|

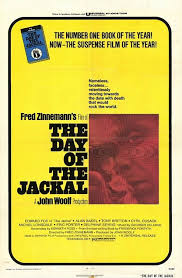

Paul Douglas and Richard Widmark race against time to prevent plague in Panic in the Streets |

Director: Elia Kazan

Cast: Richard Widmark (Lt Commander Clint Reed), Paul Douglas (Captain Tom Warren), Barbara Bel Geddes (Nancy Reed), Jack Palance (Blackie), Zero Mostel (Raymond Fitch), Alexis Minotis (John Mefaris), Dan Riss (Jeff), Guy Thonajan (Poldi), Tommy Cooke (Vince Poldi)

It feels like a very modern nightmare: a plague of catastrophic proportions breaking out in a major city and threatening to wipe out thousands of people. This feeling helps to make Panic in the Streets feel more like a film from today rather than the 1950s. The only thing missing is a terrorist angle – everything else could have been pulled from the nightmare fuel of our modern age.

In New Orleans, a murdered man is found near the docks. The emergency button is pressed when the coroner detects a deadly infection. Naval doctor (and emergency co-ordinator) Lt Commander Clint Reed (Richard Widmark) quickly takes command and determines that the victim carried pneumonic plague before being shot. Tracking down the men who killed him, and who may also be carrying the disease, becomes urgent, before the infection spreads. The authorities don’t want panic, so Reed and Captain Tom Warren (Paul Douglas) – initially of course reluctant partners – must work together to quietly track down the killers. The killers meanwhile, Blackie (Jack Palance) and his crew, continue regardless with their small-town crime empire building.

Panic in the Streets was one of the first films to shoot extensively on location – and it’s a brilliant choice, as Elia Kazan’s use of real life, grimy, New Orleans locations, from back streets to the docks, is pivotal for the sense of urgency and realism that runs through the entire film. Kazan’s camera work is brilliant throughout, and it adds a real gritty sense of danger to the entire film. It’s also brilliant that he selects possibly the least attractive parts of New Orleans for his locations – Blackie’s world of run-down buildings and dives just feels perfect for the film.

Kazan keeps the focus tight and avoids too many distractions from the film’s narrative – except maybe some tiresome insights into Reed’s slightly troubled domestic life (with Barbara Bel Geddes in a particularly thankless role as his wife, who alternates between supportive and the inevitable just wanting him at home more). Other than that, the film follows Reed’s search in forensic detail, from questioning suspects to working out the radius of possible infection. There is more tension here in a meeting with the city mayor to try and wrestle the authority Reed needs to carry out his job than in dozens of car chases.

The script is tightly written, and focused on plot over character, but still allows moments for character beats that good actors can seize upon. Widmark makes Reed a driven professional, who still has enough personal insight to register that his flaws include arrogance and impatience. In many ways an interesting piece of counter-casting, Widmark’s slightly menacing air is inverted really well as a doctor frustrated by the lack of understanding he encounters from those he is trying to save from a potentially deadly infection. He’s the perfect actor for a character who is a hard-bitten professional with a ruthless streak, and who’s a little hard to like.

He has a great foil in Paul Douglas as a professional, down-to-earth, but skilful and whip-smart police detective. One of the film’s pleasures is the bond that slowly grows between this odd couple – it’s not unexpected if you’ve ever seen a movie before, but it is very well done. The film, however, is almost stolen by Jack Palance as the villainous heavy, intent on empire building and oblivious to the fact that he is probably carrying a deadly plague that could wipe out half the population. Equally good is Zero Mostel as his weaselly, sweaty side-kick.

It’s odd watching it now that the authorities aren’t more terrified by the prospect of such a deadly infection – but that is a sign of how things have changed since the film was released. It’s sometimes a rather cold film, fascinated by slimmed down procedure – from the procedures of tracking people down, to the inoculations Reed administers right, left and centre to those who may be exposed. Despite this general mood, Kazan still gets the tone just right for the later shoot out that tops off the film.

Panic in the Streets does have a few too many slower moments. The scenes showing Reed’s home life are particularly drab – although we do get a marvellous scene with his wife where Reed acknowledges that his attitude to Captain Warren has been arrogant and condescending. The politics of lowlife New Orleans criminals are completely dependent on the charisma of the actors – remove Palance and Mostel’s performances and they would be exposed as dull and irrelevant. But the rest of the time, the film has a genuine feeling of grimy reality and keeps the pace up a treat. It’s a little B movie gem that feels ripe for discovery in our terror-obsessed modern world.