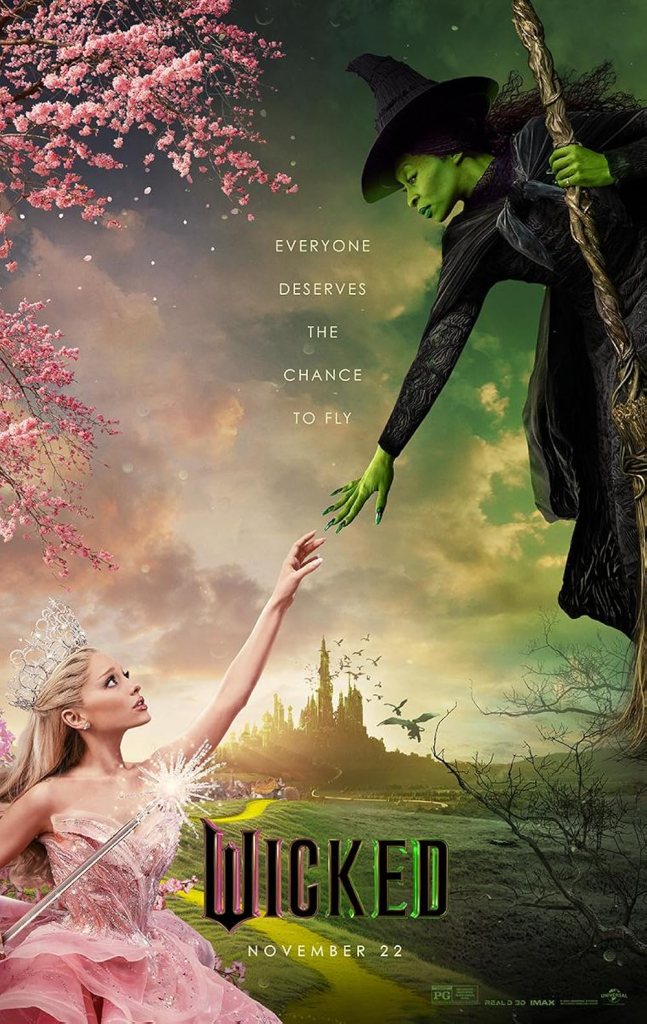

Hugely enjoyable and electrically filmed (sung and danced) adaptation of the classic stage musical

Director: John M. Chu

Cast: Cynthia Erivo (Elphaba Thropp), Ariana Grande (Galinda Upland), Jonathan Bailey (Fiyero Tigellar), Michelle Yeoh (Madame Morrible), Jeff Goldblum (Wizard of Oz), Ethan Slater (Boq Woodsman), Bowen Young (Pfannee), Marissa Bode (Nessarose Thropp), Peter Dinklage (Dr Dillamond), Bronwyn James (Shenshen), Andy Nyman (Governor Thropp)

I might be the only person who missed the phenomenon of Wicked, a smash-hit musical that filled in the back story of The Wizard of Oz. Set long before the arrival of Dorothy and her march down that yellow brick road, it covers the meeting and eventual friendship of Elphaba (Cynthia Erivo) future Wicked Witch of the West and Galinda (Ariana Grande) future Glinda the Good, at Shiz University (a sort of Ozian Hogwarts). Wicked is a grand, visual spectacular crammed with memorable tunes and show-stopping dance numbers and it’s bought to cinematic life in vibrant, dynamic and highly enjoyable style by John M. Chu.

At Shiz, Elphaba is snubbed by all and sundry who can’t see past her green skin. Despised by her father (Andy Nyman) – who we know isn’t her true father (I wonder who it could be?) – she’s lived a life of defensive self-sufficiency. Galinda, in contrast, is effortlessly popular and has never found herself in any situation where she can’t get what she wants. But Elphaba has something Galinda wants – a natural talent for magic that makes her the protégé of Madame Morrible (Michelle Yeoh) – and circumstances end up with the two of them sharing rooms. Surprisingly, a friendship forms when these two opposites find common ground. But will this be challenged when Elphaba is called to the Emerald City to meet with the Wonderful Wizard of Oz (Jeff Goldblum)?

Wicked Part One covers (in almost two and half hours!) only the first act of Wicked, meaning the film culminates with the musical’s most famous number ’Defying Gravity’. The producers proudly stated this was to not compromise on character development by rushing – the more cynical might say they were motivated by double-dipping into mountains of box-office moolah. Despite this, Wicked Part 1 (despite taking pretty much as long to cover Act 1 as it takes theatres to stage the entire musical) feels surprisingly well-paced and the film itself is so energetic, charming and fun you quickly forget the fundamental financial cynicism behind it.

Wicked is directed with real verve and energy by John M. Chu – it’s easily the most purely enjoyable Hollywood musical since West Side Story and one of the most entertaining Broadway adaptations of this century. Wicked is expertly shot and very well edited, its camerawork making the many dance sequences both high-tempo and also easy to follow (Wicked avoids many musicals’ high-cutting failures that make choreography almost impossible to see). And it looks fabulous, the design embracing the bold colours and steam-punk magic of Oz.

It also perfectly casts its two leads, both of whom are gifted performers bringing passion and commitment. Cynthia Erivo’s voice is spectacular, and she taps into Elphaba’s loneliness and pain under her defensive, defiant outer core. It’s a fabulously sad-eyed performance of weary pain and Erivo beautifully conveys Elphaba’s moral outrage at the lies that underpin Oz. Just as fantastic is Ariana Grande. Grande says she had dreamed about playing Galinda since she was a kid (yup, that’s how old this musical is) – and it shows. It’s an electric, hilarious performance that embraces Galinda’s studied sweet physicality, her little bobs and flicks and blithe unawareness of her aching privilege and self-entitlement, but what Grande does stunningly well is really make you like Galinda no matter how misguidedly self-centred she is.

And she really is. Part of Wicked’s appeal is mixing Oz with Mean Girls with more than a dash of racial prejudice. Elphaba is immediately snubbed because she literally doesn’t look right (anti-green prejudice is an unspoken constant) compared to Galinda’s pink-coated, blond-haired perfectness. Galinda is Shiz’s queen bee, followed everywhere by two sycophantic acolytes (delightfully slappable performances from Bowen Young and Bronwyn James) who cheer everything she does and push Galinda to maximise her subtle hazing of the green-skinned outsider. After all, they see popularity as a zero-sum game: the more Elphaba might have, the less there must be to go around for them.

It’s not really a surprise that Elphaba has had a tough time. Oz is dripping with prejudice, racist assumptions and strict hierarchies. From the film’s opening number – ‘No one mourns the wicked’, where Munchkins wildly celebrate Elphaba’s future death – we are left in little doubt there is a culture of blaming those who are different for misfortunes. This sits alongside a purge of unwanted citizens: namely talking animals. Goat professor Dr Dillamond (a lovely vocal performance from Peter Dinklage) is subtly belittled for his goat-accent then dragged in disgrace from the school. A new professor extols the virtues of keeping frightened animals in cages. The casting of Jeff Goldblum helps with creating this genial but cruel world, his improvisational mumbling suggesting a man of arrogant, sociopathic distance under initial aw-shucks charm.

These secrets will impact the friendship between our leads. The extended runtime means it already takes a very long time for the ice between them to thaw (and, for me, their ballroom reconciliation doesn’t land with the cathartic force it needed for the transition from hostility to friendship to completely work), but the exceptional chemistry between Erivo and Grande helps sell it. What Wicked does very well though is show the fault-lines in this relationship. Galinda’s answer to all Elphaba’s problems is for her to be more like her, while Elphaba has clearly never had a real friend in her life and wants one more than anything. There is true kindness and love between them, but Elphaba remains an outsider with cause to be angry against the system while Galinda is the ultimate insider for whom the system has always worked. Wicked Part 1 does a very good job of never letting these facts escape your notice, for all the charm of an unexpected friendship.

Wicked Part 1 though is also a monstrously entertaining film. The song and dance numbers are spectacular – the pin-point choreography of ‘What Is This Feeling’ is superb, while the power ballad intensity if ‘The Wizard and I’ is perfectly nailed by Erivo. Jonathan Bailey comes close to stealing the limelight with a show-stopping turn as the charming, likeable but slightly rogueish Fiyero, his ‘Dancing Through Life’ routine in particular being a stunning display of athletic dancing matched with perfect vocals. Every number is given its own carefully judged tone, with wonderfully complementary photography and editing, to create a film that leaves you eagerly wanting more.

I didn’t really know the musical coming into it, but after Jon M Chu’s excellent production, I’m excited to see what happens in Part (Act) 2.