Comic-drama about business collapse wants to The Social Network but lacks its deft touch and humanity

Director: Matt Johnson

Cast: Jay Baruchel (Mike Lazaridis), Glenn Howerton (Jim Balsillie), Matt Johnson (Doug Fregin), Rich Sommer (Paul Stannos), Michael Ironside (Charles Purdy), Martin Donovan (Rick Brock), Michelle Giroux (Dara Frankel), Saul Rubinek (John Woodman), Cary Elwes (Carl Yankowski)

“We’ll be the phone people had before they had an iPhone!” I’ve always found successful products that collapsed overnight fascinating. The Blackberry tapped into something people didn’t even realise they wanted: a phone that combines a computer and pager, a status symbol that told everyone you were a Master of the Universe. It was the product everyone wanted – until Steve Jobs announced the iPhone that did everything the Blackberry did better. It should be material for an entertaining film – but Blackberry isn’t quite it.

The film is set up as a classic Faust story. Our Faust is Mike Lazaridis (Jay Baruchel), co-founder and CEO of Research in Motion, a tiny Canadian business with an idea for lovingly crafted cellular devices. Our Mephistopheles is Jim Balsille (Glenn Howerton), an aggressive blowhard businessman who sees the potential – and knows he can sell it the way the timid Lazaridis never could. The angel on Faust’s shoulder is co-founder Doug Fregin (Matt Johnson), who worries the quality-and-fun parts of the business will be sacrificed. Nevertheless, Mephistopheles tempts Faust into partnership and they turn Blackberry into a huge business destined to all fall apart.

Blackberry desperately wants to be The Social Network. What it lacks is both that film’s wit and sense of humanity. It’s a film trying too hard all the time, always straining to be edgy. You can see it in its hand-held, deliberately soft-focus filming style, the camera constantly shifting in and out of blur. (Watching after a while I genuinely started to feel uncomfortable, with a wave of motion sickness nausea.) It goes at everything at one hundred miles an hour, but never manages to make its depiction of a company bought low by arrogance and unwillingness to adapt either funny or moving. It’s aiming to capture the chaos, but instead feels slightly like a student film.

It’s Faustian theme of selling out your principles for glory is just too familiar a story – and the dialogue isn’t funny enough to make the film move with the zingy outrageousness it’s aiming for. It also lacks momentum, the woozy hand-held camerawork actually slowing things down, a very shot lurches into focus. It’s a film crying out for speedy montage and jump-cuts to turn it into a sort of cinematic farce, as the business makes ever more sudden, chancy calls which switch at the mid-point from paying off to unravelling. Instead, it stumbles around like a drunken sailor.

At the centre, Jay Baruchel delivers the most complex work as the awkward and timid Lazaridis who slowly absorbs more and more smart business styling and ruthlessness over the film. But the film fumbles his corruption. His opening mantras – that “good enough is the enemy of humanity”, that Chinese mass production equals low quality because the workers aren’t paid enough to care about the product, that companies should focus on human needs – are all-too obviously dominos set up to get knocked over as Lazaridis gets corrupted and cashes out his principles to turn out exactly the sort of bug-filled mass-produced crap he railed against at the start – but this makes the character himself feel more like a human domino himself rather than living, breathing person.

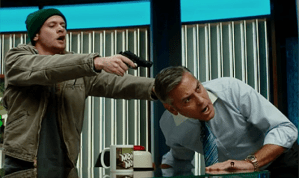

The other performances all verge on cartoonish. Glenn Howerton channels Gordon Gekko and The Thick of It’s Malcolm Tucker as abusive, sweary, would-be Master-of-the-Universe, only-interested-in-the-bottom-line Jim Balsille. Balsille will do everything Lazaridis won’t do: he’ll cut corners and browbeat his way into meetings. A smarter film would make clear Balsille is in many ways more effective than Lazaridis – that without him Research in Motion would have gone bust years ago. It could also have looked with more sympathy at a guy who so believed in his one shot at glory he re-mortgaged his house to pay for it. But the film leans into Howerton’s skill at explosive outburst and never really humanises him, constantly shoving him into the role of villain.

The film also fails with its more human element. Director Matt Johnnson plays Doug Fregin, Lazaridis’ best friend and business partner. Fregin is set-up as the angel in Lazaridis shoulder, the decent guy against selling out. But Johnson’s performance lacks charm or likeability. Fregin – like many of the other workers of the company – is a geek-bro, his veins pumping with fratboy passions, who thinks the best way to get people working is to throw a string of parties. He’s, in a way, as wrong as Balsille is on what makes long-term business success. Crucially as well, the friendship between him and Lazaridis never really rings true, not least because Fregin browbeats and bullies the timid Lazaridis as much as Balsille does.

With no-one to really care for, the tragedy of this business never hits home. It does capture the sense of desperation as the once-mighty company collapses in the face of Apple – Lazaridis ramming his head into the sand and refusing to believe anyone would want a phone sans keyboard – but it fails to successfully illustrate why an innovator lost his ‘magic’ touch. The script fails to land much of its humour, and tiptoes around positioning Lazaridis as increasingly corrupted, even as starts hiring brash businessmen (epitomised by Michael Ironside’s sergeant-major fixer) to say the thing to his underlings that he’s too scared to. The financial shenanigans that land Blackberry in trouble with the SEC aren’t properly explained, and the actual reasons the iPhone finally put Blackberry in the dust bin of history are hand-waved away (“minutes… data… look just accept it ok”)

Blackberry would, in the end, have been better as an hour-long documentary, with dramatic reconstructions supported by informative talking heads. The film we have fails to deliver on a concept that bursts with comic and dramatic potential.