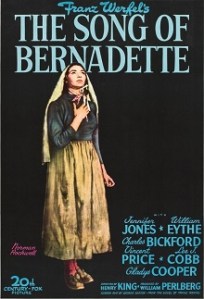

Well-meaning if slightly dry hagiography that struggles to turn history into drama

Director: Henry King

Cast: Alexander Knox (Woodrow Wilson), Charles Coburn (Professor Henry Holmes), Geraldine Fitzgerald (Edith Wilson), Thomas Mitchell (Joseph Tumulty), Ruth Nelson (Ellen Wilson), Cedric Hardwicke (Senator Henry Cabot Lodge), Vincent Price (William G McAdoo), William Eythe (George Felton), Mary Anderson (Eleanor Wilson), Ruth Ford (Margaret Wilson), Sidney Blackmer (Josephus Daniels), Madeline Forbes (Jessie Wilson), Katherine Locke (Helen Bones)

Darryl F Zanuck had a passion project: a biopic of the 28th President Woodrow Wilson. It would be both a tribute to a man, he felt, was overlooked and also a homage to current President Roosevelt – and a warning for the future. Like FDR, Wilson had introduced a raft of reforms and led the country in wars – and Zanuck was worried America would fudge the peace, just as Wilson had failed to get the Senate to endorse the League of Nations, leaving it a toothless lion.

Zanuck’s no-expense spared approach gives us a laudatory biopic that lavishes Wilson in euphoric praise, smooths off all his edges and presents him as a visionary and a near-flawless leader. The money was thrown into building elaborate sets and costumes – vast swathes of the White House and the Palace of Versailles were re-built on the sound stages of 20th Century Fox – and the script repackaged a series of major events interspersed with Wilsonian speeches. It was launched to a fanfare, was nominated (largely due to Zanuck’s influence) for ten Oscars (winning five) and was a box-office failure.

But is it a good movie? In truth, not quite. Despite the lavish production values, this is a dry, unimaginative and stately progression through its subject’s life. Henry King marshals events with the professionalism of an accomplished journeyman, but little inspiration. There is nothing striking, original or brave in a single minute of Wilson, but everything is perfectly framed and (considering its immense length) well-paced. King uses a series of low-angle shots to hammer home the magnificent detail of the sets and Alfred Newman’s score remixes a series of patriotic scores and heavenly-sounding choirs to build the impression of Wilson as secular saint.

But Wilson remains a largely undramatic movie, with an (Oscar-winning) script by Lamar Trotti that fails to inject drama or skilfully convey information. The warning signs are there in the film’s opening, with a group of New Jersey Democrats arrive to recruit Princeton head Wilson to run for Governor and clumsily give each other a potted precis of his CV and academic achievements while they wait for him to join them. Dialogue frequently info dumps historical research in our ears. Newspapers bluntly tell us in crude headlines what’s happening. Poor Thomas Mitchell’s entire role seems to be made up of running into rooms clutching telegrams announcing major events.

In amongst all this research though, we get very little idea of what Wilson actually stood for. There is virtually no time spent on his Governorship of New Jersey, other than a two-scene disagreement with the Democratic bosses whose power he breaks. On becoming President, his major legislative reforms are covered in a less-than-a-minute montage of signed bills. He consults his cabinet once or twice and, when war comes, walks a fine line between preserving American strength and not rushing into war. The final act of the film covers his failed battle for the League of Nations, the only policy the film invests any time into explaining.

For much of the rest of the time, this hagiography concerns itself with down-playing or skating over anything in Wilson that could be perceived as a flaw. Wilson here talks a good game of reform, equality and rights for all. In real life, he was a dyed-in-the-wool segregationist, sceptical about women’s suffrage as well as being an intellectually arrogant elitist who, later in his Presidency, began to see himself as a sort of vessel for God’s policies. While he was undoubtedly a highly effective moderniser and legislator, none of his faults make it to the screen.

Other areas are also carefully removed. Wilson was often accused of being heavily under the influence of advisors like “Colonel” House – House gets a one-scene cameo here. He ran for re-election in 1916 promising to keep America out of the war – this unfortunate broken promise is repackaged as Wilson sitting in the White House deeply regretting the campaign the party is running for him but stating there’s nothing he can do about it. His controversial re-marriage in 1915 to the much-younger Edith Galt (only two years after his wife died) is excused by his wife informing his daughters on her death bed that Wilson must marry again as he needs a wife. Wilson’s incapacity after a stroke in 1920 is down-played, while Edith (who effectively took over running the country for her husband in a constitutional scandal that would never stand today) states “I never made a decision without your knowledge and consent” while sitting with a sturdy Wilson.

All of this is played out in parallel with making Wilson’s rivals in the Senate mustachio-stroking schemers. None more so than Henry Cabot Lodge (well played by Cedric Hardwicke) who begins a career of animosity against the President after being made to wait for a meeting at the White House. In real life, Wilson refused any compromise offered by Lodge to get the League approved by the Senate, but here Wilson is a noble crusader foiled by political pygmies.

Saying that, the film benefits hugely from a very strong performance from Alexander Knox as Wilson, who not only looks and sounds exactly like the President, but perfectly captures his mannerisms. It makes you regret though the film is so little interested in Wilson’s personality or in building any picture of the humanity behind this leader. The rest of the cast have little to do other than state historical facts or stand to listen to Knox masterfully delivering Wilsonian speeches.

Wilson has a historical interest for Presidential buffs and, while it downplays the negatives around Wilson, it makes a very effective case for the President as a visionary leader (he was undoubtedly right about the League of Nations – even if his stance here is restructured into an FDRish self-determination for all nations). But this is a dry, stately film that never manages to turn the march of time into the thrust of drama. The Oscar-winning sets and photography look impressive, but its simplistic and hagiographic presentation of events eventually shakes your interest.