Tension and anxiety overwhelm a dark caper film that’s easier to respect than enjoy

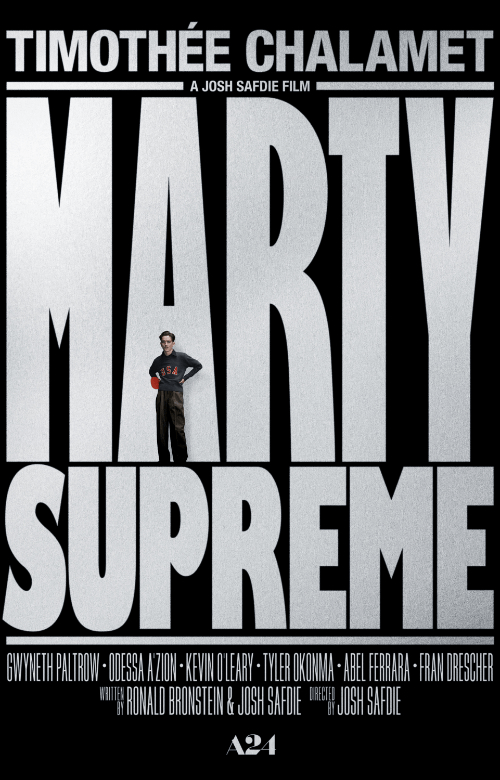

Director: Josh Safdie

Cast: Timothée Chalamet (Marty Mauser), Gwyneth Paltrow (Kay Stone), Odessa A’zion (Rachel Mizler), Kevin O’Leary (Milton Rockwell), Tyler Okonma (Wally), Abel Ferrara (Ezra Mishkin), Fran Drescher (Rebecca Mauser), Luke Manley (Dion Galanis), John Catsimatidis (Christopher Galanis), Géza Röhrig (Bela Kletzki)

It’s 1952 and Marty Mauser (Timothée Chalamet) is in the gutter aiming for the stars. A prodigiously talented table tennis player, he’s convinced it’s his destiny to become the world champion and face of the sport. To achieve this, he’ll go to any lengths lying, cheating and stealing. Marty relies on his relentless charisma to rope people in to support his increasingly risky scams and ploys. Among these are Rachel (Odessa A’zion), the married childhood friend he has got pregnant and Kay Stone (Gwyneth Paltrow) a retired Hollywood star, married to ruthless billionaire Milton Rockwell (Kevin O’Leary).

Marty Supreme initially feels like it’s going to be a plucky underdog sports movie, with triumph due to defeat over adversity. What it actually turns out to be is something far closer to Safdie’s Uncut Gems, an immersive, sometimes hard to watch study in a man almost unaware of how frantically (and self-destructively) he is trying to keep lots of balls in the air. The bulk of the film focuses on Marty going to increasingly desperate lengths to secure the funding to get to the Tokyo World Championships. This picaresque journey sails into a swamp of stress and tension, involving gangsters with missing dogs, gun-toting New Jersey rednecks, sporting jocks furious at being hustled at table tennis, corrupt policemen in Central Park and constant parade of dangers, humiliations and threats with the odd spark of jet-black humour.

This is shot with a close-focused, shaky-cam series of close-ups, jerkily edited that practically spreads the stress of the on-screen desperation and disguised fear to the audience. The dialogue is frequently a parade of shouting, as the furiously deceived or exploited scream in between the never-ending stream of bare-faced, confidently delivered lies from Marty. And at its heart is charismatic dreamer Marty, who believes rules don’t apply to him and whose chaotic impulse control constantly pushes things further than can safely go, leading to him constantly seizing failure from success. Go into this expecting a lot of fun and laughs and you are probably in for a disappointment: go on expecting to be put through the wringer, and you will be better prepared!

Marty is a not a million miles from a Trump or Boris: a man of charisma and persuasion able to influence people to things, despite his shameless track record of instinctive lies and selfishness. Chalamet gives an extraordinary, screen-burningly vivid performance creating a man of total and complete certainty that he has a special destiny and therefore the normal rules of life do not apply to him, making him completely comfortable with routinely using and then abandoning the people around him. The fact he does this but still makes it constantly understandable why so many people keep coming back to Marty (despite being constantly stung) is a tribute to his soulfulness.

Beyond his in-the-moment confidence, Marty is a desperate, almost-principle-free force-of-nature, constantly re-spinning himself and his actions to new circumstances or audiences. Outrages become triumphs, lovers become sisters, compromises become commitments… Nothing is as it seems. His ego is also stunning: he demands tournament organisers put him up in the Ritz (where he eventually abuses the free bar), seduces Paltrow’s movie star largely it seems out of wanting to be seen as an equal and throws a colossal temper tantrum when outmatched at a tournament.

He’s constantly reinventing himself. Ideas he rejects as ridiculous or humiliating – a tour as half-time entertainment for the Harlem GlobeTrotters or an exhibition match with his Japanese rival – are later repackaged by him as his own flashes of inspiration when he eventually decides to do them. He genuinely can’t understand why others don’t see his greatness, or why the table tennis authorities can’t see his grandstanding and temper on court might be the best thing to grow the sport in the American market.

Marty believes he has all the tools for success, but his vaulting ambition and relentless energy is constantly undermined by his recklessness and tendency to act and, most especially, speak before he thinks constantly blows him up. He frequently turns on would-be supporters and friends with spontaneous abuse or smart-arse comments. He isn’t cruel (he says “I love you” persistently after various rude comments), but the damage is done. Over the course of film he’ll make a shockingly off-colour Holocaust joke (even he clocks the reaction, nervously saying it’s okay he’s Jewish), mocks Rockwell’s loss of his son fighting the same Japanese he’s now doing business with and bluntly tells Rachel she can’t understand him because she is not special (like he is).

Marty is, however, a phenomenally gifted table tennis player. Marty Supreme’s shooting of the sport is electrically fast (Chalamet trained for months to master the fast-pace, wildly aggressive style Marty plays with) and its staging of the matches is a surprisingly relaxing and entertaining. Especially when compared to the nerve-shredding anxiety-inducing terror of Marty’s less than successful hustling and scam career. Chalamet’s injects subtle panic and desperation under his relentless confidence.

Confidence is secretly what is lacking from retired Hollywood star Kay Stone, played with a wearily amused energy by Gwyneth Paltrow, both flattered and intrigued by the much younger Marty’s interest (you can see In Paltrow’s face the enjoyment behind her surface exasperation), This helps spark a desire to kickstart her career with a Broadway play – an awful looking Tennesse Wiliams pastiche, co-starring a self-important Brando-style method actor she despises (and Marty humiliates, to her delight). Her desire to be loved again is clear. There is a lovely shot where an entrance applause sees her turn away from the audience and her face to break into a radiant grin. It’s the same buzz of feeling desired and loved that keeps her connected to the disastrous Marty.

It’s also an escape from a life comes under the domineering control of her husband, pen-magnate Milton Rockwell (a reptilian and superbly vile Kevin O’Leary). Rockwell’s selfishness and manipulation of people is far more ruthless than Marty’s naïve, childish self-focus. It’s one of a host of great supporting turns. Odessa A’zion gives Rachel a scammers natural instinct (pregnancy and all) under her genuine devotion to Marty. A’zion is terrific, genuinely confused about her own feelings for Marty, anxious but determined and as prone to self-destructive gambits as he is. Tyler Okonma is similarly excellent as his best friend constantly dragged into Marty’s dangerous, half-baked crazy schemes at high risk to himself.

Marty Supreme throws all this towards with a relentless cavalcade of energy which is often easier to respect than to really enjoy. It’s such an anxiety inducing film, both in its plot and the shooting style, that it can leave you feeling genuinely uncomfortable in your chair. Does it offer any hope for Marty? It’s ending can suggest a level of personal growth: but seeing as we have witnessed throughout the film flashes of instinctive decency from Marty that have been cast aside for his own ambitions, I wouldn’t be confident. But that discomfort is probably right for a film that’s almost trying to make you feel sweaty and uncomfortable in your chair.