|

Rosalind Russell and Cary Grant bicker and spar in His Girl Friday, one of the all-time classics I’ve never quite clicked with |

Director: Howard Hawks

Cast: Cary Grant (Walter Burns), Rosalind Russell (Hildy Johnson), Ralph Bellamy (Bruce Baldwin), Gene Lockhart (Sheriff Hartwell), Porter Hall (Murphy), Ernest Truex (Bensinger), Cliff Edwards (Endicott), Clarence Kolb (The Mayor), Roscoe Karns (McCue), Frank Jenks (Wilson), Regis Toomey (Sanders), Abner Biberman (Louie), Frank Orth (Duffy), John Qualen (Earl Williams), Helen Mack (Mollie Mallot)

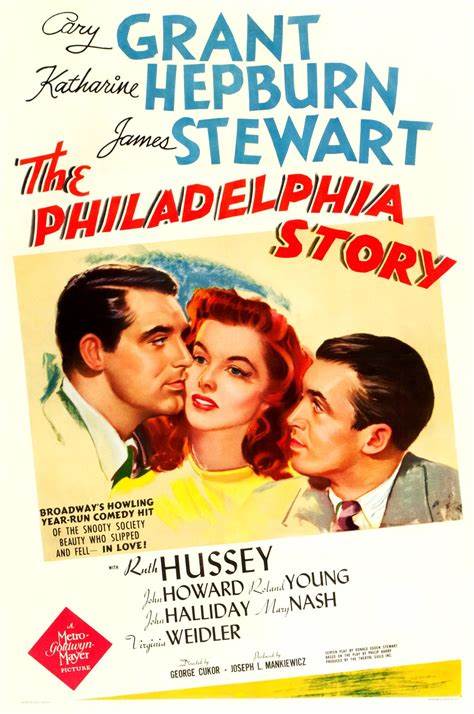

There’s always one film classic that the world and his dog love to bits, but every time you watch it you just don’t get it. That classic for me is His Girl Friday. I’m not sure many films have appeared more than this one on film buffs’ lists of Top Ten Movies of All Time, but while I admire its many, many qualities, every time I’ve watched it – and it’s at least three now – I just don’t love it. More to the point I don’t find it funny (I know, I know I can practically hear your jaws hitting the floor), neither do I engage with or root for its lead characters (please don’t hit me). I admire a lot of things about this film and how it is made. And I chuckle from time to time when I watch it. But for some reason even I’m not sure of, I’ve got no click with this film. Compared to The Awful Truth or The Lady Eve or The Philadelphia Story (all films this bears a lot of comparison with) I just don’t feel it.

It’s an adaptation of Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur’s play The Front Page. In quite a modern touch, one of its lead characters is gender flipped. In the play, a newspaper editor tries to persuade his star reporter not to quit the game: in His Girl Friday the star reporter not only becomes a woman but, don’t you know it, the ex-wife of the editor, about to walk out (in more ways than one) to marry her dull fiancé. Cary Grant (who else?) is the fast-talking editor Walter Burns, Rosalind Russell the fast-talking star reporter Hildy Johnson. In fact, everyone is fast-talking, in the film that holds the world record for dialogue speed. Can Burns persuade Hildy to hold off leaving with fiancée Bruce Baldwin (Ralph Bellamy – sportingly playing up to his dull reputation) for one more day so she can cover the story of strangely naïve convict Earl Williams (John Qualen)? Let the madness ensue.

Let’s focus on all the good stuff first. Not least because my general lack of connection to a film loved by all and sundry is so personal, it almost defies analysis. Hawks was, rumour has it, won round to the idea of gender-swapping Hildy by hosting a read-through of the play at a dinner party with a shortage of people, meaning Hildy was read by a woman. That opened up a host of ideas around combining this with the classic re-marriage genre and bang away we go. It is, needless to say, a brilliant idea and adds such a spark to every single interaction between the two characters that it distinctly improves the play (later productions have often carried the idea – and the dialogue – across from this film).

On top of this, Hawks wanted to make this the fastest talking comedy film ever made. And boy does he succeed at that. The dialogue of this film is delivered with such rat-a-tat speed that clock watchers report it hits a rate of over 300 words a minute (try reading that many words out in one minute to see how fast that is). It gives the film a ferocious manic energy and thunder-cracker momentum and keeps the punchlines coming fast. It also needs gifted actors, which it sure-as-hell gets here. Grant possibly hits his comedic peak here, managing to still remain suave, cool and collected, even as he’s ripping through words and shifting verbal goalposts at dazzling speed. This is also Russell’s career highlight, embodying the image of the sort of spunky, arch and no-nonsense professional woman of screwball comedy that all others (even Hepburn) are measured against.

They race through a film that makes excellent use of long-takes, intelligent single-shot camera moves and careful, intelligent editing to highlight the electric speed of the zany dialogue. In particular, Hawks makes a brilliant motif of telephones (those old candlestick phones), which characters are forever hurling instructions down, using as escape tools from awkward moments and juggling conversations with (either from multiple phones or between the phone and people in the room). They are used for short, sharp, punchy lines – and it fits a film that is all momentum and short-hand. The ultra-smart, quotable banter, littered with one-liners, is the ultimate epitome of the popular style of dialogue at the time, which favoured this style over the speeches and deeper content that was seen as more of the preserve of theatre.

Walter and Hildy in this version also become the epitome of “the screwball couple”. The divorced partners who of course still love each other, largely because they recognise that no-one else will share their insane energy and obsession. Not to mention that fighting and feuding with their intellectual equal is a million times sexier (and better foreplay) than a thousand dinners at home with someone average will ever be. Ralph Bellamy does good work here (essentially, like Grant, repeating his role from The Awful Truth) as that dull, trusting man – the only one in the film who vaguely resembles a human being and therefore, obviously, the character the audience likes the least (who goes to the cinema to see someone like themselves on the screen, eh?)

There is so much right about His Girl Friday. The actors are sublime, the dialogue delivered perfectly, Hawks’ direction is pin-point in its mix of old-Hollywood classicism, and it’s very well shot. So why don’t I like it more? It’s that most personal feeling: I just don’t find it funny enough. Maybe that’s because I need to connect with characters more – and I don’t connect with Hildy and Walter. In some ways I don’t even like them. His Girl Friday is frequently an unapologetically cruel film: Hildy and Walter treat several people like crap, largely for their own amusement or as collateral damage in their own war of foreplay. At one point a desperate, lonely woman attempts suicide (she jumps out of a damn window falling a couple of floors) – Hildy and Walter are joking about it in seconds. They are cold, self-obsessed people and for all their superficial charm, there isn’t any touch of warmth to them at all. They are very artificial people in an artificial world. In all, I don’t really like them and I find it hard to careor want them back together (other than recognising that they deserve each other).

Believe me, I understand some comedy is cruel, I don’t have a problem with that. But I don’t think His Girl Friday realises it’s that kind of film. The Awful Truth has a very similar plot – but that had its characters recognise their own faults and also gave us reasons to care for them as human beings. His Girl Friday doesn’t do either of those things, meaning I laughed a lot in The Awful Truth and not so much in His Girl Friday.

Can you still bear to read on after such blasphemy? But there you go. Everyone has that stone-cold classic that they just can’t get on board with. This film is mine. I respect so much about it, but it neither tickles my funny bone nor makes me feel welcomed. I find it a cold and cruelly minded film, that looks down on people with scorn – from Bruce to criminal Earl Williams and most especially to his distraught girlfriend Molly – and invites us to do the same. It wants us to love the popular kids in the class and join them in spitting paper balls at the losers. This doesn’t do it for me. I know everyone loves it. Hell, I know I’m probably wrong. But I just don’t love His Girl Friday.