|

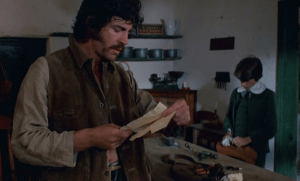

Michael Caine and Stanley Baker are under siege in classic Zulu |

Director: Cy Endfield

Cast: Stanley Baker (Lt John Chard), Michael Caine (Lt Gonville Bromhead), Jack Hawkins (Reverend Otto Witt), Ulla Jacobsson (Margareta Witt), James Booth (Pvt Henry Hook), Nigel Green (Colour Sgt Frank Bourne), Patrick Magee (Surgeon Major James Reynolds), Ivor Emmanuel (Pvt Owen), Paul Daneman (Sgt Robert Maxfield), Glynn Edwards (Cpl William Allen), Neil McCarthy (Pvt Thomas), David Kernan (Pvt Fredrick Hitch)

There are some films so well-known you only need to see a frame of them paused on a television to know instantly what it is. Zulu is one of those, instantly recognisable and impossible to switch off. A few notes of John Barry’s brilliant film score and you are sucked in. Zulu has been so popular for so long, it’s almost immune to any criticism, and deservedly so because it’s pretty much brilliant.

The film covers the battle of Rorke’s Drift in the Zulu War of 1879. Rorke’s Drift was a small missionary supply station, near the border of Zululand with the Transvaal. The British had instigated the Zulu war with a series of impossible-to-meet ultimatums (the Natal government wanted to restructure Southern Africa into a new confederation of British governed states and Zululand was in its way). The British had of course massively underestimated the disciplined, dedicated and organised Zulu armies and the war started with a catastrophic defeat of the British (nearly 1,500 killed) at Isandlwana by an army of 20,000 Zulu (who lost nearly 2,500 killed themselves). Isandlwana took place on the morning of the 22nd January – and by the afternoon nearly 4,000 Zulus had marched to Rorke’s Drift, garrisoned by 140 British soldiers.

The film opens with the aftermath of the Isandlwana defeat (with a voiceover by Richard Burton, reading the report of the disaster written by British commander Lord Chelmsford). The camera tracks over the bodies of the British, as the Zulu warriors move through the camp (the film omits the Zulu practice of mutilating the bodies of their fallen opponents, which is just as well). Action then transfers immediately to Rorke’s Drift where Lt John Chard (Stanley Baker), a Royal Engineer temporarily assigned to the base to build a bridge, is senior officer by a matter of months over Lt Gonville Bromhead (Michael Caine – famously billed as “Introducing Michael Caine”). Chard takes command of the preparations to repel the siege, building fortifications, arming the walking wounded, and carefully making the defensive line as tight as possible to cancel out the Zulu numbers (the exact opposite of what happened in Isandlwana).

Zulu is drama, not history. Much has been changed to make for better drama. Chard and Bromhead were not as divided along class lines. Nigel Green (excellent) plays Colour Sergeant Bourne exactly as we would expect a Colour Sergeant to appear – a tall, coolly reassuring martinet “father to his men” – so it’s a surprise to learn the real Bourne was a short 24-year old nicknamed the Kid (the real Bourne was offered a commission rather than a VC after the battle). Henry Hook, here a drunken malingerer with right-on 60s attitudes towards authority, was actually a teetotal model soldier (his granddaughter famously walked out of the premiere in disgust). Commissioner Dalton is a brave pen pusher, when in fact it was he who talked Chard and Bromhead out of retreating (reasoning the company wouldn’t stand a chance out in the open) and then fought on the front lines. Neither side took any prisoners – and the British ended the battle by killing all wounded Zulus left behind, an action that (while still shameful) is understandable when you remember the mutilation the Zulus carried out on the corpses of their enemies at Isandlwana the day before.

But it doesn’t really matter, because this isn’t history, and the basic story it tells is true to the heart of what happened at Rorke’s Drift. Brilliantly directed by Cy Enfield, it’s a tense and compelling against-the-odds battle, that never for a moment falls into the Western man vs Savages trope. Instead the Zulus and the soldiers form a sort of grudging respect for each other, and the Zulu army is depicted as not only disciplined, effective and brilliantly generalled but also principled and brave. The British soldiers in turn take no joy in being there (Hook in particular essentially asks “What have the Zulu’s ever done against me?”), admire as well as fear their rivals and, by the end, seem appalled by the slaughter. (Chard and Bromhead have a wonderful scene where they express their feelings of revulsion and disgust at the slaughter of battle.)

It’s a battle between two sides, where neither is portrayed as the baddie. We see more of it from the perspective of the defenders of the base, but the Zulu are as ingenious and clever an opponent as you are likely to see. The opening scenes at the court of Zulu king Cetshawayo’s (played by his actual great-grandson) allow us to see their rich culture and their own fierce traditions, grounded in honour (and spoken of admiringly by missionary Otto Witt, played with an increasingly pained then drunken desperation by Jack Hawkins, as he begs the British to flee and prevent bloodshed). Many of the Boer soldiers in the base compare the British soldier unfavourably with his Zulu counterpart. The film goes out of its way to present the Zulu people as a legitimate culture, and a respected one.

But its focus has to be on the British, as this is a “base under siege” movie, and to ratchet up the tension successfully it needs to chuck us into the base, playing the waiting game with the rest of the men. The Zulu army doesn’t arrive until over an hour into the film – the first half is given over entirely to the wait, the hurried preparations and the mounting fear as the seemingly impossible odds start to seep into the British. The men react in a range of ways, from fear, to anger, to resentment, to grim resignation. The first half also plays out the tensions between Chard and Bromhead, one a middle-class engineer, the other the entitled grandson of a General.

Caine is that entitled scion of the upper classes, and he plays it so successfully that it’s amazing to think it would only be a couple of years before he was playing Harry Palmer and Alfie. Caine nails Bromhead’s arrogance, but also the vulnerability and eventual warmth that hides underneath it. Set up as a pompous obstruction, he demonstrates his bravery, concern and even vulnerability. It’s a turn that turned Caine from a jobbing actor into a major star (Caine originally auditioned for Booth’s part as the working-class Hook. Booth later turned down Alfie). It also meant that Stanley Baker’s excellent turn, in the drier part as the cool, controlled Chard, buttoning down his fear to do what must be done, gets unfairly overlooked.

The film never lets up the slow build of tension – and then plays it off brilliantly as battle commences. Perhaps never on film have the shifts and tones of proper siege combat been shown so well. This is perhaps one of the greatest war films ever made, because it understands completely that war can highlight so many shades of human emotion. We see heroics, courage, self-sacrifice and unimaginable bravery from both sides. We also see fear, pain, horror and savagery from both. Several moments of bravery make you want to stand up and cheer or leave a lump in your throat (I’m a sucker for the moment Cpl Allen and Pvt Hitch leave their wounded bay to crawl round the camp passing out ammunition).

Enfield’s direction is masterful, the first half having so subtly (and brilliantly) established the relative locations and geography of everything at Rorke’s Drift, you never for one minute get confused about who is where once battle commences. The combat after that is simply extraordinary, a triumph not just of scale and filming but also character and storytelling. We are brought back time and time again to characters we have spent the first half of the film getting to know, and understand their stories. Eleven men won the Victoria Cross at Rorke’s Drift (more at one engagement than at any other time in history), and each of the winners is given a moment for their courage to be signposted. All of this compelling film-making is scored with deft brilliance by John Barry, with the sort of score that complements and heightens every emotional beat of the film.

Strangely some people remember this film as ending with each of the garrison being killed – I’ve seen several reviews talk of the men being “doomed”. Perhaps that impression lingers because there is no triumphalism at the end of the film. After the attack is repelled, with huge casualties, the soldiers don’t celebrate. They seem instead shocked and appalled, and simply grateful to be alive. After the final deadly ranked fire of the British, as the smoke clears to show the bodies of their attackers, the men seem as much stunned as they do happy. Bromhead talks of feeling ashamed, Chard calls it a “butcher’s yard”. Duty has been done – but the men were motivated by wanting to survive. The film doesn’t end with high fives and beers, but people quietly sitting, gazing into the near distance. There are small moments of dark humour from the survivors, but never cheers.

It’s all part of the rich tapestry of this enduring classic. Historically, many believe the celebration of the victory at Rorke’s Drift was to deliberately overshadow the catastrophe of Isandlwana (and that the number of VCs handed out was part of this). But, even if that was partly the case, it doesn’t change the extraordinary bravery and determination to survive from the soldiers. And the film doesn’t even try to get involved in the politics of the situation. The men must fight “because they are there” and the rights and wherefores of the war (which the film ignores completely) are neither here nor there. Instead this is a celebration of the martial human spirit, packed full of simply brilliant moments, wonderfully acted and directed, and an enduring classic. It allows you to root for the besieged but never looks down on or scorns the besiegers. It pulls off a difficult balance brilliantly – and is a brilliant film.