Very thin romantic drama that finds very little to offer beyond it’s set-up of “love across the divide”

Director: Henry King

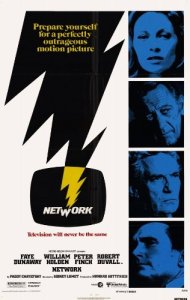

Cast: William Holden (Mark Elliott), Jennifer Jones (Dr Han Suyin), Torin Thatcher (Humphrey Palmer-Jones), Isobel Elsom (Adeline Palmer-Jones), Murray Matherson (Dr John Keith), Virginia Gregg (Anne Richards), Richard Loo (Robert Hung), Soo Yong (Nora Hung), Philip Ahn (Third Uncle)

In 1940s Hong Kong, Eurasian Dr Han Suyin (Jennifer Jones) works at a respected hospital and carefully balances her relationship with the Chinese and Western expat communities. All of which is shaken up when she falls in love with American journalist Mark Elliott (William Holden). As China’s civil war sees the country turn Communist – and with war rumblings in Korea – can this love across the divide survive prejudice, Mark’s estranged wife and the disapproval of her friends?

Love is a Many-Splendored Thing was a box-office hit and scooped no fewer than eight nominations (including Best Picture) in a weak year at the Oscars. It won two of them for its main virtues: the lush, romantic score from Alfred Newman and its title song (which became a massive hit). Aside from that, it’s a very slight romance (with a tragic ending) based on Han Suyin’s autobiographical novel (Suyin, who sold the rights because she needed the money, refused to watch it).

It’s very much a film of its time. The focus is at least as much on the locations and wide-screen framing as it is on story (it was made slap-bang in the middle of the era when these were considered cinema’s unique selling point over TV). Before the script was even completed, a second unit team was dispatched with the stars to shoot wordless sequences on location, all to capture that Hong Kong atmosphere. Writer John Patrick and director Henry King’s job was then to build a narrative framework using as many of these as possible, inspired by the book.

What they came up with is as conventional as they come: essentially, two charming, attractive Hollywood stars meet, flirt, fall in love and face the consequences. Despite the earth-shattering events around them, very little intrudes into the story. The outbreak of Chinese Communism gets name checked a few times – one of Suyin’s colleagues at the hospital is a proud Commie – but only a few moments are spent on considering the impact this might have on Hong Kong or the expat community. Similarly, the Korean War might as well have been started by people who just wanted to drag William Holden away from romantic bliss.

Love is a Many-Splendored Thing has its chances to really tackle the racial element of this relationship. But bar a few small moments, it mostly avoids this. Sure, Suyin loses her job for largely unspecified reasons (the implication is there that it’s for crossing this racial divide), and she gets dragged across town to get a ticking off from the grand doyen of the expat community for flirting with a white man (although this could just as well be for the fact he’s separated but still married). But her Chinese family mostly accept Suyin’s relationship with little complaint, and far more easily than they do her cousin’s relationship with a foreigner (guess it’s because Mark is such a top bloke). The whole issue feels slightly swept, awkwardly, under the carpet – which just doesn’t feel true. For all its patronising heavy-handedness, at least Sayonara two years later really engaged with this theme.

But then, maybe it’s because Jennifer Jones doesn’t even look remotely Asian. Reportedly unhappy with her make-up, its toned down to such a subtle extent that honestly half the time she doesn’t look that different than she does in any other role. I suppose, today, we should thank our lucky stars they didn’t go the whole yellow-face hog, but it does look odd considering everyone else of even remotely Asian descent is played by an Asian-American actor.

Despite this, Jones is actually rather good as Suyin: intelligent, sensible and very surprised to find herself falling in love with someone so socially unsuitable for her as Mark appears to be. She’s compassionate, witty and knows her own mind, and if Jones is given a few too many speeches explaining Asian culture to Mark (or rather to the viewer), at least she delivers them with grace and gravitas. Holden is also good, even if he could play this dashing romantic role standing on his head.

Fascinatingly both stars, despite their convincing on-screen chemistry, couldn’t stand each other. As well as having incompatible working styles – Jones was details oriented, Holden more instinctive – they failed to bond personally. (Jones reported she ate garlic to annoy famed lothario Holden, while Holden claimed a bunch of flowers he purchased Jones to clear the air were literally thrown back in his face.) It, surprisingly, doesn’t come across on screen, and the film’s strongest moments by far are the romantic ones between the two leads.

Fortunate, as that’s the meat of a film that barely has anything else on its bones during its swift runtime. King directs with a professional competent flatness that doesn’t give any additional life to the project. Aside from some decent romantic moments atop the couple’s favourite hill and a swimming sequence (obviously imitating From Here to Eternity but without an ounce of that film’s dynamism and sexiness) there is little to keep drawing you back.

Love is a Many-Splendored Thing settles for being a reassuring, lightweight romance, in which two handsome people, in luscious locations, fall in love. It offers very little outside of that, so basically your enjoyment of the film will be decided by how much that sort of thing wins you over. If you want more from your romances, it’s not for you.