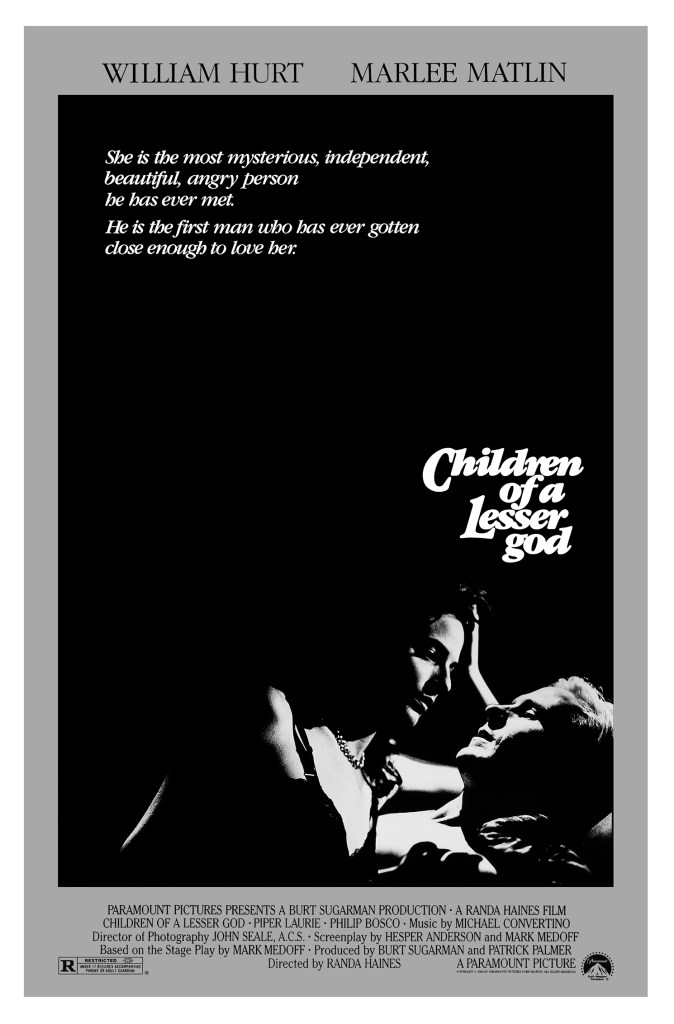

Clumsy Pygmalion drama that very uncomfortably mixes its messages during its obvious plot points

Director: Randa Haines

Cast: William Hurt (James Leeds), Marlee Matlin (Sarah Norman), Piper Laurie (Mrs. Norman), Philip Bosco (Dr Curtis Franklin), Allison Gompf (Lydia), Bob Hiltermann (Orin)

Adapted from a hit Broadway play, Children of a Lesser God (its title plucked from Tennyson’s The Passing of Arthur – though, like much of the film, I’ve no idea what point it’s trying to make) was hailed as a landmark in disability representation. Truthfully, it’s possibly slightly more retrograde than Johnny Belinda (made almost forty years earlier) and certainly not as good a film, its plodding plot and confused message not salvaged by two excellent performances.

James Leeds (William Hurt) is a charismatic teacher, newly arrived at a New England school for the deaf. His mission is to encourage the kids to speak, as he’s convinced they will struggle in the world on sign language alone. He becomes fascinated with the school’s janitor Sarah Norman (Marlee Matlin), a recent student, whipper-smart but defiantly silent, speaking only through fluent, witty sign language. Determined to teach her to speak and open-up a panorama of new opportunities for her, James and Sarah start a passionate relationship that increasingly flounders on the language barrier between them and Sarah’s own insecurities.

The positives first: both leads are excellent. Hurt is dynamic, engaging and charming – so much so it’s easy to overlook what a dick his character is (of which more later). Hurt accompanies all his dialogue with fluent sign language (no mean feat) and convinces utterly as the sort of maverick teacher who wins minds while carrying a prickly ego from uninterrupted success and validation. Opposite him, Matlin (still the youngest winner of the Best Actress Oscar) is electric: defiant, unaccommodating, sensual and damaged but able to burst into a radiant smile of confidence. Matlin makes her prickly but sensitive, defensive but determined and passion bursts out of her.

These two leads display obvious chemistry (although Matlin’s later recounting of Hurt’s serious domestic abuse during their relationship, barely denied by him, casts an uncomfortable shadow over the film). This lifts an otherwise straightforward film. It’s awash with expected plot points and beats from a meet-cute, to growing passion, falling outs and reconciliation. Aside from a few under-water shots (Sarah feeling completely comfortable under water, where her hearing is the same as everyone’s), it’s flatly filmed (it’s not a surprise Haines lost out a Best Director slot to David Lynch for Blue Velvet) and would not have looked out of place as a TV movie-of-the-week.

However, it’s main issues are the plays it makes for representation, while presenting deafness as an obstacle where the onus is on the deaf people themselves to fit in as much as possible. For a film about two people struggling to find a middle-ground between sound and silence, it never once dares us to experience the world as Sarah does. From its insistent score onwards, sound is an ever-present. None of Matlin’s dialogue is subtitled (she speaks aloud only once), with all of it translated by Hurt. For a film about finding common ground, its not interested in letting us experience even a taste of Sarah’s world.

Would it have killed them to have one scene where, perhaps, we walked around the school hearing what Sarah hears (nothing)? Or a scene where James and Sarah speak only through sign, with captioned translation? Instead, without really realising it, the film largely vindicates James’ position that not being able to speak is an abnormality Sarah is sticking to out of wilful, self-damaging stubbornness, rather than a choice she is entitled to make to engage with the world on her terms.

Unpack this stuff, and suddenly the whole film is a confusing mess of unclear positions and perspectives. James’ maverick teacher – in true Dead Poet’s style he wins the kids over by being unstuffy – is peddling a message that the deaf kids would be better off, if they became as much like him as possible. The film never once comments on James ignoring the one student in his class immune to his charm, essentially exiling him from his ‘in crowd’ during class. Is this great teaching? James has an unattractive messianic complex and a large part of his initial interest in Sarah is based on an arrogant belief that he can ‘save’ her from life as janitor, expecting her gratitude in return.

This Pygmalion like set-up quickly demonstrates it has way less insight about the self-occupied arrogance of its teacher than Shaw. It becomes clear to Sarah, that her successes (and the successes of James’ students, who under his tutelage perform a song-and-dance routine at parents day) are seen as his successes. When she wows James’ colleagues at a poker night with her wit and skill, they praise him (right in front of her), which he soaks up with a smug pleasure. The film never quite puts these dots together, or sees the irony in James’ bored disengagement with her deaf friends or his giving up on explaining Bach to her.

Worse than this, James ignores her early comment that she doesn’t want to be made to speak (she tells him that, as a teenager, she used sex to silence boys who pushed her to talk). Despite his vows, he increasingly, insistently demands she speaks, and fails to recognise when she resorts to using sex to try and shut him up. The film never pulls him up his selfishness and pushy imposing of his views, its sympathy for Sarah not changing its quiet view that her own problems are a major brick in the wall between them.

The film doesn’t really question James’ arrogance, because it can’t shake its habit of viewing her a problem to be solved. It effectively endorses James’ view that she should adjust and change as much as possible. Is it really wrong for Sarah to want to live on her own terms, not other people’s? To refuse to perform as James demands?

In fact, much as the film wants us to dislike Philip Bosco’s rules-bound obstructive headmaster, he makes two very valid points: one, it’s not for James to decide what’s best for Sarah and it’s not appropriate for James to fuck someone who is both a junior member of staff and (effectively) his student. Children of a Lesser God doesn’t even try to explore the moral complexities of any of this, instead settling for the idea that a disability can be overcome if someone works hard, overcomes their own issues and defers to an inspirational teacher. Combine that with its plodding, unoriginal story and you’ve got a film that hasn’t aged well.