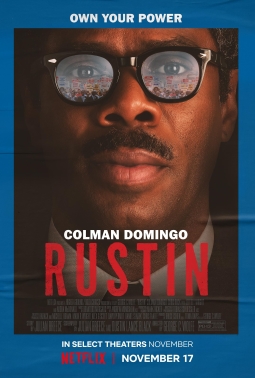

Solid biopic tells an inspiring story in a straightforward way with a Domingo star turn

Director: George C Wolfe

Cast: Colman Domingo (Bayard Rustin), Aml Ameen (Martin Luther King Jnr), Glynn Turman (A Philip Randolph), Chris Rock (Roy Wilkins), Gus Halper (Tom Kahn), Johnny Ramey (Elias Taylor), CCH Pounder (Dr Anna Hedgeman), Michael Potts (Cleve Robinson), Audra McDonald (Ella Baker), Jeffrey Wright (Adam Clayton Powell Jnr), Lilli Kay (Rachell), Jordan-Amanda Hall (Charlene), Bill Irwin (AJ Muste)

Bayard Rustin was on of crucial the civil rights activists in conceiving, planning and organising the 1963 March on Washington. A proponent of nonviolence and equal rights for all, regardless of race, gender or sexuality, he was a close friend and colleague of Martin Luther King and a key figure in innumerable campaigns. Rustin partly exists to bring his life more to public notice, focusing on the build-up to the March on Washington and exploring Rustin’s struggles as both a Black man and a gay man.

At its heart is Colman Domingo, who delivers a sensational performance as Rustin, bursting with energy and emotional compassion. Domingo brilliantly captures Rustin’s loud-and-proud nature, his overwhelming commitment to being who he is, and his passionate commitment to social justice. This is a force-of-nature turn dominating the movie, breathing passion and fire into Rustin’s compulsive desire to speak out.

Domingo matches this with a neat sense of comic timing (Rustin is frequently very funny) and a raw emotion. The emotional impact nearly all comes from Domingo. He’s genuinely moving when he misjudges the level of loyalty to him in the film’s opening act and has an offer of resignation accepted by the NAACP (after press reports suggesting he has seduced King). Even more so later in his emotional outpouring when the same NAACP members finally back him up. More focus on Rustin gaining full, unquestioning, acceptance from his colleagues could have offered a beating heart to the film.

Domingo’s performance elevates an otherwise, to be honest, fairly middle-of-the-road biopic that frequently wears its research heavily. It has an air of competent professionalism, with George C Wolfe’s direction lacking emotional or visual spark. Much of the dialogue – given a brush by Dustin Lance Black – frequently (and rather painfully) has the actors fill in historical context or clumsily shoehorns in real dialogue. There is very little spark to Rustin, as it dutifully ticks off events, building towards sign-posted emotional payoffs (and, admittedly, there are fewer payoffs more inspiring than a quarter of a million people gathering in Washington to cry for freedom).

This is not to say there aren’t fine moments and its recreation of the Washington March (some tight angles, well-chosen archive footage and subtle effects) works very well. There are some fine actors giving their all. Glynn Turman is a stand-out as the inspiring Randolph, savvy enough to play the game in a way Rustin isn’t. Aml Ameen’s capturing of King’s voice and mannerisms is perfect. Pounder, Rock, McDonald and others compellingly bring to life leading activists while Jeffrey Wright sportingly plays the closest thing to a heel as jealous congressman Clayton Powell.

However skilful reconstructions only take us so far. Often personal stakes are presented vaguely. The film avoids depicting Rustin encountering much personal homophobia – no member of the movement expresses negative views, with white pacifist campaigner AJ Muste (Bill Irwin) the only person to express openly homophobic opinions. The threat of someone discovering his past arrest (for a 1953 encounter with two men in Pasadena) is played as a core fear for Rustin, but the film is vague about the likely impact this revelation would have (since it seems to already be widely know). It’s astonishing that Rustin was so open when being so was a crime, but the film (aside from a brief moment when he considers a casual pick-up) risks underplaying the era’s prejudice and dangers.

To cover issues on homophobia and self-loathing guilt, the film invents a closeted reverend, well played with a tortured sense of shame and self-loathing by Johnny Ramey, who initiates a secretive relationship with Rustin. This fictional character absorbs all the fear and self-denial that many gay people felt at the time, allowing Rustin to show us what life was like for the many, many people who, for whatever reason, were not as outspoken as Rustin. But it does feel like somewhat of a compromise, and a character who feels a little too convenient, drifting to and from the story whenever it’s themes need a bit more of a personal touch.

It’s hard not to think the film could have gained more interest from exploring Rustin’s relationship with Tom Kahn (Gus Halper) – or even being clearer on the very nature of this relationship. An initial familiar intimacy indicates an established romantic relationship, but later scenes suggest instead a more casual flatmates-with-benefits set-up. Then we suddenly hit the inevitable moment when Kahn walks in on Rustin and Elias kissing and reacts like a betrayed partner. It finally decides Kahn is in love with Rustin, but Rustin hasn’t time for a relationship with so much work to be done. Despite this thought, the film wants to also say Rustin and Elias are profoundly in love, tragically only kept apart by social pressures. It’s trying to have its cake and eat it too. The cost to your personal life of being fully committed to a cause, or the awful pressures of loving someone in the face of prejudice, are both powerful stories. Settling on one and exploring it fully would have been more emotionally rewarding.

Rustin is a solid, well-handled, decent biopic. Bringing the life of a lesser-known civil rights activist to a bigger audience is a worthy aim, and Black and queer audiences (historically underserved) deserve to see films that centre their stories. It’s also refreshing to see a film zero in on the importance of logistics for major events (what other film has a scene where the fillings of thousands of sandwiches to be kept in the warm sunshine becomes a heated debate?) and its focus on the work recruiting attendees, buses and resources for the March is great.

But the real success in this sometimes workmanlike film is Domingo, who lifts the entire thing with an emotionally committed performance that is perhaps better than it deserves.