One of the best films about the magic and trauma of theatre, with two powerhouse lead performances

Director: Peter Yates

Cast: Albert Finney (Sir), Tom Courtenay (Norman), Edward Fox (Oxenby), Zena Walker (Her Ladyship), Eileen Atkins (Madge), Michael Gough (Frank Carrington), Lockwood West (Geoffrey Thornton), Cathryn Harrison (Irene), Betty Marsden (Violet Manning), Shelia Reid (Lydia Gibson), Donald Eccles (Godstone), Llewellyn Rees (Brown)

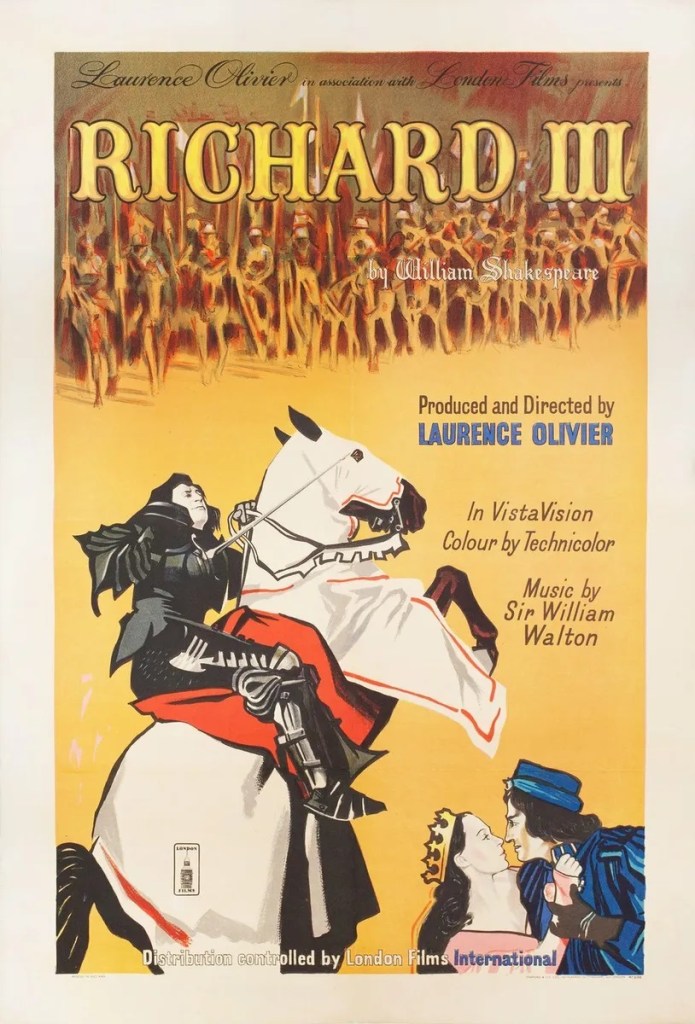

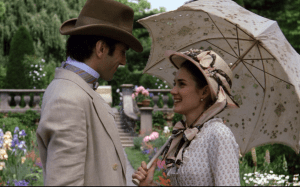

For centuries British theatre was run by Actor-Managers. Stars with complete control of their companies, where they (and their wives) played the best roles – sometimes years past the point where it was still suitable – until the next generation emerged to build their own companies. The Dresser shows this world’s dying days, at the height of the war, when Sir (Albert Finney) a legendary actor is shepherding an aged company around the provinces to perform, while his health and mental sharpness teeter, Lear-like, on the edge of the abyss.

If Sir is Lear, his Fool is Norman (Tom Courtenay) his dresser. A waspishly camp man whose entire life revolves around every inch of Sir’s whims, shepherding, coaxing and bullying the man onto the stage, somewhere between a valet, son and nursemaid. Sir remains a force-of-nature, toweringly bombastic egotist and man of magnetic charisma, with an all-consuming, obsessive love for the theatre. The Dresser takes place in January 1942 in Bradford, largely during a performance of King Lear which Sir’s declining health has placed on a knife-edge. Can Norman hold Sir together to give life to Shakespeare’s greatest tragedy for the 227th time?

The Dresser is based on Ronald Harwood’s play, which was semi-based on Harwood’s experiences as dresser then business manager to Donald Wolfit, one of the final breed of the old-school actor-managers Sir represents. (Harwood hastened to add, neither he nor Wolfit were portraits of Norman or Sir). While it’s a sometimes acidic look at the backstage politics and egos of touring theatre, it also richly celebrates the power of theatre and the momentary (and the film is unsentimental enough to show it is momentary) sense of family that can develop in theatre, that can end with that final curtain. In other words, The Dresser understands the brief, bright flame of theatre can be – and what a transformative feeling and dizzy drug it can be.

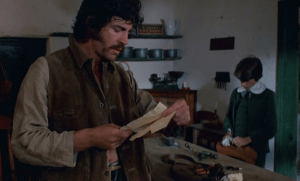

Both Sir and Norman are addicted to the grease-paint, their whole lives revolving around theatre and that elusive search for perfection. Even if Sir’s health is failing and sanity is crumbling – pre-show, Norman finds him raging in the streets of Bradford like Lear in the storm, only barely aware of who he is – ‘Dr Greasepaint’ can still briefly restore him to the man he was, spouting Shakespeare, bemoaning and relishing the huge weight of bringing art to life night-after-night. Norman is equally consumed by theatre: he can barely speak to others (such as train manager or a baker) without his conversation being littered with impenetrable theatre-speak. He’s as well-versed in Shakespeare as Sir is and flings himself into his backstage tasks with the same gusto Sir tackles a soliloquy.

These two have a symbiotic relationship: Sir for the support and dedication Norman exerts to get him on stage, Norman for the glorious world (and purpose) Sir gives him access to. Yates uses mirrors, framing and shared reflections to frequently frame these characters together, visually linking them in a Bergmanesque way as elements of the same personality. But, the relationship is never as straightforward as that, complicated by underlying feelings on both sides. Norman’s homosexuality – over-looked in a world where such feelings are a crime (another member of the company has recently been fired for what sounds like cottaging) – complicates his obsession with Sir, while Sir’s affection for Norman always has the hint of a Lord’s affection for his valet: a man he will confide in, but would never imagine inviting to dinner.

This complex interplay of both characters urgently needing the other, but with an underlying imbalance in their level of true emotional engagement is a subtle dance brilliantly handled throughout Yates’ and Harwood’s film: so much so, it is a surprise to many audiences that Sir utterly fails to mention Norman at all in his draft autobiography even though it’s about as likely as Churchill name-checking his butler in his. Sir and Norman may be partners in the same task – creating theatre – but Norman’s mistake is to see himself as an equal, something Sir never truly believes he is.

There is, however, no doubt about the partnership between the two actors. Tom Courtenay, who had played Norman on stage, is extraordinary. With his flamboyant hands and a voice divided between camp, whiny and ingratiating, constantly reaching for the bottle to power through the stress, Norman is as loyal, dutiful and comforting and he can be waspish, bitter, selfish, possessive and cruel. Courtenay can switch from coaxing Sir like a recalcitrant child, to throwing a potential rival for Sir’s attention to the wall and threatening all manner of damnation. It’s an astonishingly multi-layered performance, with Courtenay shrewd and brave enough to avoid making Norman a fully sympathetic figure but someone so soaking in desperation that even at his most self-pitying you feel for his desolation and emptiness.

Alongside him, Albert Finney is imperiously brilliant as Sir (playing a role almost 25 years older than him). Finney’s Sir is magnetic (they may grumble about him, but in person the company treat him with awe) and charismatic (his booming voice carries such power, it can even stop a departing train). But he’s also selfish, cruel, childish and intensely vulnerable. He’s got all the egotism of the actor (“The footlights are mine and mine alone. You must find what light you can.”), the productions revolve around him (he even continues to direct mid-performance, muttering instructions from Othello’s death bed). But he’s teetering, his mind crumbling, constantly looking to Norman for assurance, Finney living Sir’s fear at the approaching undiscovered country.

Both actors are extraordinary in a play that understands the addictive power of theatre. The Dresser avoids the trap of making Sir an Old Ham: in fact, the production we see (for all its old fashioned air) contains a performance of real power from Sir, rousing himself to touch something transcendent. Of all his 227 Lear’s this might be finest. Cynical technicians and wounded pilots weep openly. Thornton (Lockwood West), an ageing second-rate actor hastily promoted to Fool, talks of how the part has made him hungry for more. Oxenby (a marvellously louche Edward Fox), the youngest company member, clearly is ready for the new era (he carries a script full of bad language he longs to stage) but even he (after an initial point-blank refusal) throws himself into the backstage effort to create the storm. For all the rivalries, when the play is on, everyone briefly feels part of the same team working towards the same goal.

It’s a film with a melancholic feeling of an era coming to a close. It’s also one that punctures the character’s illusions. Sir is a star, but there are greater stars (with real knighthoods) in London; Norman may feel like his relationship with Sir is special, but Sir’s relationship with Madge (a brilliant Eileen Atkins, unflappably loyal and deeply pained under her professionalism) predates his and is more genuine. But it’s also one that understands the transformative power of live theatre. With stunning performances by Finney and Courtenay, backed by a marvellous, faultless cast it’s one of the finest films about theatre ever made.