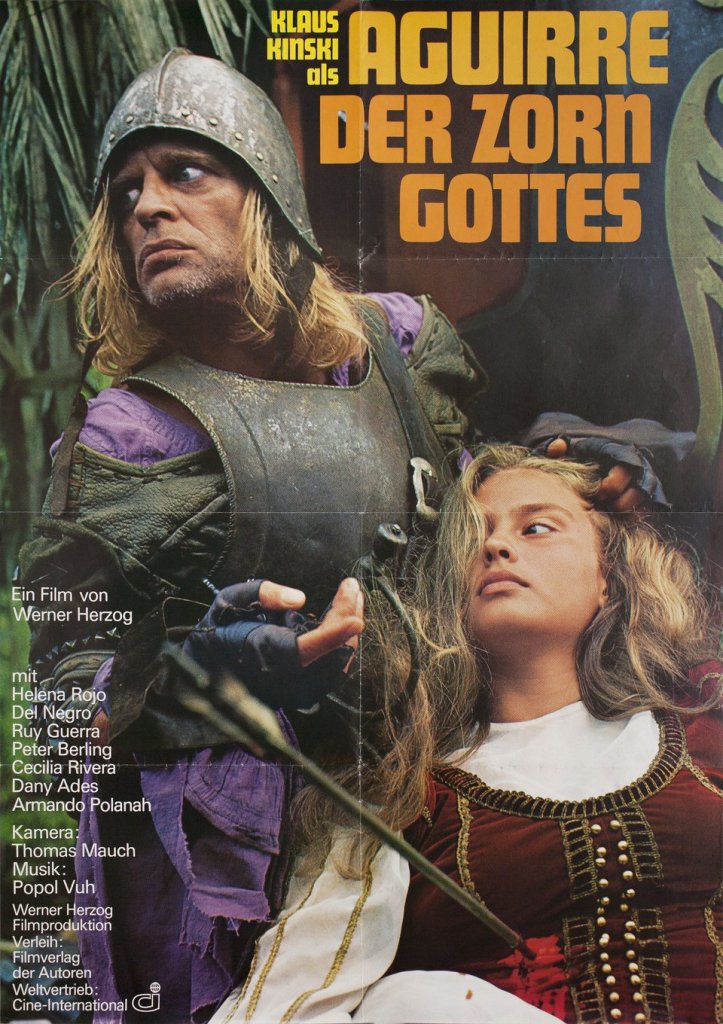

Herzog’s visionary epic remains one of the most impactful, haunting films in history

Director: Werner Herzog

Cast: Klaus Kinski (Don Lupe de Aguirre), Cecilia Rivera (Flores de Aguirre), Ruy Guerra (Don Pedro de Ursua), Helena Rojo (Inés de Atienza), Del Negro (Brother Gaspar de Carvajal), Peter Berling (Don Fernando de Guzman), Daniel Ades (Perucho), Armando Polanah (Armando), Edward Roland (Okello)

I first saw Aguirre, Wrath of God when I was young, a late night BBC2 showing. I’d never seen anything like it – and, to be honest, I’m not sure I have since. But then I am not sure anyone has. Aguirre was Herzog’s calling card and its haunting bizarreness, unsettling intensity and its mixture of extremity and simplicity is echoed in almost everything the eccentric German has made since. It seeps inside you and is almost impossible to forget, offering unparallelled oddness and lingering new nightmares every time.

It’s based on a heavily fictionalised piece of history, a rambling, possibly invented (and certainly over-elaborated) event: the mutiny of Don Lupe de Aguirre (Klaus Kinski) during the Conquistador campaign in the Amazonian remains of the Incan Empire. Pizarro has led an overburdened expedition into the depths of the rainforest searching for the untold (and fictional) riches of El Dorado. Don Pedro du Ursua (Ray Guerra) is sent with a party to explore down the river, with Aguirre as second-in-command. Further disaster occurs, as Aguirre launches a coup, installs puppet ‘emperor’ Don Guzman (Peter Berling), decides to seize El Dorado for himself and descends into a megalomaniacal madness, dreaming of building grandiose castles in the sky and toppling the Spanish monarchy.

Herzog filmed this fever dream of exhausted, starving and lost characters (and, indeed actors!) struggling to tell truth from mirage. The stunning visuals and locations are matched with the immediacy of water-splashed, mud-splatted lenses capturing the action. Aguirre is one of the most immersive films ever made, not least because as we watch cannons being dragged through rainforest, actors trudge down the side of mountains in the rain or cling to barely submerged rafts through rapids, we seem to sharing the experience of people doing all this for real.

Aguirre is book-ended by two of the most haunting shots in cinema history. Herzog’s opening flourish pans down the side of a mountain – one side of the shot showing the mountain, the other the mist – its disconcerting orientation (it’s easy to think you are seeing a birds-eye view, until you spot the actors climbing down the narrow path) made even more unsettling by the electronic mysticism of Popol Vuh’s music. This shot’s beauty and subtle terror is topped only by the final shots, of Aguirre prowling alone on a ruined raft surrounded by the dead and a ‘wilderness’ of monkeys (bringing to mind Shakespeare vision of a land not worth the cost in love). Between these bookends unfolds a film that will long live in the memory.

Aguirre is about obsession and madness but also failure. It’s so steeped in failure and hubris, it practically starts there. What else are we to think as we watch the conquistadors flog through the forest, dressed in hideously unsuitable clothes (armour for the men, dresses for the ladies), dragging cannons, relics and luckless horses behind chained Incan slaves? From the moment Pizarro calls a halt, it’s clear the search has failed. What the rest of the film demonstrates is how this failure only grows under the burden of relentless greed and vaulting ambition.

Greed powers everyone down this river: greed for the El Dorado’s gold and the power it might bring. It’s leads men to follow Aguirre’s mutiny and sustains them as their journey becomes ever more wild-eyed. No one is exempt: certainly not the Church, represented by hypocritical yes-man Brother Gaspar (Del Negro) who responds to mutiny by muttering that, regretfully, the Church must be ‘on the side of the strong’ – but doesn’t let that regret get in the way of serving as prosecutor, judge and jury in a kangaroo court for Don Ursua or happily stabbing to death an indigenous fisherman (who he gives the last rites) for blasphemy after the poor man confusedly drops a Bible on the floor.

But Aguirre’s hungers seems purely for power, with gold almost an after-thought. He’s far different from the mission’s newly elected ‘Emperor’, bloated glutton Guzman, who veers between stuffing his mouth with the limited rations or passing ludicrously high-handed regal pronouncements. Aguirre wants something more: complete and utter willpower over his surroundings. He doesn’t need to be commander for this: knowing he holds the power is enough, the ability to control life and death for his men.

Much of Aguirre’s magnetic, horrifying dread comes from the qualities in the man who plays him. Kinski’s performance is strikingly terrifying, his stiff-framed walk (based on Aguirre’s real-life limp) as judderingly disturbing as the retina-burning glare of his stare, the bubbles of incipient madness and the relentless determination to do anything (from blowing up a raft of his own men to beheading a potential mutineer) that will keep his will predominant. Aguirre’s perverse desire for control extends to an unhealthy interest in his daughter (something very unsettling today, with our knowledge of Kinski’s own appalling actions) and curls himself into the frame like a hungry tiger waiting to pounce, unleashing himself for demonic rants to cement his power and ambitious plans.

As with so many Herzog films, the longer the journey, the more fraught it becomes with perils, greed and madness. The film invites us to watch an expedition that started teetering on the edge of sanity, topple into violence, death and despair. Perhaps that’s why Ursua is spared, to join us in watching in stubborn, appalled silence the rafts drift aimlessly down river, men picked off one-by-one by unseen forces while their minds slowly fracture. Herzog uses the mute Ursua as a horrified surrogate for us, his blank incomprehension mirroring our shock at how far men can slump.

The worst elements of many of them emerge. The monk who preaches the word while complacently doing nothing and dreaming of a golden cross. Guzman’s obese Emperor, guzzling food while his desperate men starve. Aguirre’s psychopathic sidekick Perucho, who whistles casually when taking on Aguirre’s dirty work. Others collapse into shocked stupor: Aguirre’s daughter, who can’t seem to process what’s happening around her; Ursua’s lover Ines (Helena Rojo) whose hopes to reverse the mutiny tip into suicidal defiance and the stunned, tragic, imprisoned Incan prince re-named Raphael, forced to witness the self-destruction of men who looted his country and are never satisfied.

Aguirre’s Conrad-istic vision reeks of colonial criticism. As these arrogant ‘civilised’ men, charge downriver into madness and death, they remain convinced they can control the environment around them. The people of the Amazon to them are savages or slaves in waiting, any gold they find theirs by right. Aguirre himself is like some nightmare collection of every single rapacious European ruler who wanted to tear a chunk off a map and claim it as his own: even in failure and death, he still sees no reason to stop, only to press on, claiming more land, wealth and power. It’s this terrible truth that give Aguirre such continued power and relevance.

Herzog’s film builds beautifully to inevitable destruction, but it matters not a jot to Aguirre, content with his complete control over a raft of dead men. Herzog films it unfold in a haunting mixture of static shots, carefully framed compositions inspired by Spanish paintings (including a bizarrely formal coronation shot of Guzman), accompanied by a chilling silence or the unsettlingly eerie sounds of Vuh’s music or the pipes of an Incan bearer. Aguirre, perhaps more than any other film, exposes the horrific hubris of empire building, the pride and greed that lies behind it and the piles of unsettling bodies (guilty and innocent) left in its wake.

It’s a film that deserves to be famous for more than just the crazed stories of its making. The clashes between Kinski – an impossible, wicked, man but a celluloid-burning presence – and Herzog are legendary (it was the film where Herzog threatened to shoot the ferocious star and then himself if Kinski followed through on walking out mid-shoot). But just as stunning is the film’s haunting, lyrical mysticism and the fierceness of its savagery. It can have a vision of a ship in the heights of the trees and a head that finishes its countdown separated from its body. It can leave you so deeply unsettled, so hauntingly present that it will stick with you as it has stuck with me for over twenty years, giving new remarkable visions every time I re-watch it.