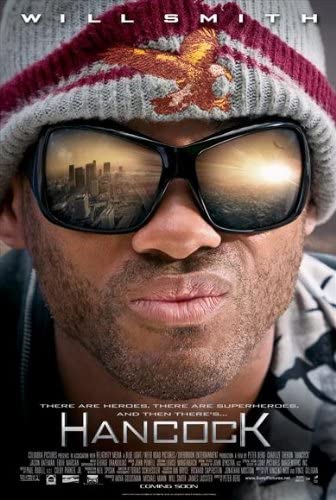

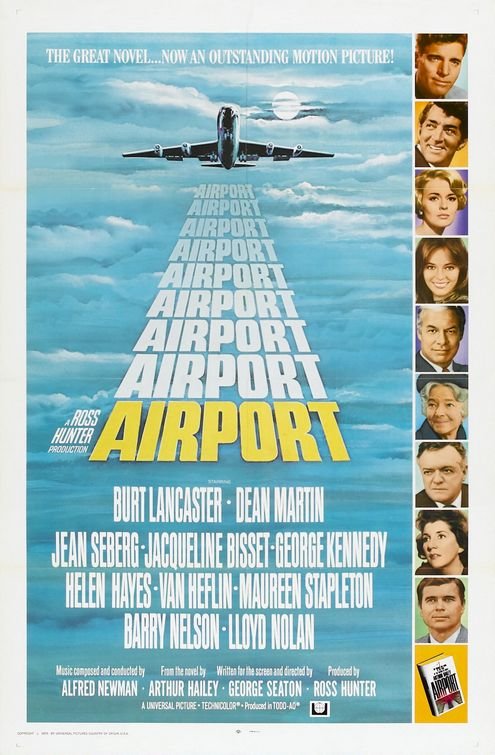

Disaster awaits in the sky in this ridiculous soap that is less exciting than Airplane!

Director: George Seaton

Cast: Burt Lancaster (Mel Bakersfied), Dean Martin (Captain Vernon Demerest), Jean Seberg (Tanya Livingston), Jacqueline Bisset (Gwen Meighen), George Kennedy (Joe Patroni), Helen Hayes (Ada Quonsett), Van Heflin (DO Guerrero), Maureen Stapleton (Inez Guerrero), Barry Nelson (Captain Anson Harris), Dana Wynter (Cindy Bakersfeld), Lloyd Nolan (Harry Standish), Barbara Hale (Sarah Demarest), Gary Collins (Cy Jordan)

A busy Chicago airport in the middle of a snowstorm. Workaholic Mel Bakersfeld (Burt Lancaster) doesn’t have time to prop up his failing marriage to his humourless wife: he’s got to keep the flights moving, clear the runways and solve the problems other people can’t. He’s not dissimilar to his brother-in-law Vernon Demerest (Dean Martin), who hasn’t got time for his plain-Jane wife at home when he’s got a flight to Rome to run and a saintly pregnant air hostess girlfriend Gwen (Jacqueline Bisset), to deal with. Tensions will come to a head when depressed former construction worker Guerrero (Van Heflin) joins Demerest’s flight, planning to blow himself up so his wife can profit from his life insurance. Disaster awaits!

“A piece of junk”. That was Burt Lancaster’s pithy review of this box-office smash that was garlanded with no fewer than ten Oscar nominations. He’s pretty much spot on. Airport is a dreadful picture, a puffed-up, wooden soap opera that never takes flight, stapled together with a brief disaster plotline that only really kicks in during the final act of the film and is solved with relative ease. Other than that, it’s all hands to the pumps to coat the film in soapy suds, which can be stirred up by the strips of wooden dialogue that fall from the actors’ mouths.

Seaton adapted the script from a popular low-brow novel, though it feels as if precious little effort went into it. It’s corny, predictable dialogue does very little to freshen up the bog-standard domestic drama we’re watching in a novel setting. Both lead actors juggle loveless marriages with far prettier (and much younger) girlfriends. Those girlfriends – Jean Seberg for Burt and Jacqueline Bisset for Dean – play thankless roles, happily accepting of their place as no more than a potential bit-on-the-side and very respectful of the fact that the job damn it is the most important thing.

The film bends over backwards so that we find Burt and Dean admirable, despite the fact that objectively their behaviour is awful. Burt treats his home like a stopover, barely sees his kids and seems affronted that his wife objects he doesn’t attend her important charity functions and doesn’t want the cushy job he’s being offered by her father. Just in case we sympathise with her, she’s a cold, frigid, mean and demanding shrew who – just to put the tin lid on it – is carrying on behind Burt’s back. We, meanwhile, applaud Burt for showing restraint around the besotted Jean Seberg, merely kissing, hugging and chatting with her about how he’d love to but he can’t because of the kids at home damn it!

He looks like a prince though compared to Dean. Only in the 1970s surely would we be expected to find it admirable that a pregnant girlfriend happily takes all the blame – the contraceptive pills made her fat and she knows the deal – begs her boyfriend not to leave his wife and then urges him to not worry about her. Dean’s wife doesn’t even seem that bad, other than the fact she’s a mumsy type who can’t hold a candle to Bisset’s sensuality. That sensuality is overpowering for Dean, who at one point pleads with her to stay in their hotel room because the taxi “can wait another 15 minutes”. Like a gentleman his reaction to finding out Bisset is pregnant, is to offer to fly her to Norway for a classy abortion (rather than the backstreet offerings at home?).

This soapy nonsense, with its stink of Mad Men-ish sexual politics (where men are hard-working, hard-playing types, and women accept that when they age out, he has the right to look elsewhere) is counterbalanced by some laboriously-pleased-with-itself looks at airport operations. Baggage handling. Customer check-in. Customs control checks. Airport maintenance. All get trotted through with a curious eye by Seaton. Just enough to make parts of the film feel briefly like a dull fly-on-the-wall drama rather than a turgid soap.

Soap is where its heart is though. Helen Hayes won an Oscar for a crowd-pleasing turn (from which she wrings the maximum amount of charm) as a seemingly sweet old woman who is in fact an expert stowaway. Van Heflin and Maureen Stapleton play with maximum commitment (Stapleton in particular goes for it as if this was an O’Neil play rather than trash) a married couple whose finances are in the doldrums, leading the husband to take drastic steps.

It’s all marshalled together with a personality-free lack of pizzaz by Seaton, who simply points the camera and lets the actors go through their paces, with a few shots of humour here and there. There are some interesting split-screen effects, but that’s about the last touch of invention in the piece. It’s mostly played with po-faced seriousness – something that feels almost impossible to take seriously today, seeing as the structure, tone and airport observational style of the film was spoofed so successfully in Airplane (a much better film than this on every single level, from humour, to drama even to tension – how damning is that, that a pisstake is a more exciting disaster thriller?)

It smashed the box office in 1970 and got nominated for Best Picture. But its dryness, dullness and lack of pace mean it has hardly been watched since. Although it can claim to be the first all-star disaster movie, it’s not even fit to lace the flippers of The Poseidon Adventure, which far more successfully kickstarted the cliches that would become standard for the genre (and is a tonne more fun as well as being a disaster movie – this has a disaster epilogue at best). An overlong, soapy, dull mess.