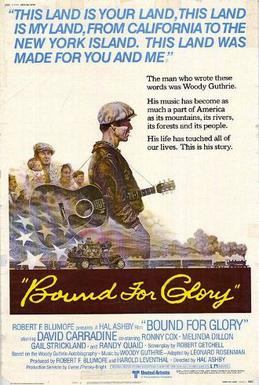

Beautifully filmed but psychologically and politically un-insightful film, easier to admire than enjoy

Director: Hal Ashby

Cast: David Carradine (Woody Guthrie), Ronny Cox (Ozark Bule), Melinda Dillon (Mary Jennings Guthrie), Gail Strickland (Pauline), Randy Quaid (Luther Johnson), John Lehine (Locke), Ji-Tu Cumbuka (Slim Snedeger), Elizabeth Macey (Liz Johnson), Mary Kay Place (Sue Ann), M. Emmet Walsh (Trailer Driver)

Woody Guthrie was a sort of poet of American folk music, his music influencing a generation of artists, from Bob Dylan onwards. His music spun a vision of the enduring strength of the working man and their rights to a share of the American Dream. It’s mythic stuff, so feels perfectly positioned to be spun into a modern fable in Ashby’s Bound for Glory. Coated in period detail, a sort of Grapes of Wrath by way of Barry Lyndon, it’s a lyrical piece of historical memory making with a nominal grounding in social and political issues. Is it a complete success? Perhaps it’s a film easier to admire than love.

It takes the title from Guthrie’s (David Carradine) biography, and follows his journey from Dust Bowl Texas in the 1930s to the hopes of employment in California, where he joins a mass of not-particularly-welcomed economic migrants. He discovers there an audience for his politically tinged folk music, but steadfastly refuses to compromise his principles. Actually, aside from these broad sketches and Guthrie himself, almost everything in this is essentially fictional. It’s a myth being spun, building a legend of a sort of John the Baptist of American folk music, a nostalgic vision of 30s America which makes little room for Guthrie’s actual politics.

Actually, that’s one of the most fascinating things in Bound for Glory. So keen is this to create a nostalgic view of an America from yesteryear, celebrating the perseverance of blue-collar America, it avoids talking in detail about anything Guthrie actually believed in. Although possibly not a card-carrying member of the Communist party, Guthrie was certainly at least a fellow-traveller. He had sharply left-wing, pro-worker, anti-capitalist views. His music echoed this – ‘This land is your land’ is actually about land ownership. But most traces of this have been carefully rinsed out of Bound for Glory.

That isn’t to say that it doesn’t take a deepe dive into Depression era America than any film since The Grapes of Wrath. Guthrie’s pilgrimage – and there is something distinctly Saintly about how he is presented here, making him more comfortable a figure than a left-wing radical – features plenty of dwelling on injustice and poverty. It opens in the ramshackle poverty of Dust Bowl Texas, where winning a dollar in a bet is potentially life changing. Migrants to California are at hurled from goods trains, then risk being shot (as one of Guthrie’s friends is) when attempting to jump on them as they puff past. They are barred entry on the road to California (in cars weighted down with their few possessions) if they can’t produce $50. The migrant camps are run-down, overcrowded and run by baton-wielding work-bosses who have complete power to decide who works and who doesn’t and don’t hesitate to wield their weapons to enforce their will.

Bound for Glory however avoids saying anything too firm against all this. It can carry sympathy for the plight faced by the working man but, much like The Grapes of Wrath, it’s terrified about saying or doing anything that could possibly be seen as promoting left-wing politics. Guthrie sometimes mumbles vague statements about the working man finding his slice of the American dream, but never anything too pointed about the fact that unfairness and having-and-have-noting is built into the system, like a spine in a body. The bravest shot the film takes is at a complacent priest, who smugly turns a hungry Guthrie away from his large church because he only hands out soup to people who have worked that day. Otherwise, the furthest it allows Guthrie to go is asking his wealthy lover (Gail Strickland in a thankless part) if she feels guilty having so much when others have so little. It’s the washed down, simplistic politics of the playschool.

And, to be honest, it robs Bound for Glory of much of its life and blood. It fails to replace this with a fierce personal story (like The Grapes of Wrath) and it never even attempts to make anything like a political statement as Ashby’s old collaborator Warren Beatty would do five years later with the similarly luminously beautiful Reds. Quite frankly, as Bound for Glory unrolls slowly and deliberately it does so with precious little fire and guts to it and (at times) very little interest. In other words, it’s very possible to sit and watch it and (while admiring it very much) kind of wish you were watching Rocky instead (as the voters for Best Picture at the Oscars that year clearly did).

It becomes instead a triumph of style, photography and design, rather than an enlightening biopic or making a statement about the Great Depression (other than it was tough). David Carradine hasn’t quite got the charisma to bring the vague threads Ashby gives him together. (Almost every single big name actor in Hollywood turned it down, which tells you something). Guthrie remains a vague, drifting blank, whose views and beliefs are undefined and to whom events frequently seem to just happen. Of the supporting roles (several women in particular get dull, thankless parts) only Ronny Cox gets something to get his teeth into as a musician turned union activist.

The real merits of Bound for Glory is it’s Barry Lyndon like recreation of a time and period. A lot of that is due to the breathtaking photography of Haskell Wexler – not for no reason was he the first person billed on the film. Wexler’s work is extraordinary, creating a sepia-toned view of Great Depression America that feels like its been taken straight from a photo library and placed on screen. Bound for Glory also astounded viewers at the time with the first Steadicam shot captured on screen, which starts with an aerial view, glides down to Guthrie and then follows him through a crowd of hundreds of extras to fail to be picked for a work party. It was the cherry on top of the Oscar-winning cake for Wexler.

It’s just a shame that these surface delights are all that really come to life. Other than that, this is distant, reserved and (in truth) slightly empty work from Ashby that presents the basic facts in a mythologised way that you feel removes much of the core truth. It turns a fascinating man of real conviction, into an unknown enigma, an Orpheus of the Dust Bowl who goes on a Pilgrim’s Progress that leads to (if we’re honest) nowhere in particular. It’s a film that strains a bit too hard for high art at the cost of passion or entertainment.