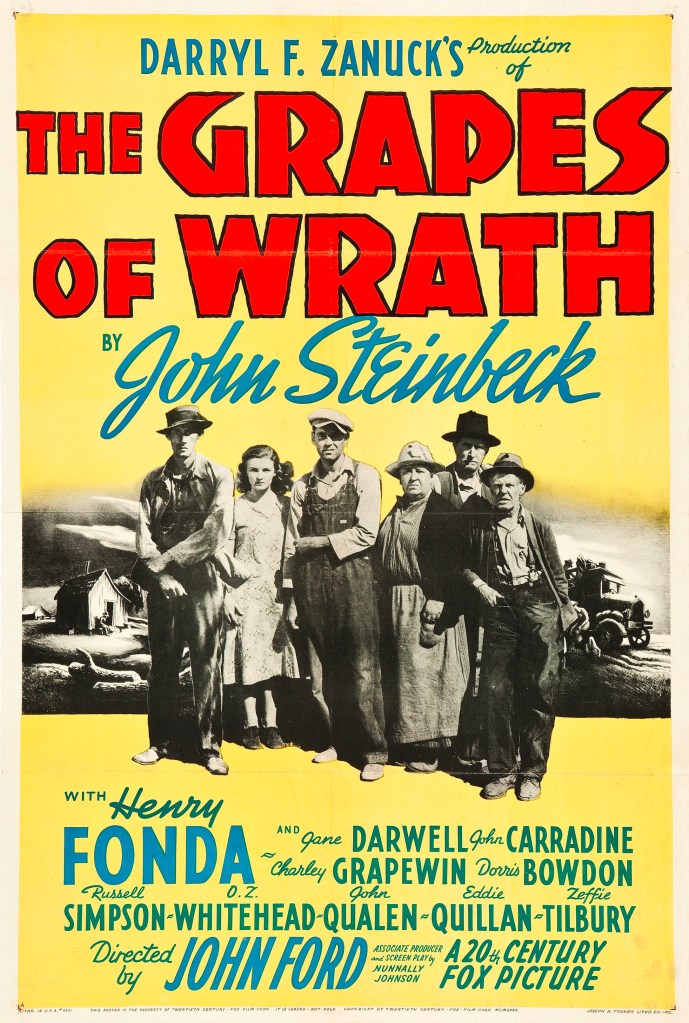

Steinbeck’s masterpiece is transformed into a richly humanitarian and heartfelt film

Director: John Ford

Cast: Henry Fonda (Tom Joad), Jane Darwell (Ma Joad), John Carradine (Jim Casy), Charley Grapewin (Grandpa Joad), Dorris Bowdon (“Rosasharn” Joad), Russell Simpson (Pa Joad), OZ Whitehead (Al Joad), John Qualen (Muley Graves), Eddie Quillan (Connie Rivers), Zeffie Tilbury (Grandma Joad), Frank Sully (Noah Joad), Frank Darien (Uncle John), Darryl Hickman (Winfield Joad)

If you can be certain of one thing, it’s that times of economic hardship rise and fall like waves on the shore. John Steinbeck’s novel The Grapes of Wrath was a searing, powerful exploration of the impact of the Dust Bowl, the Great Depression and new farming technologies on Oklahoma tenant farmers. It was almost immediately cemented as a Great American Novel. Just as Ford’s moody, heartfelt, humanitarian film of it was immediately hailed as a Great American Film.

In Oklahoma, Tom Joad (Henry Fonda) is released from prison (after killing a man in a bar fight) to find his farming community has been devastated. The Depression has shattered the market and the landowners now farm their land with tractors rather than people. Tom and his family have no choice but to load up a beaten-up van and migrate to California where they have hopes of work picking fruit for meagre wages. What they find on the way, among small acts of kindness, is exploitation, brutal policing determined to crush any protest from migrants and migrant camps in terrible conditions. Misery, death and the endless grind of fading hopes seems to be all they have to look forward to.

The Grapes of Wrath moved to the screen faster than almost any other novel in history. Published in April 1939, in months Nunnally Johnson had completed a script and shooting began in October for release in 1940. The unprecedented speed spoke to the book’s enormous impact, which has remained eternally relevant in its depiction of the hostility faced by migrants. Producer Darryl F Zanuck, despite his passion for the novel, worried it would be seen as pro-Communist propaganda – thankfully basic research showed Steinbeck had, if anything, played down the labour conditions. Zanuck was convinced he could defend any accusation of anti-Americanism – perhaps, as well, he decided recruiting the film poet of romantic Americana, John Ford, as director would lay any change The Grapes of Wrath could be seen as an attack on the US to rest.

Ford was in fact a near perfect choice as director. A man who held his Irish migrant roots close to his heart, he felt a powerful bond with these victims of changed circumstances. As a man with a romantic view of America’s Golden Age, he was equally critical of sharp technology changes (he shoots the tractors who plough through the Oklahoma farmland as monstrous tanks, crushing hope below their ominous caterpillar tracks). Working closely with cinematographer Gregg Toland, he shot a film with one foot in realism, the other in low-lit, moody impressionistic shadow, a rich visual treat that marries both methods to enforce the appalling economic situation it depicts.

From its opening shot, which frames Tom Joad walking across Oklahoma desert land framed with telegraph poles, the idea of ordinary people left behind by technological change rings out. Tom’s farmstead Tom is derelict with one tenant recounting his eviction in a cramped room lit by a single candle. The Joad’s leave for California in a truck so beat up, it only just starts and appears to be partially made of wood. The California shanty town they are herded into is contrasted with the sleek automobile of the landowner offering work for a pittance. In the government run camp, we see running taps and modern bathrooms that seem space-age compared to the squalor we’ve seen.

The Grapes of Wrath doesn’t shirk in its anger at the ill-treatment of these sons of the soil. In California, the bosses are cruel, uncaring and greedy. The flyers the Joad family clutch hoping for work, is one of thousands recruiting for only hundreds of jobs. Salaries are constantly undercut – at their second camp, the Joads work exhaustingly for just about enough to feed them for the day. The sheriffs are little more than heavies for the bosses, breaking up protests at pay, arresting and beating ‘trouble makers’ and turning a blind eye to any threats or danger to the migrants.

The injustice of it is captured in a superb speech by John Carradine’s Jim Casy, a former preacher whose faith has been replaced by a burning passion to protect the rights of the little guy. Shot by Toland in a shadow-drenched, candle-lit tent, Carradine delivers with impassioned brilliance an inarticulate but moving speech on the need for the workers to stick together to combat exploitation. He follows in the footsteps of an earlier ‘rabble rouser’, whose denunciation of a fat-cat businessman is met with gunfire from a sheriff (a woman being near-fatally shot in the aimless fire).

It’s feelings that will inspire Henry Fonda’s Tom Joad. Fonda is marvellous as this plain-speaking man with a streak of self-destruction, who learns to focus his anger aware from his own needs to fighting for others. With his father – well-played by Russell Simpson – increasingly ineffective, Tom transforms himself slowly into a leader. His lolloping stance doesn’t detract from his everyman nobility. Fonda even manages to make some heavy-handed, speechifying really work as a profound statement of human rights.

He’s joined in this with the film’s third stand-out, the Oscar-winning Jane Darwell as the indefatigable “Ma”. Darwell becomes the family lodestone and an epitome of resilient spirit, her pained but patient face returned to again and again. Darwell as at the heart of many of the most moving moments, perhaps the most one of its simplest: Ma quietly, with sad smiles, burning old mementoes and holding up a pair of earrings to study her reflection in the flickering candlelight. Ma holds the family together, from cradling the dying Grandma on the floor of the truck to desperately hiding Tom from the vindictiveness of the police. Ford closes the film with a powerful speech of hope and resilience from Ma, again wonderfully delivered by Darwell in simple, unflashy close-up.

Despite that delivery though, the end film’s final act doesn’t ring true with what has gone before. The film reshuffles the novel’s plot. That culminated in a bleak miscarriage in a windswept hut. The well-built government-run migrant town is a stopping off point, a moment of hope, in a grim journey towards desolation. Here it is the final destination – and the community dances, organised by benevolent caretakers, feels like a cheat of reality. Perhaps Zanuck felt a relatively hopeful ending was needed to balance those fears of Anti-Americanism. Either way, it never feels like a ‘real’ ending: this economic catastrophe didn’t end like this for many, so it shouldn’t for our everymen.

It is perhaps, though, the only major flaw in Ford’s superb film. It’s a film sprinkled with as many small moments of peace and hope as it is injustice. The Joads enjoying a swim in the lake, or the kindly garage staff who let Pa buy bread and sweets for the kids at a price far below their value warms the heart. The shanty towns are given a real sense of community by Ford. It makes the stark cruelty of those in charge stand-out all the more.

The film doesn’t shirk on the grim surroundings. The detail of the squalor is magnificently delivered, while the foreboding, shadow filled lighting of Toland’s photography is exceptional. With a host of excellent performances, Grapes of Wrath is the finest statement of Ford’s overlooked humanitarianism. He was a director with a warm regard for the common man, who believed in their righteousness and right to just treatment. This streak runs strong throughout The Grapes of Wrath and makes a film that is never sentimental, but arouses huge sentiment in anyone who watches it.