Eggers’ wonderfully atmospheric remake is creepy, haunting and quite extraordinary

Director: Robert Eggers

Cast: Bill Skarsgård (Count Orlock), Lily-Rose Depp (Ellen Hutter), Nicholas Hoult (Thomas Hutter), Aaron Taylor-Johnson (Friedrich Harding), Willem Dafoe (Professor Albin Eberhart von Franz), Emma Corrin (Anna Harding), Ralph Ineson (Dr Wilhelm Sievers), Simon McBurney (Herr Knock)

Robert Eggers dreamed so long of his own version of FW Murnau’s seminal vampire film (and Bram Stoker copyright infringement) Nosferatu, it was originally announced as his second film. We had to wait a bit longer, but it was well worth it. Eggers’ experience helped him create a film infinitely richer than I suspect he would have made ten years earlier. Nosferatu is an astonishing, darkly gothic, richly rewarding film, glorious to look at and a fiercely sharp exploration of the subtexts of both sources. It can never match the original’s seminal impact, but celebrates and elaborates it.

The story hasn’t changed dramatically from the one Murnau ripped off from Stoker. In Wisborg, junior solicitor Thomas Hutter (Nicholas Hoult) leaves his beloved wife Ellen (Lily-Rose Depp) for Transylvania and a lucrative land deal with the mysterious Orlock (Bill Skarsgård) that could lead to a comfortable life for him and his new wife. Unfortunately, there are three things he doesn’t know: firstly, the Orlock is a ravenously cruel vampire, with extraordinary supernatural powers; second his employer Knock (Simon McBurney) is an occultist worshiper of Orlock; thirdly, Orlock has used his mental powers for years to terrorise and groom Ellen from afar and Hutter’s presence is the final step in his scheme to control her. It won’t be long until a deadly curse plagues Wisborg.

Egger’s dark (but extremely beautiful) gothic film drips with atmosphere, gloomy shadows rolling over its elaborate sets, the drained out night-time shots reminiscent of the tinted black-and-white beauty of the original. The entire film is soaked in love for silent-era horror, with homages to Murnau, Dreyer, Sjöström and so many others I couldn’t begin to spot them all – though I loved Orlock’s gigantic shadowy hand creeping Murnau’s Faustus-like over Wisborg. The film drowns in folk horror, from its snow-capped Transylvanian countryside dripping in unspeakable hidden evils to the unreadable motives of a mysterious Transylvanian village.

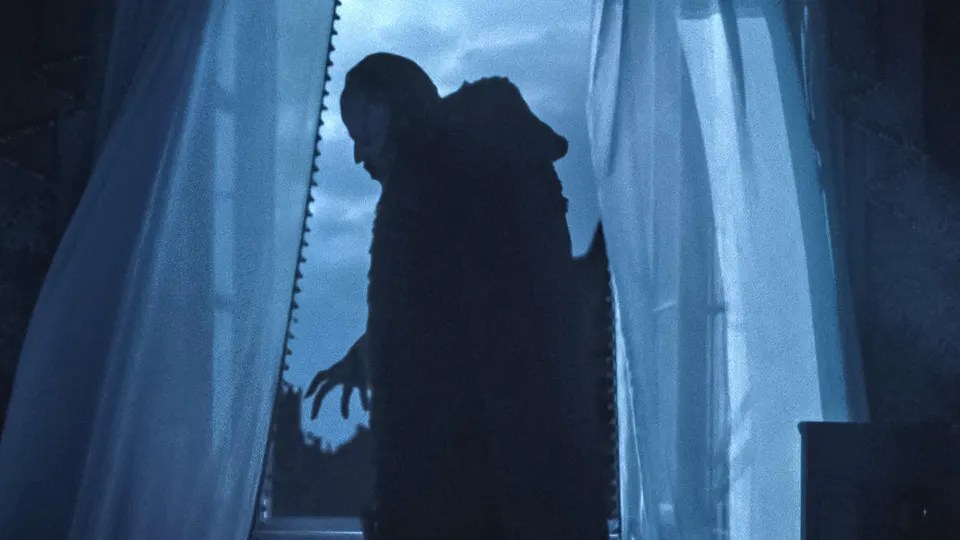

At its heart is an exploration of the sexual undertones of the vampire legend. Orlock’s assaults leave his victims are overwhelmingly sexual, with Orlock’s body thrusting forward while he drains the blood of his groaning victims. That’s not to mention Orlock’s revolting sexual manipulation of Ellen. Nosferatu leans heavily into Stoker’s dark sexual awakening subtext. Orlock’s psychological manipulation has left Ellen traumatised, torn between dark sexual desires and romance with Hutter. Nosferatu opens with a dark (dream?) sequence, as Ellen rises with sensual sighs from sleep, drawn towards Orlock’s seductive shadow in sheet curtains, before joining him outside for something that looks an awful lot like sex before Eggers cuts with a jump scare shot, our first glimpse of Orlock.

This is an Orlock radically different from Max Schreck’s original. While he shares his long nails and angular posture, here he is no-more-or-less than a decayed, rotting corpse. His body is covered in sores of decayed skin, with everything (including his penis) halfway to the compost heap, his bony legs and hips positively skeletal. There are homages to his Vlad the Impaler roots, from his fur-lined uniform coat (that like the rest of him has seen better days) to his surprisingly well-groomed moustache. But there isn’t a trace of the handsomeness of so many Draculas – this Orlock is possibly even more repulsive to look at than the rat-faced monstrosity of the original.

Skarsgård’s make Orlock a truly ruthless figure, delighting in his natural cruelty. With Hutter his looming, shadowy menace offers not a jot of home comforts, working to terrify a man who he sees as a perverse romantic rival. (His hallucinatory blood-sucking assault on Hutter is filmed in a manner reminiscent of rape). Throughout, he treats almost everyone he encounters with contempt and lofty disgust and takes a sadistic delight in torturing Ellen’s friend Emma Harding’s family, culminating in a truly shocking scene of grizzly horror. While the original Orlock was almost feral, like his rats, this one is a monstrous decayed sorcerer with a never-ending hunger and sadistic desire to play with his food.

He also has something the original never had: a voice. Skarsgård spent weeks in training to develop this (digitally unaltered) vocal range, a rolling bass-rumble which wraps itself around a raft of Dacian dialogue. Eggers’ gives him immense supernatural skills, in a film dripping with occult magic. Simon McBurney’s Knock (a remarkable performance) is a lunatic drowning in it: covered with dark markings, biting the heads of pigeons and communicating with Orlock by sitting naked in a Pentecostal star. His brain has been flushed out by Orlock’s mental power (who treats him like dirt) and the vampire’s hypnotic voice overwhelms the senses: just a few sentences drains Hutter of willpower (Nicholas Hoult’s fear is so palpable here you could almost touch it). Orlock’s malign influence can twist people or make them suddenly ‘wake’ with no idea of where they’ve been.

The power of his influence twists and distorts emotionally and physically. Lily-Rose Depp captures all this in a remarkable physical and vocal performance, as Ellen falls victim to Orlock’s mental manipulations. Depp throws herself into the most violent fits since Linda Blair: her body spasming, her voice distorted into an Orlock-mirroring gurgle, her eyes rolling back, her inhibitions falling away and blood weeping from deeply disgusting places, especially her eyes. Depp’s performance is extraordinarily committed, her fear and self-disgust at her manipulated sexuality (eekily from childhood) by the Count as tender as he hatred of him is sharp and all-consuming.

It’s never clear how far the vampire wants to screw Ellen, and how far he wants to consume her (Eggers even suggests, towards the end, that Orlock may even welcome his own destruction – perhaps the rapacious hunger is too much?). What is different from the original is Orlock and the plague he brings with him are different. While the original was a destructive force of dark nature, this Orlock is focused exclusively on punishing Ellen, with a literal plague striking down Wisborg.

In the face of this beast, the powers of science and reason are powerless (as Aaron Taylor-Johnson’s delicately performed Harding discovers, refusing to believe until its far too late). Like Murnau’s original, the powers of science and reason (such a key weapon against the vampire in Stoker) are useless. Even rationalist Dr Sievers (a fine performance by Ralph Ineson, channeling Peter Cushing and Michael Hordern) – a man so calm even the insanity of Knock can’t flap him – chucks in the towel and calls in Willem Dafoe’s barnstorming Professor von Franz (here considerably more effective than his counterpart), a scientist turned alchemist with deep occult knowledge.

But it can’t change the fact this is not a war between two sides, but a deeply personal struggle between Orlock and Ellen, with Hutter torn between them. Eggers’ focus on this personal story at the heart of a dark twisted legend adds a genuine freshness – and makes a superb counter-balance to the lashings of gothic horror the film soaks in. It makes for a superb remake that contrasts and comments on the original while telling its own story of dark, corrupted manipulation. Eggers’ direction is faultless in its atmospheric unease and there are superb performances from Skarsgård, Depp, Hoult and the rest. It’s a powerful work, overflowing with silent horror atmosphere while also feeling very modern that has the potential to haunt our nightmares as much as the original.