Odd choices are made in this Hugo adaptation, despite good photography and performances

Director: Richard Boleslawski

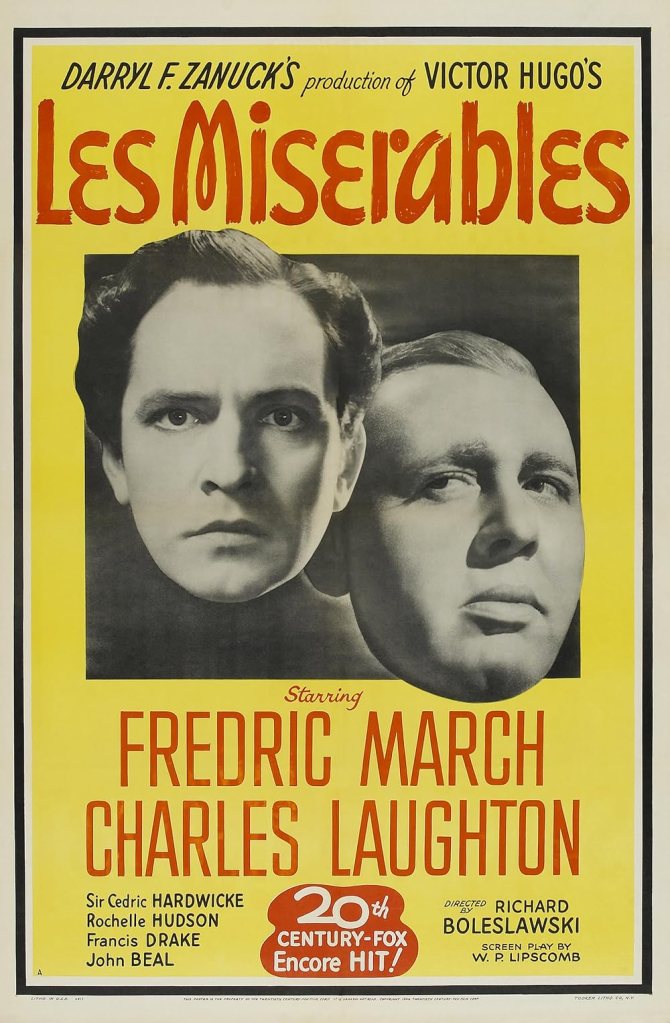

Cast: Fredric March (Jean Valjean), Charles Laughton (Inspector Javert), Cedric Hardwicke (Bishop Myriel), Rochelle Hudson (Cosette), Marilyn Knowlden (Young Cosette), Florence Eldridge (Fantine), John Beal (Marius), Frances Drake (Éponine), John Carradine (Enjolras)

There isn’t a more famous loaf of bread in literature, than that stolen by Jean Valjean to feed his starving family. There’s something quite sweet about the fact that Richard Boleslawski’s film of Hugo’s doorstop gives that loaf its moment in the sun, as its half-eaten remains are produced as evidence in Valjean’s trial. It’s an unintentionally funny moment, but feels right in a sometimes blunt film, that at times makes odd decisions for those of us so familiar now with the plot’s ins-and-outs and the moral up-righteousness of its lead character after forty years of the musical. Boleslawski’s version is an odd mix, part psychological drama, part atmospheric thriller, part thuddingly obvious soap where a loaf of bread needs to be literally seen. Parts of it work extremely well, other parts weigh the film down like the chains on its galley slaves.

The film is overwhelmingly focused on the clash between Valjean (Fredric March) and Javert (Charles Laughton). One a good man who wrestles with temptation, but follows the sprit of justice. The other a rigid fanatic, who sees the letter of the law as gospel and the rights and wrongs of a situation an irrelevance. First meeting when Valjean serves a decade as a slave at the oars in the galleys, their paths recross after a released Valjean has a road-to-Damascus moment after the intervention of a noble priest (Cedric Hardwicke). Reinventing himself as ‘Monsieur Madeleine”, he becomes mayor of a small town and protector of Fantine (Florence Eldredge) and her daughter Cosette (Rochelle Hudson). But he cannot escape the pursuit of Javert which carries him into hiding for years in Paris, where a now grown-up Cosette falls in love with reforming student Marius (John Beal), leaving Valjean with one last dangerous choice.

Les Misérables restructures the novel into three acts, each presenting Valjean with a moral quandary. As such, Fredric March’s impressive performance must be unique among Valjean’s: this version is forever tempted with greed, anger and his own desires, constantly struggling to overcome his baser feelings. March is very good at bringing to life this conflict, just as he sells the sense of awakening purpose Valjean feels washing over him after the Bishop’s intervention prevents him from being returned to prison. It’s a muscular, agonised performance of a man constantly striving, even in the face of his resentment, to live up to his adopted moral principles. So, much as Valjean would like to let another man be accidentally condemned for his crimes, or to keep Cosette to himself or pull a trigger on Javert (March’s skilfully communicating the deep internal conflict each time) he’ll still (however reluctantly) find himself doing the right thing.

He contrasts excellently, with Laughton’s rigid, well-spoken, self-loathing Javert who has absorbed his moral code so completely, its left no room for any other form of principle or emotional judgement. Introduced, lips quivering, as he explains being denied promotion due to his convict father, Laughton’s Javert has channelled that resentment to worshipping the penal code as God. As he repeats, several times, good or bad is irrelevant, it’s just about the law. Of course, Laughton’s performance bubbles with repressed frustration, his pursuit of Valjean clearly motivated by far more personal feelings of anger and envy than he is willing to admit. Valjean is a spoke in his wheel of justice, a factor that makes no sense to him.

Boleslawski’s film is at its best when these two face off. It’s also at its most stylistic for these sequences. Les Misérables is awash with Gregg Toland’s atmospheric, mist-filled photography and expertly uses his expressionistic shadows. It’s depiction of a Parisian uprising, just like it’s introduction of a fast-paced horse chase between Valjean and Javert, are snappily edited and throw in a parade of dynamic Dutch and high angles. At the end of each act, Christian imagery is well used (in two cases, shrines to Mary and Jesus) to add emotional heft. A pursuit through grime and mist-filled sewers near the film’s close has a Fritz Lang atmospheric strength (did Carol Reed watch this before The Third Man?) as well as the film’s most effective use of music to build atmosphere as Valjean desperately submerges himself and Marius to hide.

There is effective stuff in Les Misérables. So, you try your best to forgive the fact it’s full of extremely on-the-nose, obvious touches. The introduction of the bread at the trial is not an end of its obviousness: for starters, the galley’s were prison hulks, not actual ships rowed around by convicts (where do they imagine these enormous hulks are going?). Truncating so much of the book down – and focusing overwhelmingly on its two leads – means many other parts of the story are short-changed or make little impact or sense (the hilariously watered down Parisian revolutionaries don’t turn up until the final 40 minutes). Florence Eldridge’s Fantine (all references to her prostitution are of course cut) does almost nothing but die – although not before the film gives her a (unique) ludicrously sentimental reunion scene with her daughter (played by a highly irritating precocious film-school brat before she grows up into Rochelle Hudson). Clearly the actual tragedy here (a mother never sees her daughter again) was considered too much.

Then there are the strange mis-readings and mis-interpretations. I can understand why Marius and his law students are re-imagined, by conservative Hollywood, into legal reformers rather than idealisitic revolutionaries (Marius even denounces the very idea of overthrowing the government as terrible). Here they want only penal reform – although of course, while ensuring the guilty are harshly punished – and chat like champagne socialists. It’s a bit of a mystery why this call for slow-paced, moderate social reform erupts into throwing up barricades, but clearly audiences at the time couldn’t be expected to get on board with anti-Monarchist cells. They’d probably agree with Eponine (interpreted here as a sort of femme fatale and Marius’ secretary) that it’s all a silly, slightly disreputable, waste of time.

However, even more strange, is the inexplicable interpretation of Valjean’s desire to keep Cosette to himself not due to being a protective father-figure investing everything in his life into his daughter, but instead an unpleasant sexual desire to make Cosette his wife. Even leaving aside this utter perversion of the novel, since we’ve seen Valjean raise her from the age of about 6 it’s hard not to feel a bit of bile forming in your throat at the stench of grooming this gives the relationship. It’s almost as if Hollywood could only imagine a man going to great lengths to protect a woman if he wanted to eventually get in her pants.

It’s odd reinventions like this that don’t quite work even within the world presented by the adaptation, let alone compared to the original source, that weighs the film down too much. They are blotches in the streamlining of a huge novel. But when the film focuses on an increasingly personal clash between two men, both well played by March and Fredric, and its atmospheric visuals, it works much better.