Reverent adaptation of the most famous diary ever written, that drains it of any sense of life or drama

Director: George Stevens

Cast: Millie Perkins (Anne Frank), Joseph Schildkaut (Otto Frank), Shelley Winters (Petronella Van Daan), Richard Beymer (Peter Van Daan), Gusti Huber (Edith Frank), Lou Jacobi (Hans Van Daan), Diane Baker (Margot Frank), Ed Wynn (Albert Dussell), Douglas Spencer (Kraler), Dodie Heath (Miep Gies)

Few personal stories have had such a huge impact on so many people’s lives than Anne Frank’s diary. This literary marvel, written by a teenager who mixed profound insight with teenage obsessions, was a world-wide sensation when it was published after the war. The diary covers the over two years Anne, her family and their friends spent in hiding in a secret annexe in her father’s warehouse in Amsterdam. For Jews hiding from the barbaric persecution of the Nazi occupying forces, every day was a struggle between trying to lead as normal a life as possible and the terror of discovery and deportation to a concentration camp. Of course, we know, tragically, they were discovered – and only Anne’s father Otto survived the war.

Otto discovered the diary when he returned to Amsterdam after the liberation of Auschwitz. Moved by the diary’s mix of maturity and youth, Otto had it published first for friends and then more widely. At various points, parts of the diary were edited to remove more “personal” content (Anne wrote freely at points on her growing sexuality and was sometimes less than kind to the other occupants of the annexe). More modern editions have embraced a less edited, fuller diary that really allows us to see what a brilliant, challenging, sometimes judgemental, fully rounded teenager Anne was. The Diary of Anne Frank hails from an era that framed a more sanitised diary. The worst you can say for it is that I think there is a good chance the real Anne Frank would have found it a bit dull.

Adapted from a Pulitzer Prize winning play by Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett, George Steven’s film is reverent, noble and very worthy. It also frequently lacks any pace or life, and is so concerned with being life-affirming that it filters out nearly all sense of tension or conflict that these eight people felt (which they often did living, as they did, in a few small rooms for over two years, with very little food). The film also centres a romantic relationship between Anne and Peter – one that, according to Anne’s own diary, was already coming to an end at their discovery (in reality, she felt they had little in common other than living in the annexe together).

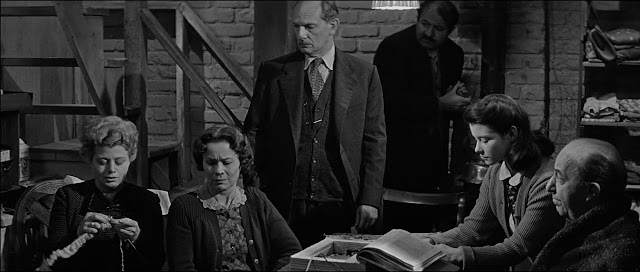

But Stevens’ film is so concerned with framing someone as fascinating as Anne as a secular saint that it removes much of the vibrancy that gives the diary such impact. It also doesn’t help that Stevens shoots the film in a luscious black-and-white, in detailed sets – but also in the widest possible cinemascope. This does allow for some lovely shots – an image of Anne and Peter kissing in a monochrome shadow, before a door opens to bathe them in light is striking – but it sacrifices the most essential fact of the setting: its cramped smallness.

|

The widescreen frequently makes the annexe seem larger than it is |

Who decided that a location defined by its claustrophobia and smallness was best captured in super-widescreen, I don’t know. But the wide angles make the annexe look a heck of a lot larger than it actually is (I’ve been there, I know it was more cramped than this!) and Stevens frequently frames the whole cast in shots which makes the annexe look positively cavernous.

The lack of claustrophobia has a serious impact on the story’s sense of drama. It also helps to filter out the tension. The script removes, or minimises, most of the key personal tensions in the annexe. We have moments of disagreement, but generally the inhabitants are shown to get on extremely well, with Anne herself practically perfect. This doesn’t really square with the diary, which is pretty open in Anne’s difficult relationship with her mother (with whom she felt no affinity), the clashes with the Van Daans and Mr Dussell (not their real names – Dussell basically translates as idiot, which gives a better impression of Anne’s difficult relationship with this unwanted roommate) or her later arguments with her father. Instead, things are smoothed out and nothing that could detract for a moment from the optimistic and hopeful message of the film is allowed.

The film also replicates several changes that the play made for dramatic effect. This most especially affects the character of Dussell (real name Fritz Pfeffer). In real life a respected dentist and pillar of the Jewish community, Dussell/Pfeffer here is a complacent, panicking imbecile, utterly ignorant of the Jewish faith and claims to have lived his whole life in Amsterdam with no idea he was a Jew. The real-life Pfeffer had in fact fled Germany to escape Nazi persecution. Played with a self-satisfied whininess by Ed Wynn (a famous TV comic, Oscar-nominated here for showing he could do drama), Dussell/Pfeffer is a joke. Pfeffer’s family cut ties with the Franks after the play was released.

Wynn’s nomination reflects how the broader performances in this film gained the most attention. Shelley Winters won an Oscar for her role as the blowsy Mrs van Daan – both van Daans are larger-than-life and obsessed with their status. More restrained and effective performances come from Gusti Huber as Anne’s shy and nervous mother and above all by Joseph Schildkraut as her wisely patient father. Richard Beymer gives an effective performance as a young Peter, straining against the leash of being stuck in a sort of suspended childhood.

As Anne, Millie Perkins looks the part in many ways – apart from the fact she is clearly too old. But there is something a little neutered and frankly a little too perfect about her performance. Her voice has a flat American twang to it that makes much of her voiceover a little wearing to listen to, especially as the tweeness is dialled up. I’m not sure she has the presence for the role – although she is not helped by the sanitised, earnest script.

Criticising The Diary of Anne Frank feels almost sacrilegious, like criticising the lives of the real people who went through something unimaginable to try and survive in a world of horror. But Stevens’ film is straining so hard to be reverent – and shaves the edges of its characters so much – that it turns them and their story into something much more easily digestible than it should be. It becomes a feelgood story, rather than something vibrant and alive. And that vibrancy is what has made Anne Frank live for so long after her murder. To create a film that captures so little of that, instead turning her into a conventional romantic heroine, just feels like it misses what made her unique.