Romance, make-overs and erotic cigarette lighting abounds in this classic luscious romance

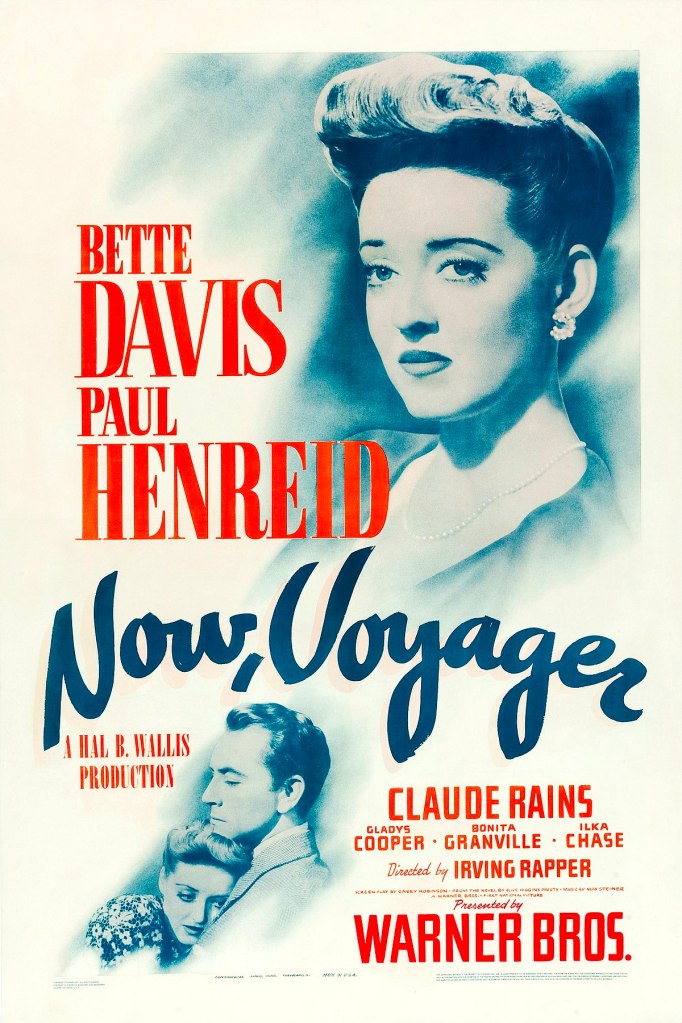

Director: Irving Rapper

Cast: Bette Davis (Charlotte Vale), Paul Henreid (Jerry Duvaux Durrance), Claude Rains (Dr Jaquith), Gladys Cooper (Mrs Windle Vale), Bonita Granville (June Vale), John Loder (Elliot Livingston), Ilka Chase (Lisa Vale), Lee Patrick (Deb McIntyre), Janis Wilson (Tina Durrance)

“The untold want by life and land ne’er granted, / Now, voyager, sail thou forth, to seek and find”. Walt Whitman’s words are the poetic urging of kindly psychiatrist Dr Jaquith (Claude Rains) to patient Charlotte Vale (Bette Davis) before she embarks on a cruise that will change her life. Crushed under her imperious mother’s (Gladys Cooper) thumb, Charlotte grew-up an unloved ugly-duckling and self-loathing spinster. How will a taste of freedom change her life – and, with that taste, a love affair with unhappily married would-be-architect Jerry Durrance (Paul Henreid)?

It’s easy to see Now, Voyager as a piece of soapy, romantic puff – and there are certainly suds in its DNA – but that’s to do an engaging, heartfelt character-study down. This is a sort of moral rags-to-riches story about a woman who has been mocked her whole life, finding the courage to build her own life. But that life is not the picture-perfect final image you might expect: instead, it’s about compromise and, more importantly, choosing your own compromises. Without knowing it, that is what Charlotte has been striving for. “Don’t let’s ask for the moon: we have the stars” are her famous closing lines, and it’s about the idea that choosing a compromised version of the life she actually wants is better than a life foisted upon her by others.

Now, Voyager works as well as it does, almost exclusively down to Bette Davis. She fought to get the role, hand-picked the director (an old friend) and stars (insisting on Henreid, despite a disastrous test) and reshaped most of the dialogue. It’s all justified by her superb performance. Charlotte Vale, with her ugly-duckling opening appearance, and operatic romance with Jerry, could have been a pantomimic performance. Davis though grounds her in sensitivity, reality and a deep emotional empathy. It’s a complex, heart-stirring performance.

Almost uniquely for stars at the time, Davis was not afraid to get ugly when the part demanded (she practically invented ugging-up). Charlotte Vale’s first appearance – Rapper teases the reveal by focusing first on her hands at her desk, legs as she descends a staircase before allowing her to fully enter frame – is a sight. With an eye-catching, hairy mono-brow, mousy glasses, a flattened haircut and dumpy clothing, she’s a million miles from our idea of 40s glamour. But Davis doesn’t make her a joke or play up to the appearance. She gives Charlotte a steel, born of self-defence – she snaps swiftly at Dr Jaquith when she thinks she is being condescended to – and a deep well of pain and ill-defined longing for a change she can hardly grasp.

Matters are beautifully inverted when she heads off on her cruise (you can criticise the film’s portrayal of therapy, which seems to be easy if you are stinking rich and can afford a cruise). Rapper repeats his intro trick again – this time revealing a physically confident and striking Charlotte, made-up and dressed to the nines. But, just as the self-loathing Charlotte had a defensive steel, so this ‘confident’ Charlotte has the same vulnerability and fear of ridicule and rejection just beneath the surface. Davis brilliantly gives the outwardly changed Charlotte, a different but equally moving vulnerability, a woman still working out who and what she is.

It’s a brilliant performance that gives the entire confection of the film a real emotional heft, as we experience every inch of this seminal voyage with her. And a lot of that life-change is filtered through the bond between her and fellow-passenger Jerry. Skilfully played by Henreid with a euro-charm that barely masks his own sadness, loneliness and guilt, Jerry may look the part but like Charlotte he’s close to succumbing to imposter syndrome. Unloved by his wife (this unseen harridan arguably deserves a film of her own – perfect role for Joan Crawford?) – but trapped into the marriage by his sense of duty and his love for his timid daughter Tina (Janis Wilson).

Jerry and Charlotte’s relationship blossoms from shyness into a genuine love affair. Reading between the lines of its 1940s code, it’s clear our two heroes get-it-on. Stranded in Brazil after a car crash (caused by an uncomfortably dated caricature portrayal of a Hispanic driver), the two of them ‘snuggle up’ for warmth while camping the night in an abandoned building. Any doubts about how far this went is removed when Henreid lights two cigarettes in his mouth in the next scene, passing one to Charlotte who sucks sensually on it. (This was the era when the language of cigarettes was crucial as a stand-in for bumping and grinding).

Of course, an affair could never be explicitly allowed, just as any idea of Henreid divorcing his awful wife was anathema. But its knowing that it-can-never-be which gives the film its romantic force. Charlotte will eventually find herself drawn to helping Jerry’s daughter Tina, their shared love for the child being the thing that will allow them to be married in spirit if not in actuality.

You could argue Charlotte’s decision to semi-adopt Tina as companion is not dissimilar from her own mother’s would-be exploiting of Charlotte as an unpaid nurse. But Charlotte has learned a lot from the cruel fierceness of her mother. Played with a witheringly cold grandeur by Gladys Cooper – at one point she taps her finger on a bed post in a way which captures oceans of barely repressed fury – this woman is selfish, self-obsessed and cruel. Standing up to her expectation that nothing has changed is the major challenge for Charlotte, with Bette Davis skilfully showing it takes all her strength to overcome.

Now, Voyager is an effective romantic film. It’s helped a great deal by Max Steiner’s beautifully romantic score, that perfectly complements and enhances every on-screen image. Superbly acted by its four leads – Claude Rains is also wonderful as the kindly and deeply professional Jaquith – it’s a detailed character study that manages to rise triumphantly above its soapy roots.