no idea what The Music Man is trying to say about small-town life or really anything else, seeming to want to have its cake and eat it by making the townspeople both a joke and an idealist past we can aspire to. Each of the characters is, in any case, a reassuring cliché. From Shirley Jones’ librarian (a mousy, but independently-minded intellectual who has never been kissed) to her mother (a blowsy, loud-mouthed Irish-woman who just wants a good man for her daughter), to the Mayor (a puffed-up, self-important idiot) and his wife (an attention-seeking moralist grande dame) to its sweetly love-struck teens, every character more or less feels like a stock figure carefully placed for comic or emotional impact.

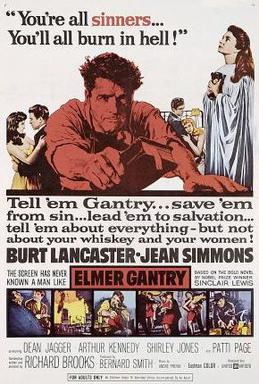

It also rather fudges the semi-redemption arc it feels like its aiming for with Hill. He brings back memories of Elmer Gantry (the presence of Shirley Jones – here cast to type as the sweet, virginial mark rather than an infuriated floozy – also helps with this), and you can see a certain similarity between that shameless opportunist and this egotistical showman determined to make an immoral buck. The Music Man, I think, wants to show Hill’s conscious growing as he gets closer to the townspeople: it’s slightly under-mined by the fact it continually plays the townspeople as jokes and Hill’s character has no real depth (he remains, more or less throughout, a friendly, amoral opportunist).

As such, it needs a surprisingly sudden pivot to give some genuineness to Hill (a few minutes before changing his mind, he’s literally joking about not leaving town until he’s earned the fruits of his seduction campaign by bedding Marian). The fact that this even vaguely works is largely due to Preston. In fact, almost anything that works is due to Preston. He had a Broadway triumph with the role, and Da Costa (director of the stage production) and writer Meredith Wilson insisted he got the role over preferred choices Bing Crosby, James Cagney and (most inexplicably) Cary Grant. And it’s great they did, because Preston is triumphant: magnetic, charismatic, funny and delivering the film’s best numbers with an energetic, sublime aplomb. His comic timing is perfect and he successfully makes a persistently lying, opportunistic shit immensely likeable.

He also nails the best songs. The Music Man may be slightly fudged in its themes and its exploration of its central character, but it does have some very striking, catchy musical numbers. ‘Ya Got Trouble’ (essentially an energetically sung, word-heavy, fast-paced monologue) is funny and brilliantly performed by Preston. Similarly, ‘Seventy-Six Trombones’ is a show-stopper from Preston and he brings real lyrical charm to ‘Gary, Indiana’. There are further fine numbers, from the inventive ‘Rock Island’ that opens the film (sung in imitation of a steam train) and ‘Shipoopi’ a high-kicking dance number.

This is all filmed with a decent competence but very little flair. Da Costa essentially re-creates his stage production with very little of the sort of dynamism and flair someone like Stanley Donen had. Da Costa also doesn’t accelerate the pace – the light plot stretches over a very long, two and a half hours (almost nothing really happens in the middle hour). Remove Preston from it and I’m not sure there would be enough there to hold anyone’s interest. In fact, with its shallow plot, lifting and shifting of an existing musical to a (more expensive) real location with no re-thinking of the material for a different medium and its over extended, epic run-time, you can sort of see in it the DNA that would go on to become some of the mega-flop musicals that would weigh down the studios in a few years. The Music Man was a smash hit (probably because when it works, it is fun) but many of those that followed would not be.

And, as a side note, I was stunned to find out, that this beat West Side Story to the Tony Award for Best Musical.