Bold, beautiful and brilliant Skyfall is probably my favourite Bond film ever – sorry folks!

Director: Sam Mendes

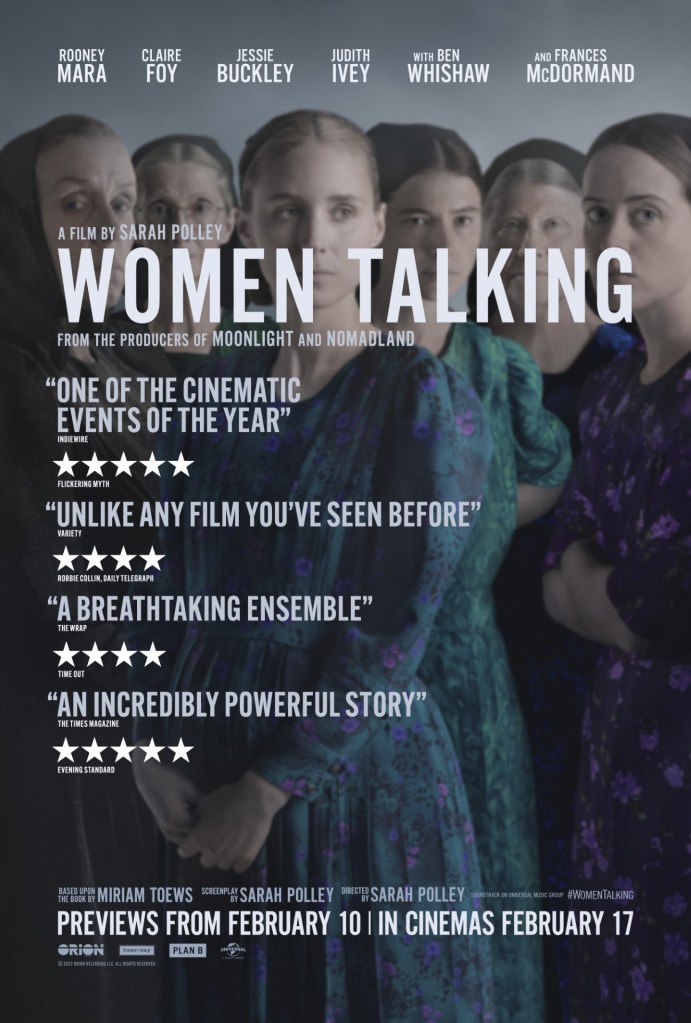

Cast: Daniel Craig (James Bond), Judi Dench (M), Javier Bardem (Raoul Silva), Ralph Fiennes (Gareth Mallory), Naomie Harris (Eve), Bérénice Marlohe (Sévérine), Albert Finney (Kincade), Ben Whishaw (Q), Rory Kinnear (Bill Tanner), Ola Rapace (Patrice), Helen McCrory (Clair Dowar MP)

As I watched Skyfall for the umpteenth time it suddenly occurred to me. I know I should say Goldfinger but I think this might just be both my favourite and the best James Bond film ever made. Released to coincide with the fifth anniversary of Doctor No, Skyfall manages to be an anniversary treat the celebrates Bond not with an ocean of call-backs but by telling a gripping story which plays to the star’s strengths and riffs imaginatively in both a literal and a metaphorical sense with our understanding of the legacy of the world’s best-known secret agent.

After a mission gone wrong leaves a list of undercover agents out in the open and Bond (Daniel Craig) presumed dead, MI6 comes under fire from a secret assailant seemingly determined to destroy the reputation of M (Judi Dench). With M already hanging on by a thread after that disastrous mission – Chairman of the JIC Gareth Mallory (Ralph Fiennes) is threatening her with removal – she has no choice but to lure Bond out of hiding and back into the spy game. But is the slightly out-of-shape, wounded spy ready for the challenge? The trial to find their mysterious enemy leads to Shanghai, Macau and the secretive island home of Raoul Silva (Javier Bardem), a Bond-like former British agent with a vendetta against M. Cure a battle of wits and wills between ‘these two last rats standing’.

Skyfall pretty much does everything right. Directed with verve, energy, intelligence and wit by Sam Mendes at the top of his game (Skyfall restored him to the front rank of British film directors), it mixes sensational action with well-acted, equally exciting character beats. It gets the balance exactly right – in the way that Quantum of Solace failed – between giving you the thrills but also really investing you in the drama. And it builds towards a final face-off that is, almost uniquely in the series, small-scale, intimate and personal (admittedly via a conflagration that consumes an ancestral Scottish castle and most of the Highlands). There is so much to enjoy here that you’d have to have a heart of stone not to be entertained. No wonder it’s the franchises biggest hit.

Mendes was brought on board at the suggestion (and persuasion) of Craig, eager to work with directors who would be recognise character was at least as important as fast cars and explosions, but also had the skill to deliver both. Skyfall is perfectly constructed to play to Craig’s strengths. His Bond reaches its zenith, a world-weary cynic with a strong vein of sarcasm, covering up deeply repressed unreconciled trauma. Craig is wonderful at conveying this under a naughty-boy grin.

Skyfall dials down the romance, Craig’s weakest string – it’s the only film in the franchise with no Bond girl (after QoS where, for the first time, Bond didn’t sleep with the Bond girl). Aside from a brief fling (with a character who is, perhaps a little tastelessly, all to dispensable – the fate of Sévérine being fudged with an uncomfortable flippancy) it’s Judi Dench who is the really ‘Bond Girl’ here. Judi Dench is fabulous in her swan-song, from taking the tough calls, voicing small regrets and quoting Tennyson. Skyfall acknowledges the surrogate parent relationship between M and Bond, something that was there from the day of Connery – every M has always inspired a filial loyalty from their 007. It’s a loyalty Skyfall reveals M ruthlessly exploits, extracting personal dedication from a host of agents, including both Bond and Silva – a man who (only half-jokingly) repeatedly calls her “Mummy” and has redefined his life around taking revenge on her.

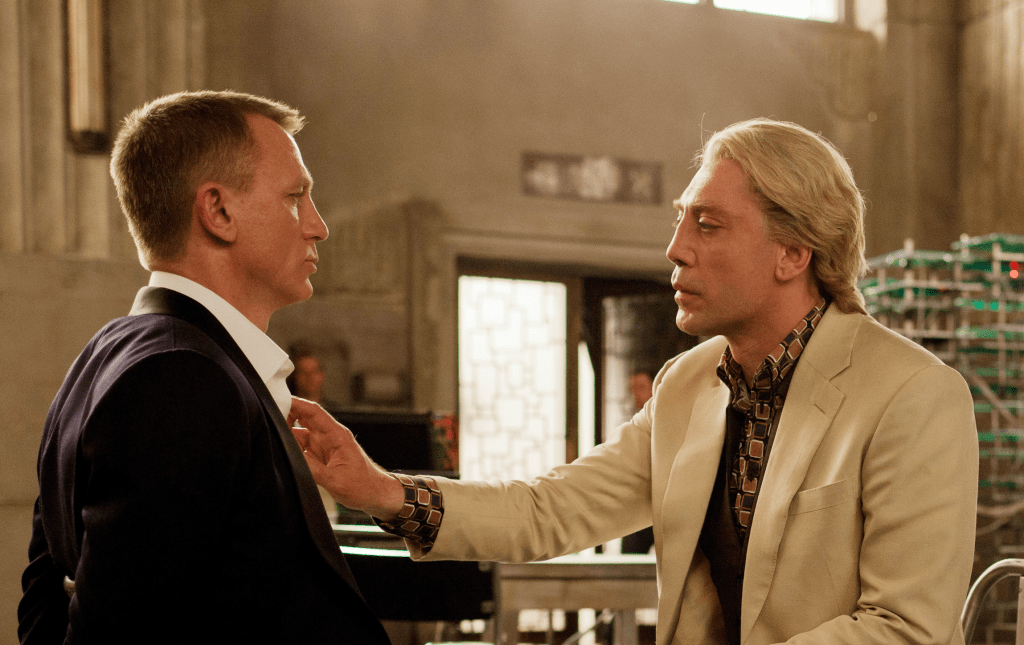

It makes a gift of a part for Javier Bardem, channelling his eccentricity into a character who often yings when he should yang. When he’s angry he laughs, when he’s overjoyed he gets quieter. Softly-spoken, almost effeminate, he’s also a ruthless killer – his studied manner of unpredictability a superb reflection of Bond’s own tightly constructed personality. Even their first meeting together is unusual and different – far from threatening Bond, Silva seems intent on seducing him, batting his eyes, stroking his bare chest with a finger and all but inviting him for a quickie (Bond’s classic response – “What makes you think this is my first time?” surely launched a thousand slash fictions).

There is a fabulously, just-below-the-line meta slice of fun going on in Skyfall. It brings Bond back from the dead (after its pulsating opening scene ends with him falling lifelessly to a watery grave), but burdens him with a host of scars. In a series of MI6 tests he completely misses a target, collapses to the floor after a workout, blows a psychological test and is repeatedly told he’s a borderline alcoholic. (In case we miss the point, Q meets him in front of Turner’s Fighting Temeraire and pointedly comments on the over-the-hill wreck being dragged back to port). Back in the field, his gunshot wounded shoulder gives out while holding onto the underside of a rising lift and Silva asks the question we’ve all asked at time or another: Mr Bond hasn’t it all gone on long enough?

While it can seem odd that two films ago Craig was introduced as a fresh-faced youngster and now embodies all fifty years of franchise ‘mileage’, it doesn’t really matter since he so triumphantly (of course!) reasserts his relevance. It’s a lovely, not too heavy-handed, piece of meta-commentary I think is both funny and human. It also means most of the call-backs to the gloried past of the franchise are metaphorical rather than literal – making a huge change from the Easter Egg stuffed nonsense you get from other franchises. It also means the one major piece of fanservice – the return of the Goldfinger car (the film is hilariously vague on whether this means Craig’s Bond and Connery’s Bond are one-and-the-same, a thing that really annoys some people who should really get a life) – really lands with a punch-the-air delight.

Skyfall is similarly astute with its characters. When Ralph Fiennes’ Gareth Mallory is introduced, we take him for an obstructive bureaucrat, flying his desk. Each scene in Fiennes’ perfectly pitched performance peels away layers to reveal a hardened professional (a decorated Army Colonel no less) and ally. It’s hard not to cheer when he takes up arms during Silva’s attack on a Parliamentary committee (with a gunshot wound no less) just as it’s hilarious to see Bond teasingly wink at Mallory before shooting out a fire extinguisher right next to him. Q returns, embodied by a perfectly cast Ben Whishaw, as a computer genius (in another gag at the franchise he’s scornful of ‘exploding pens’ and such like gadgets). Naomi Harris is very good as (it’s probably not a surprise any more to say) a Miss Moneypenny who’s a field agent in her own right. Skyfall even cheekily serves as a sort of back-door ‘origins’ story, leaving us with a very Fleming-Universal-Exports set-up.

It throws this all together with some sensational action scenes. The opening sequence is one of the best in the series, a manic chase through Istanbul that starts on foot in a darkened room (a nice reminder of M’s ruthlessness that she orders Bond to abandon to his certain death an injured agent) cars, bikes on rooftops, trains, diggers on trains and train rooftops (via a witty cufflink adjustment). There is a gorgeously shot fight-scene in a Shanghai rooftop (Roger Deakins pretty much makes Skyfall the most beautiful looking Bond film there has ever been) and a pulsating (and very witty) chase through the London Underground before that gripping Parliamentary committee gunfight. Mendes mixes excitement with plenty of neat jokes throughout and it works a treat – and the film plummets along at such speed you can forgive the little nits you can pick (like how does Silva know where to plant a bomb on the underground eh? And why did that train have no passengers?).

It culminates in a Home Alone inspired booby-trap rigged house in Scotland (wisely a Sean Connery cameo idea was nixed, with the legendary Albert Finney cast instead) and an Oedipal confrontation in a tiny Highlands church. At the end, it gave us thrills while bringing Bond home (in every sense) and was brave enough to focus on excellent actors play in a human story of regret, loss and betrayal. It’s a film which positively delighted me in the cinema and hasn’t stopped thrilling me the innumerable times I’ve seen it since then. And I can’t imagine it won’t continue to do so!