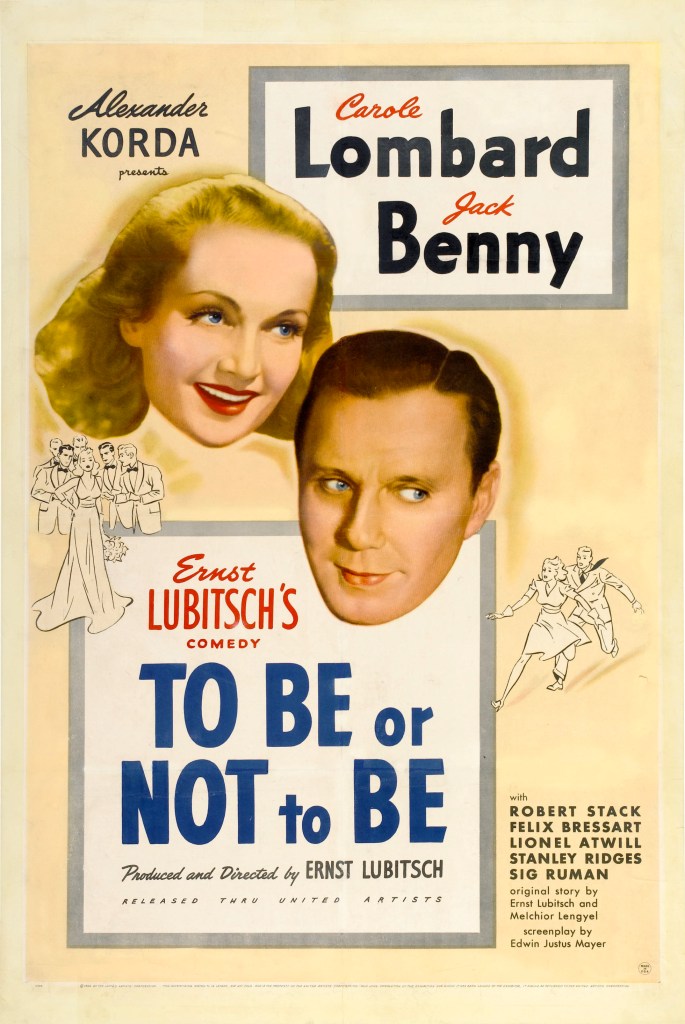

Hilarious Lubitsch comedy that walks a fine line between the dark horrors and absurdities of Fascism

Director: Ernst Lubitsch

Cast: Carole Lombard (Maria Tura), Jack Benny (Joseph Tura), Robert Stack (Lt Stanislav Sobinski), Felix Bressart (Greenberg), Lionel Atwill (Rawitch), Stanley Ridges (Professor Alexander Siletsky), Sig Rumann (Colonel Erhardt), Tom Dugan (Bronski), Charles Halton (Dobosh), George Lynn (Actor Schultz), Henry Victor (Captain Schultz)

Is there a setting less likely for the famous Lubitsch Touch than war-torn Warsaw? To Be or Not To Be is a farce set at the most serious of times, sharp-paced, smooth and very funny. But it’s also about how the sort of playful, civilised class of eccentric free-spirits that Lubitsch excelled at can win through, even at the most dreadful of times against barely-sane bullies. What To Be or Not To Be does best – as well as make you laugh – is give you hope there is some light at the end of the tunnel.

The Turas – husband and wife Joseph (Jack Benny) and Maria (Carole Lombard) – are the (self-proclaimed) most famous actors in Poland. But the season 1939 is tough: their latest play Gestapo (a piss-take of course) is canned because the government is worried it might upset Hitler. Joseph revives his Hamlet and Maria uses the start of his ‘To Be or Not To Be’ soliloquy as the perfect time to entertain her current lover Lt Sobinski (Robert Stack) in her dressing room. Flirtations like this get left behind after the Germans invade, Sobinski flees to join the RAF and the theatre is shuttered.

For most of that, To Be or Not To Be fits neatly into the Lubitsch Touch. The Tura’s – with their fast-talking wit and casual attitude to sexual fidelity – are not a million miles from Trouble in Paradise’s con artists. Joseph’s principal concern isn’t that his wife might be walking out with someone else, but that someone is walking out of his performance (the worst fate imaginable!). The company are a parade of theatrical hams (Lionel Atwill’s grandiose Rawich can never resist padding his role) or spear-carrying dreamers, like Felix Bressart’s Greenberg (dreaming of Shylock). These are all denizens of Lubitsch Land, and it’s all wonderfully funny, soaked in Lubitsch’s love for actors and theatre.

But the world they are about to step into is entirely different. Lubitsch opens the film with a hilarious misdirection: first it seems Hitler (Tom Dugan) himself is walking around Warsaw, before cutting to Jack Benny in Nazi uniform (a sight so shocking to Benny’s Jewish Polish Dad, he walked out and had to be coaxed by his son back in to finish watching it). But the conversation we hear – with its parade of nervous ‘Heil Hitlers’, ridiculous bribing of a small child with a toy tank – is slightly too absurd and, by the time Dugan’s Hitler enters with a proud ‘Heil myself!’ it becomes clear we’re watching rehearsals for Gestapo (at the end of which Dugan’s Bronski heads out into Warsaw to prove he can pass as Hitler).

It’s a fabulous lead into what we can expect for the rest of the film, which sees the actors swopping identities and character with desperate abandon as they get trapped into an espionage plot. In Britain Sobinski is rightly suspicious of Polish exile Professor Siletsky (Stanley Ridges), largely because he’s never heard of Maria Tura. With Siletsky carrying information to Warsaw that could shatter the resistance, Sobinski smuggles himself back into Poland and loops the actors –especially Joseph – into a complex, improvised deception scheme to get the deadly information back, save the resistance and dodge the real Gestapo under ruthless but desperate Colonel Erhadt (Sig Ruman).

To Be or Not To Be ups its gear into one of the wildest, riskiest and outrageous farces of all time. Jack Benny is front-and-centre as the vain-but-decent Tura, roped into impersonating first Erhardt to Siletsky, then Siletsky to Erhardt, with the help and hindrance of the company (many of whom, especially Rawitch, still instinctively take every chance to expand their roles). Benny’s comic timing throughout is exquisite, using every inch of his gift for comic vanity, brilliantly bouncing from assurance to barely concealed panic (usually when his pre-prepared lines run out). While working overtime to do the right thing, neither he – nor Carole Lombard’s beautifully performed Maria – step to far from the sort of flirtatious, catty banter that wouldn’t be amiss in a Noel Coward comedy.

Lubitsch’s film is in-love with actors, showing them as instinctively decent and brave, while also being squabbling, competitive misfits either pre-occupied with themselves (from Joseph unable to imagine anything worse than a bored audience, to a rehearsing Rawich not even noticing he has walked into a light backstage) or dreaming of glories to come. Sure, he has fun with their reliance on a script – Joseph runs out of lines so quickly as Erhadt he is hilariously reduced to simply saying over and over again “So they call me Concentration Camp Erhadt”, inevitable raising the suspicions of Siletsky – but at the same time in this crazy, dangerous world, the theatre is a bastion of civilisation.

Civilisation is of course in danger from the worst of the worst. Lubitsch is the comic director, par excellence but he is not afraid to dramatically shift tone and style throughout. The war action, as shells rain up towards Sobinski’s plane, would not look out of place in an action film. Sobinski’s attempt to contact the resistance could be dropped in from a Hitchcock thriller. When a Fritz Lang-inspired chase of Siletsky through a dark theatre is called for, Lubitsch goes entirely straight. The subtle threats behind Siletsky’s attempted seduction of Maria are quietly chilling if you stop to listen (Siletsky is the only character neither funny or on some level ridiculous, as if he has walked in from a serious thriller). There are moments in To Be or Not To Be that are surprisingly tense: when guns are pulled, we know having seen them used earlier that lives are at risk.

The most controversial element of To Be or Not To Be is whether Nazi occupied Poland is a suitable topic for comedy – and lines from Edwin Justus Mayer’s exceptional script like “What [Joseph] did to Shakespeare, we are now doing to Poland” feel close to the bone today. Lubitsch was of course not to know that plans were already being formed forthe Holocaust. But he had been the literal face of Hollywood Jewish corruption in the Nazi’s deplorable The Eternal Jew and the vileness of Nazism was familiar to him. He acknowledged it with Siletsky, the dogmatic, obsessed Nazi (who even dies with the word Heil on his lips). Erhardt brags about the powers of life and death he holds and casually talks of torture and executions. To Be or Not To Be couldn’t picture the evils of mechanised death, but Lubitsch knew the people he was dealing with.

He also knew nothing punctures evil like mockery – and, like most bullies, many Nazis were small, pathetic people. Erhadt – superbly played as a wide-eyed, panicked middle-manager and deadly dispenser of punishments by Sig Rumann – might be dangerous, but he’s also a twitchy, clueless idiot, blaming his subordinate for all his mistake (it’s part of the film’s joke that Joseph’s suave Erhardt feels more convincing than the bug-eyed ignoramus himself). The Nazis are small-minded bullies, with their continued parroting of Heil Hitler and kneejerk obedience to orders (up to jumping out of a plane). Lubitsch treats Nazism seriously while showing how ludicrously puffed-up and stupid it is.

It’s a fine tight rope walk, which echoesThe Great Dictator – but without Chaplin’s heartfelt, fourth-wall plea for peace and understanding. To Be or Not To Be manages to make identity switching farce a sort of commentary on how the Nazis are incapable of questioning the reality they are ordered to accept. Lubitsch shows Nazism as a cult diametrically opposite to the more libertine, bickering and free-minded actors. As such, it’s a valuable reminder in war time that we can prick the pomposity of tyrants by hitting them where it hurts them most: in their pride.