|

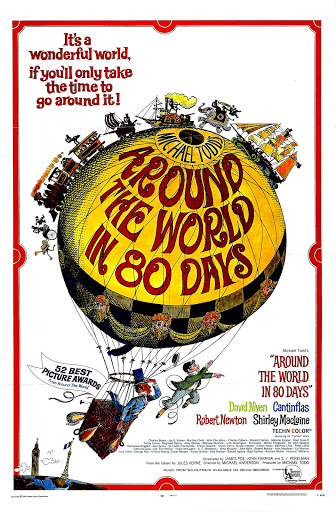

David Niven and Cantinflas head Around the World in Eight Days in this Oscar-winning epic |

Director: Michael Anderson

Cast: David Niven (Phileas Fogg), Cantinflas (Passepartout), Shirley MacLaine (Princess Aouda), Robert Newton (Inspector Fix), Charles Boyer (Monsieur Gasse), Joe E. Brown (Stationmaster), John Carradine (Colonel Proctor), Charles Coburn (Steamship clerk), Ronald Colman (Railway official), Melville Cooper (Mr Talley), Noel Coward (Roland Hesketh-Baggott), Finlay Currie (Andrew Stuart), Marlene Dietrich (Hostess), Fernandel (Paris coachman), Hermione Gingold (Sporting lady #1), Cedric Hardwicke (Sir Francis Cromarty), John Gielgud (Foster), Trevor Howard (Denis Fallentin), Glynis Johns (Sporting lady #2), Evelyn Keyes (Paris flirt), Buster Keaton (Train conductor), Beatrice Lille (Revivalist), Peter Lorre (Steward), Victor McLaglen (SS Henrietta helmsman), John Mills (London coachman), Robert Morley (Gauthier Ralph), Jack Oakie (SS Henrietta captain), George Raft (Bouncer), Frank Sinatra (Piano player), Red Skelton (Drunk), Harcourt Williams (Hinshaw)

In the 1950s, cinema struggled to encourage people to come out of their homes and leave that picture box in the corner behind. Big technicolour panoramas and famous faces was what the movies could offer that TV couldn’t. This led to a trend in filmmaking that perhaps culminated in 1956 with Around the World in Eighty Days triumphing among one of the weakest Best Picture slates ever seen at the Oscars. Around the World had everything cinema knew it could do well: big, screen-filling shots of exotic locations filmed in gorgeous colour; and in almost every frame some sort of famous name the audience could have fun spotting. It’s perhaps more of a coffee table book mixed with a red carpet rather than a narrative film: entertaining, but overlong.

Faithfully following Jules Verne’s original novel (with added balloon trips), Phileas Fogg (David Niven) is a punctilious and precise Englishman of the old school, whose life is run like clockwork and whose only passion is whist. Nevertheless he accepts a challenge from his fellow members of the Reform Club (among them Trevor Howard, Robert Morley and Finlay Currie) to circumnavigate the globe in 80 days or less. Setting off with his manservant – the recently hired, accident prone Passeportout (Cantinflas) – Fogg races around the world, from Paris to Cairo to India to Hong Kong to Japan to San Francisco. Along the way he rescues Princess Aouda (Shirley Maclaine) from death by human sacrifice in India and has to confront the suspicions of Inspector Fix (Robert Newton) who is convinced that Fogg is responsible for a huge theft at the Bank of England. Can Fogg make it back to the Reform Club hall on time to win his bet?

Around the World was the brain-child of its producer Michael Todd. A noted Broadway producer, Todd had been looking to make a similar splash in the movies. Perhaps it’s no surprise that he decided the finest way to do this (after the mixed success of a movie version of Oklahoma) was to produce something that‘s pretty much akin to a massive Broadway variety show. Around the World – as you would expect – is an incredibly episodic film, seemingly designed to be broken down into a number of small sequences either to showcase the scene’s guest star or to provide comic opportunities for Cantinflas to display his Chaplinesque physical comedy.

That and lots of opportunities for some lovely scenic photography. Nearly every major sequence is bridged with luscious photography capturing some exotic part of the world – from the coast of Asia to the Great American Plains. It’s pretty clear this is a major attraction of the film: come to the movies and see those parts of the world you’ve always dreamed of, just for the price of a movie ticket! Surely introduction of a hot air balloon to allow Fogg and Cantinflas to travel from Paris to Spain was purely to allow lovely aerial shots of the French countryside and chateaux. It’s the sort of film that proudly trumpeted in its publicity the number of locations (112 in 13 countries!), the vast number of extras (68,894!) and even the number of animals (15 elephants! 17 fighting bulls! 3,800 sheep!). It’s all about the scale.

That scale also carries across to the guest cameos. Between enjoying the scenic photography, viewers can have fun spotting cameos. Can that really be Noel Coward running that employment agency! The chap who owns the balloon, I’d swear that’s Charles Boyer! Wait that steward: that’s Peter Lorre! Good lord that’s Charles Coburn selling Fogg tickets for the steamer! Oh my, Buster Keaton is helping them to their seats on the train! Marlene Dietrich is running that saloon – and good grief that’s Frank Sinatra playing the piano! Most of the stars enter into the spirit of the thing, even if they frequently start their shots with backs to the camera, before turning to reveal their star-studded magnificence. Sadly time has faded some of the face recognition here, not helped by David Niven (perfectly cast as the urbane and profoundly English Fogg, so precise that his idea of romantic talk is to recount past games of whist) probably today being one of the most famous people in it.

Todd marshals all this with consummate showman skill. It’s handsome, very well mounted and generally entertaining – even if it is painfully long (it’s not quite told in real time, but can feel like it at points). The film is nominally directed by Michael Anderson. However, I think it’s pretty clear his job was effectively to point the camera at the things Michael Todd had lined up (be they location or stars) – Todd had already dismissed the original director, John Farrow, after a day’s shooting for not being sufficiently ”co-operative”. To be honest it’s fine as this is an entertainment bereft of personality, instead focused on being “more is more”.

Part of its extended runtime is due to the long comedic sequences given to Cantinflas. A charming performer – and possibly the most famous comedian in Latin-America at the time – Cantinflas can be seen doing everything from bicycle riding, to bull fighting (for a prolonged time), to gymnastics to horseback riding. (Far different from the unflappable and spotless English gentleman Niven is playing.) Your enjoyment of this may depend on how far your patience lasts. I’m not sure mine quite managed to last the course. Sadly one of Cantinflas’ greatest comedic weapons, his Spanish wordplay, was completely lost in translation.

There are some decent sections. The iconic balloon flight is well mounted and gives the most impressive images (the famously vertigo-suffering Niven was replaced by a double for much of this). Others, like the bullfight or an interminable parade in San Francisco go on forever. The casting of Shirley MacLaine as an Indian princess is an uncomfortable misstep (even at the time MacLaine felt she was painfully miscast), made worse by an offensive “human sacrifice” storyline – that got cut when the film was screened in India. Robert Newton though is very good value as the misguided but officious Inspector Fix.

Around the World in Eighty Days is grand, handsomely mounted entertainment. But to consider it as a Best Picture winner feels very strange. It’s not a lot more than an entertaining variety show, its plot impossibly slight (made to feel even more so by its vastly over-extended run time). While you can enjoy it in pieces, it finally goes on too long for its own good. Entertainingly slight as it is, it’s still one of the weakest Best Picture winners ever.