Iconic action adventure, a very exciting chase film with a strong script and characters

Director: John Ford

Cast: Claire Trevor (Dallas), John Wayne (The Ringo Kid), Andy Devine (Buck Rickabaugh), John Carradine (Hatfield), Thomas Mitchell (Dr Josiah Boone), Louise Platt (Lucy Mallory), George Bancroft (Sheriff Curly Wilcox), Donald Meek (Samuel Peacock), Berton Churchill (Gatewood), Tim Holt (Lt Blanchard), Tom Tyler (Luke Plummer), Chris-Pin Martin (Chris), Francis Ford (Billy Pickett)

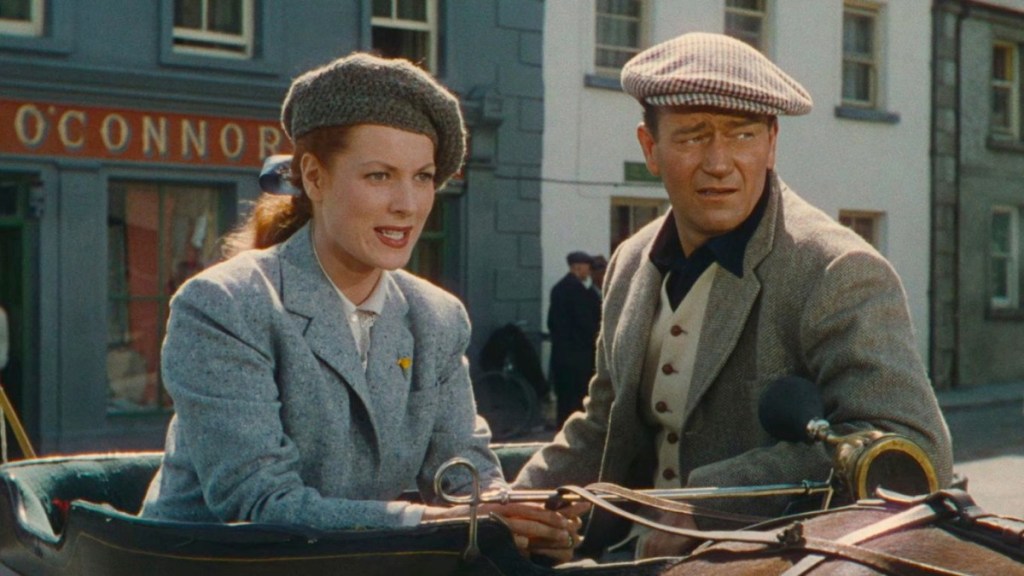

It might be the greatest star entrance of all time. Before Stagecoach, John Wayne was a minor leading man from a never-ending stream of oats-and-saddles B-movies. But, after one shot – a superb fast-paced zoom (so fast, the focus slips at one point) into the stoic face of Wayne, Winchester rifle twirling – that wasn’t going to be the case anymore. Stagecoach was Ford’s return to the Western – and he was bringing a friend along for the ride. After it, both director and star would become synonymous with the genre and Wayne would remain Hollywood’s Mayor-in-all-but-name.

Of course, that shot alone didn’t make Wayne a star (but, as you can imagine Andy Devine’s Buck wheezing “it sure helped, didn’t it”). What cemented the deal was what the hugely entertaining thrill ride Stagecoach is, a rollicking journey through Monument valley, crammed with just about anything you could want, from gun-battles and stunts to class commentary and arch dialogue. Like some sort of JB Priestley play, a regular smorgasbord of folks climb into a stagecoach to travel from Tonto to Lordsburg, facing a parade of dangers from Geronimo’s Apaches along the way – not to mention their own personality clashes and business to take care off in Lordsburg. All aboard!

We’ve got prostitute Dallas (Claire Trevor), run out of town by ‘blessed civilisation’ – much like drunken surgeon Dr Boone (Thomas Mitchell) – hoping for a new life. Army wife Lucy Mallory (Lucy Platt) trying to find her missing husband, escorted by Southern gent turned gambler Hatfield (John Carradine); both are more than a little uncomfortable sharing a carriage with a lady of the night. They probably wish the carriage had more people like bank manager Gatewood (Benton Churchill), although they might change their mind if they knew he was an embezzler. Sheriff Curly Wilcox (George Bancroft) is trying to catch escaped prisoner The Ringo Kid (John Wayne), who is himself keen to get to Lordsburg to take down the Plummer gang who killed his father and brother.

All of these well-drawn characters – including the timid whisky salesman (whose name no-one can remember) Peacock (well played by the suitably named Donald Meek) – are bought vividly to life by a strong bunch of actors working with a well-constructed script by Dandy Nichols, crammed with sharp lines and wit. It’s packaged together by Ford into a film that’s lean, plays out at a whipper-cracker pace and juggles several plots, threats and character motivations all at once.

You can see Ford’s mastery of story-telling throughout Stagecoach. The opening fifteen minutes is a superbly efficient piece of lean scene-setting which, in a series of tightly-focused, engaging scenes, brilliantly introduces the principle characters, their motivations and the twin dangers of the Indians on the road and the Plummers in Lordsburg all in perfectly digestible chunks. In addition, Ford carefully introduces the class commentary that greases Stagecoach’s wheels: from the unconcealed loathing and disdain Dallas is treated with by the town’s worthies (including the appalled revulsion of Hatfield and the marginally less strident disdain shown by Lucy) to the unquestioned bluster of blowhard fat-cat Gatewood, whose blatantly transparent lies and increasing nervousness draws no where near the level of suspicion it should do.

But then most people are too worried about catching sin-by-touch from Dallas. Stagecoach never outright states her profession, but only the naïve Ringo Kid seems unaware she’s on-the-game. At the first stop on the journey, Ford orchestrates a perfectly constructed scene of micro-aggressions and class structure, where Ringo guiltily utterly misreads as snobbery about his own jailbird past. (Hatfield is so committed to keeping the distance between himself and Dallas, he won’t even let her borrow his water glass as he does Lucy, tossing Dallas the canteen to drink straight from instead). Similar disdain also meets Dr Boone, whose utter refusal to even slightly moderate his drinking (he spends the first day getting sozzled) disgusts the elite passengers, right up until his skills are needed during a medical emergency. (At this point Hatfield starts treating him as the fount of wisdom).

Ford’s sympathies are, like so often, with the tough little-guys out in the West, who judge people by who they are and what they do rather than where they come from. Claire Trevor is perfectly cast as Dallas, never a victim but always full of patient defiance, all-to-used to the snubs from others. But we respect Dallas because it’s clear – from the start – she’s kind, considerate and decent. When the chips are down for Laura, it’s Dallas and Boone (not self-appointed guardian Hatfield) who step-up to save her, and never once does it cross their mind to hold Lucy to account first.

Just the same is, of course, The Ringo Kid. Stagecoach was possibly the last time Wayne could plausibly be called ‘the Kid’ – he looks older than his 32 years already – and he fills the part with a sincere honesty, courtesy and straight-forwardness that would become integral to Ford’s films, while still making the Kid the rough-and-tumble hero you want to be. The Ringo Kid may be a jailbird, but treats people according to their personal merits, sticks to his word, unhesitatingly protects people (that iconic introduction is him warning the coach of danger ahead) and won’t do anything he isn’t unwilling to do himself. It’s people like that – and Thomas Mitchell’s Oscar winning (Mitchell had key roles in half the best picture nominees that year, so had to win for something!) Doc Boone who turns himself into a master surgeon by force-of-will alone – who form the backbone of Ford’s West.

This all sits alongside some truly sensational action-adventure. Most of Stagecoach is a long build-up to its two action sequences that end the film: the running attack across the wide-open desert sands from the Apache and Ringo’s fateful duel with the Plummers. The eight-and-a-half minute chase would be the highlight of any film, a dynamic, pulsating masterclass of tight editing and tracking shots that fills the screen with electric pace and energy. It also has some of the most iconic stunts of all time, executed by Yakima Canutt Wayne’s long-term stunt consultant. From Canutt-as-Ringo jumping from pair-of-horses to pair-of-horses in front of the coach galloping at full-speed, to Canutt-as-Apache leaping from horse, to coach horses to falling and bring dragged under the coach (a stunt homage by Raiders of the Lost Ark’s truck chase) their visceral thrill is made even more exciting by Ford’s camera speeds making them look like they took place at even faster pace than the 45-miles-an-hour the horses were galloping at.

Ringo’s final duel with the Plummers gets a different approach, a long, steadily paced build-up that culminates in a very low camera watching a ready-for-action Wayne move towards us like a striding mountain. Stagecoach is also a masterclass in visual imagery and camera-use – so much so Orson Welles literally used it as such in prep for Citizen Kane, screening it over 40 times. Not just in action and editing, but also the brilliance of placement. Stagecoach’s low-ceilinged sets and striking shadows are a clear influence on Kane. A superb shot of Dallas from down a corridor, framed in light strewn from an open doorway, is a wonderful piece of visual poetry and there are gorgeous visual flourishes throughout, from the black cat that crosses the Plummer’s path to the wonderful vistas from Ford’s first trip to Monument valley.

All of this comes together into a film that is a wonderfully entertaining character study, wrapped up with a series of knock-out set-pieces, with romance, comedy and social commentary thrown in on top. It’s perhaps one of the most purely ‘entertaining’ Westerns ever made and one of Ford’s finest fusions of artistic brilliance and popcorn chewing thrill-rides.