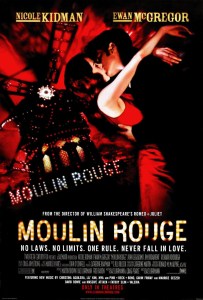

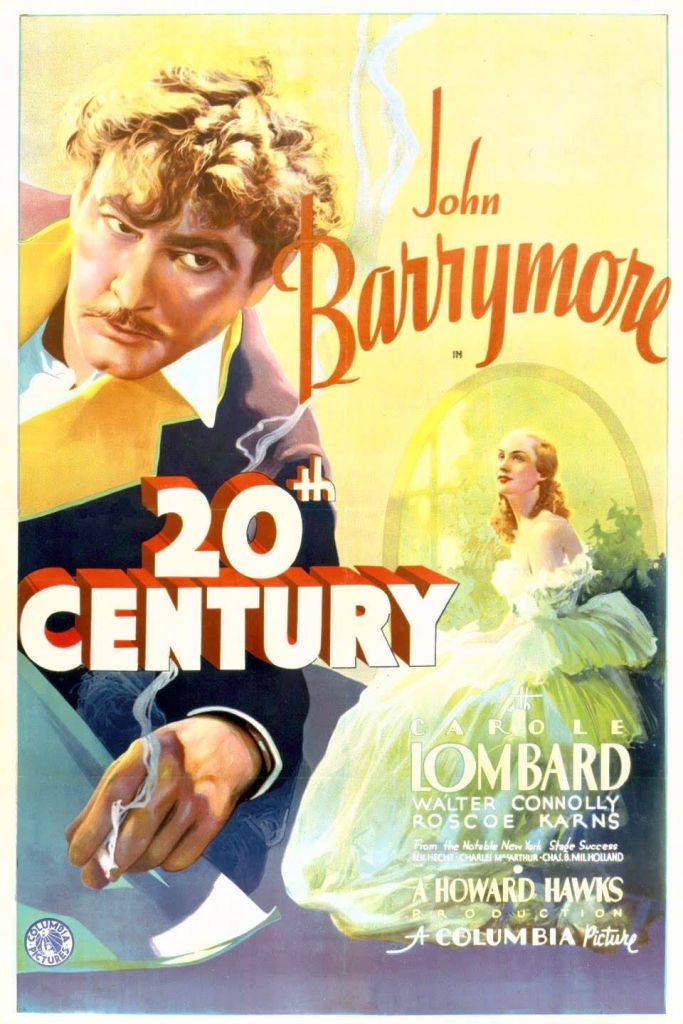

A producer and his muse bicker, feud and fall in love in the theatre in this funny proto-screwball

Director: Howard Hawks

Cast: John Barrymore (Oscar Jaffe), Carole Lombard (Lily Garland), Walter Connolly (Oliver Webb), Roscoe Karns (Owen O’Malley), Ralph Forbes (George Smith), Charles Lane (Max Jacobs), Etienne Girardot (Mathew J Clark), Dale Fuller (Sadie), Edgar Kennedy (Oscar McGonigle)

Oscar Jaffe (John Barrymore) is the biggest showman on Broadway. He can take the rawest stone and polish it into the brightest diamond. Lily Garland (Carole Lombard) is just such a stone, a lingerie model turned superstar of stage and screen. Trouble is, Jaffe is also a control freak who turns mentoring into manipulation. After three years Lily leaves – and Jaffe can’t get a hit without her. Smuggling his way onto the luxurious 20th Century Ltd express train from Chicago to New York, can Jaffe use the journey to win Lily back?

Hawks’ comedy is, along with It Happened One Night, one of the prototype screwball comedies. In some ways its even the best model. It has all the elements you expect: lightening fast dialogue, farcical set-ups, mistaken identities, ever more overblown rows, a dull second banana as the ‘new’ love interest, ludicrous misunderstandings and its heart a mismatched couple who get more of a thrill from fighting each other than they do from loving anyone else. You can see the roots for half the comedies that Hollywood produced over the next ten years here.

The film also captures the greatest screen performance by the leading actor of the American stage in the early years of the 20th century, John Barrymore. Barrymore’s performance is a delight –something near a self-parody – a larger-than-life role of bombast and wild-eyed eccentricity that should feel ridiculously over-blown, but actually really works. Jaffe is a force-of-nature, and that’s the performance Barrymore gives. He hurls himself into the fast-paced dialogue, delights in the physical comedy (from prat falls to swooning fits) and he gives the film most of its understanding of the mechanics of theatre (Hawks famously said he knew nothing about it). It’s a delightful, hilarious comic performance.

He’s well matched by a star-making turn from Carole Lombard, in one of her first roles. Initially overawed by working with Barrymore, Hawks coached Lombard to worry less about “acting” and to focus more on bringing her natural sharp-edged comedic instincts to the film. Something she does to huge success: you can feel the performance getting larger, wilder and more hysterically funny as the film goes on. By the time she’s half playfully, half furiously kicking at Barrymore’s stomach during one late argument in a train compartment, we’ve seen a brilliant comic actress find her stride. Lily goes from a talentless ingenue to a grand dame of stage and screen – but never loses (only conceals) her chippy rumbustiousness nature.

It’s all wrapped up in a neat parody of the artificial, overblown, performative nature of acting and theatrical types. These two are always putting on a show: either for themselves or for each other. Everything is filtered through their understanding of scripts and stories and their trade has made them artificial and unnatural people. If they feel larger-than-life, its because small intimacies don’t shift seats in the theatre. And the theatre is of course the real calling of an actor – not those shabby temptations of the big screen.

Not that the theatre is really that different. The film is book-ended by rehearsals for two almost identical Jaffe productions. Both of them are feeble Southern Belle dramas, with shock murders, deferential servants and stuffed with secrets and lies and plot reveals which could have been thrown together by chimps with typewriters. Between these, Jaffe stages a ghastly sounding Joan of Arc play and flirts with the most tasteless Life of Jesus play you could imagine (with an all-singing, all-dancing role for Lily as Mary). But then art seems to be less important than exhibitionism to these guys.

It’s not as if Jaffe’s style is designed to explore depth of character with his actors. For all his fine words in rehearsals, Jaffe is soon drawing chalk lines on the floor to tell Lily exactly where to stand on every line (the floor soon resembles a spider’s web of crossed lines and numbers) and finally gets the scream he wants from her in a scene by sticking a pin in her derriere. Lily is both infuriated and delighted by these methods – she keeps the pin as a treasured totem for years – but it’s clear acting is really an excuse for all the attention seeking screaming and shouting that they do anyway.

Twentieth Century makes for a neat little satire on the artificial nature of some acting, but at heart its mostly a very fast-paced, witty film that bottles two cracker-jack performers who engage in a game of one-up-manship to see who can deliver the wildest, hammiest and most entertaining line readings. Hawks directs with a confident assurance and the train-based finale (it does take nearly half the film to board the eponymous train) is a perfectly staged farcical comedy of entrances, exits and misunderstandings. The film itself is as theatrical as the personalities of its lead characters – and all the more delightful for it.