|

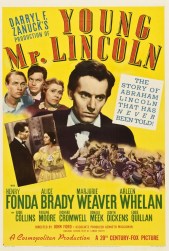

Henry Fonda excels in the origins story as the Young Mr Lincoln |

Director: John Ford

Cast: Henry Fonda (Abraham Lincoln), Alice Brady (Abigail Clay), Marjorie Weaver (Mary Todd), Arleen Weaver (Sarah Clay), Eddie Collins (Efe Turner), Pauline Moore (Ann Rutledge), Richard Cromwell (Matt Clay), Donald Meek (Prosecutor John Felder), Eddie Quillan (Adam Clay), Spencer Charters (Judge Herbert A Bell), Ward Bond (John Palmer Cass), Milburn Stone (Stephen A Douglas)

John Ford is often called the mythmaker of America, the director who perhaps contributed more than any other to building a romantic vision of America’s roots and past. As an explorer of the legends and mythology that underpinned his country, it’s perhaps no great surprise that he directed a film about the American revered more than any other since the Founding Fathers – Abraham Lincoln himself.

Playing out over 10 years, the film follows Young Honest Abe (Henry Fonda) from his days of autodidactism with a law book in Illinois, through his love for, and the death of, Ann Rutledge (Pauline Moore) and his arrival in Springfield to practice law (which he does with a shrewdness mixed with the wisdom of Solomon). The bulk of the film’s plot focuses in particular on him representing two brothers accused of murder in a courtroom trial, where Lincoln’s wit, wisdom and determination see justice done.

Okay reading that subplot, it’s pretty clear that this is a fairly rose-tinted view of The Great Emancipator. Henry Fonda had put off playing the role, as he felt it would be like hewing a performance out of marble. It’s hard for non-Americans to even begin to understand the reverence with which Lincoln is almost universally held in America, but it runs through this film like sugar through a stick of rock. Lincoln throughout the film is maybe an increasingly canny operator with a mastery of winning people over and playing crowds large and small, but he’s also always right, always does the right thing and always has a warm regard and love for genuine real people.

If you made the film today it would probably be called Abraham Lincoln: Origins, as Ford shows Lincoln building up all the weapons that would become central to his political artistry. Fonda starts the film gangly and physically awkward, finding it hard to know what to do with his height or long arms while giving speeches (Fonda wore platform shoes to increase his height). But even at the start his words are warm and genuine, even if his delivery is awkward. It’s something he masters to a far greater degree by the mid-way point of the film, when he skilfully diffuses a potential lynch mob with wit, gentleness, calm and a bit of righteous shaming. By the time he hits the courtroom, he’s overwhelmingly confident in his physicality and able to match it up with his oratorical brilliance and his skill at using seemingly rambling, inconsequential stories to suddenly hit home a sharp and painful truth.

Fonda’s impressive performance as Lincoln makes the film. Fonda gives Lincoln not just these positives but also hints at his sharpness of mind and his cunning. Negotiating a legal disagreement between two farmers (which he does with such skill that both end up paying him), he not only gives a fair sentence, but shows how he is not above manipulating men to achieve his ends (and, in biting one of the coins that he is given, that he may be honest himself but he’s not always trusting). He has a romantic regard for the mother of his clients (played very well by Alice Brady), but can still gently patronise her with his romantic ideal of her as an ideal American mother.

But when the push comes, Lincoln is a man of principle, wrapped in a skilful performance. The idea of mob justice is anathema to him, while Fonda makes clear he’s smart enough to not say that outright but to guide the crowd to agree with him. During the selection of the jury for the courtroom scene, he will accept men honest enough to say they favour hanging for the guilty, but turn down equivocators or those who believe they are better than the accused men. During the trial scene, he erupts in moral outage when the boys’ mother is pressured into naming one of her sons as the killer so as to save the other from the death penalty.

But he’s also a clever and brilliant player of the game, able to charm both the working classes and the rich, even if he’s not comfortable with either. During the trial scene, his quick wit and relaxation run rings around the government prosecutor (a good role of absolute convictions from Donald Meek) and he easily wins the crowd over with a series of gags and light touches that also carry with them a real, deep truth. Ford is also able to show his ambition – over the grave of Ann Rutledge he lets the fall of a stick decide whether he will continue his career or stay at home, and he all too clearly lets the stick lean over one way before letting it fall (he even acknowledges this himself).

Ford’s film is only very loosely based on actual true events – only the final coup Lincoln uses to win the case is really based on fact. The film is covered with smatterings of what look now like clumsy droppings in of key facts or persons from Lincoln’s life – from the cowpoke who plays “Dixie” (“Sounds like a song you could march to” is Lincoln’s comment) to Lincoln meeting future-wife Mary Todd, to his legal (and romantic) rival being none other than Stephen A Douglas his later rival for the presidency. There could have been a lot more, but afraid that it would make the film ridiculous, Ford kept these to a minimum by simply refusing to shoot them (such as a planned scene where Lincoln met John Wilkes Booth).

It all works because the audience knows who Lincoln will become, and it’s told with an earnestness and a certain amount of pace. Ford however really crafts a modern American myth and it even ends in a suitably epic scale: having won the case, Lincoln strikes off for a walk up a hill, trudging into the distance while a storm brews, heading onwards and upwards away from us and into his future. Sure it’s corn, but it works.