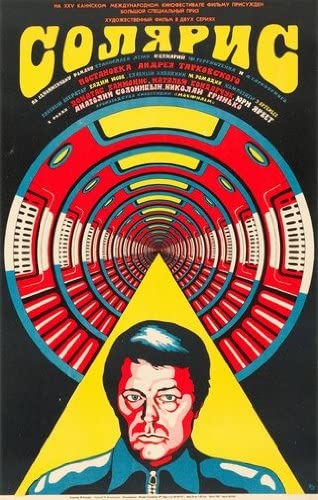

Tarkovsky’s search for inner meaning and depth in the framework of space

Director: Andrei Tarkovsky

Cast: Donatas Banionis (Kris Kelvin), Natalya Bondarchuk (Hari), Jüri Järvet (Dr. Snaut), Vladislav Dvorzhetsky (Henri Burton), Nikolai Grinko (Kelvin’s Father), Olga Barnet (Kelvin’s Mother), Anatoly Solonitsyn (Dr. Sartorius), Sos Sargsyan (Dr. Gibarian)

When Tarkovsky saw 2001 he was not impressed, calling it “a lifeless schema with only pretensions to truth”. Tarkovsky thought science fiction was in thrall to machinery and effects, rather than intellectual heft. (By the way, it shows how much Tarkovsky saw himself as a philosopher-poet, that he felt Kubrick a lightweight). Tarkovsky’s aim with Solaris was to present science fiction about people and ideas, rather than technology. Solaris is in equal parts fascinating and frustrating, wilfully slow (as Tarkovsky liked it) but also hypnotic, a film that never quite manages to marry up his stated aim to explore human feelings with his own intellectualist distance as a film-maker.

Adapted from Stanislas Lem’s novel, Solaris is set in an unspecified future and revolves around psychologist Kris Kelvin (Donatas Banionis). Kelvin is sent to a station orbiting the alien world of Solaris, an ocean world that quite possibly might be a gigantic living brain. It’s hard to tell if that’s the case, because contact with the planet has proved impossible over decades. Now the last three scientists on Solaris station are sending back strange reports and Kelvin’s job is to decide if the programme should continue. On the station he discovers the planet has somehow accessed the inhabitant’s dreams and made figures from their subconscious flesh – and he is horrified and then overwhelmed when his late wife Hari (Natalya Bondarchuk) appears on the station, a ghost made real by the strange powers of Solaris. How human is she? And does it matter?

Lem cordially disliked Tarkovsky’s Solaris. He couldn’t understand why the film didn’t exactly follow the book – where were the long chapters of scientific philosophical discussion? He felt it a shallow palimpsest of his work. I like to imagine that infuriated Tarkovsky, a director who prided himself on his intellectualism like few others. Huffily retorting films are different from novels, nevertheless he later claimed Solaris was the least favourite of his films, preferring the pretentious Stalker. But Solaris is ghostly and haunting in a way that the self-important Stalker (for me) never is.

Tarkovsky’s view of man’s exploration of the stars is that it blinds us to the more rewarding search for truth and meaning here on Earth. Not for nothing does the film start with a long, wordless, sequence following Kelvin walking through the grounds of his father’s dacha. Reeds dance in the river, long grass strokes Kelvin’s waist, rain spatters down from the sky. Nature is a key part of what makes us human – on the station, the scientists affix paper streamers to air vents to replicate the sound of wind among the trees, to make Solaris feel a little more like home. To Tarkvosky space is a boring, featureless mass, and Solaris nothing but a pale shadow of Earth’s glories.

What’s the point of hitting the stars, if we are cold and lifeless ourselves? Kelvin is this at the start of the film, a distant, emotionless man, plagued with regret, barely engaged emotionally with his world. A mysterious child runs around his father’s house – we assume it must be Kelvins daughter (Tarkovsky never confirms) but our hero never takes an interest in her. This will change with the appearance of Hari, exactly as he remembers her – unaged (she died at least twenty years ago) and a strange mix of who she was and his half-remembered memories.

But Kelvin isn’t ready to explore this yet. He puts the ghost in a rocket and shoots her off into space. Pointlessly, as his fellow inhabitants of the station tell him. They’ve tried similar with their own ‘visitors’ – they always reappear when they wake from sleep. And Kelvin can’t do the same again with the second Hari. Especially as this Hari is so distressed at the slightest separation from him, she tears her way through a metal door after he closes it on her.

It turns Solaris into Tarkovsky’s real aim: an exploration of what lies within, rather than ethereal dreams among the stars. As Dr Snout says, real exploration would require mankind to find a mirror not a rocket. Solaris becomes about how far Kelvin will go to emotionally connect to a woman who may or not be real and both is and isn’t the person he remembers. How much will he put aside his doubts and reconnect with feelings he has long suppressed? And in Hari’s case, as her self-awareness grows with every minute of her ‘existence’, how much will she change? And, as she is born from Kelvin’s guilt at her suicide, is she always destined to embrace self-destruction?

These ideas become the heart of Solaris, unfolding in Tarkovksy’s trademark style. Solaris is awash with long unsettling takes and an eerie lack of music – and even, in places, ambient sound – in which the actors move with a coldness and lackadaisical precision. Solaris is, in many ways, an awkward fit for the director. Tarkovsky is not one to embrace raw emotion. Donatas Banionis remains, throughout, an austere and unknowable figure, whose exact feelings remain at times unconnectable behind his stoicness. Solaris is like a terrible ghost story that looks at the impact of loss with the same professional interest Kelvin as a psychologist has. At times Tarkovksy seems like a philosopher juggling the enigma of humanity, but getting a little bored with the question. Crude as he would find it, an emotional outburst or two would do wonders for Solaris.

But perhaps that would sacrifice part of what makes Solaris as compelling, haunting and lingering as it can be. Because there is a feeling the whole thing is taking place in a drained-out dream that could cross into a nightmare. Hari is beautifully played by Natalya Bondarchuk, carefully balancing the slow flourishing of a shadow into a human, scared and alarmed by the onslaught of emotions she cannot understand. Her slow of a distinct personality, rather than as an extension of Kelvin, contrasts with the cagey uncertainty of the rest of the characters. And makes us wonder how real they might be, since she feels at times the most vibrant.

Tarkovsky’s film uses his style to wonderful effect throughout. His lack of interest in the trappings of the modern world actually adds to its eerie disconnect. Clothing and technology basically look exactly like the 1970s, cars are unchanged, the space station is a grimy wreck. Kelvin’s journey to the space station takes about 45 seconds of screen time – compare to the long, dreamlike drive Burton takes through the city (actually – and clearly – Tokyo). Tarkovsky’s heart is in the poetry of a horse’s movement. It adds to the sense of space exploration as a chimera and the 45 minutes the film takes in its prologue on Kelvin’s father’s dacha reminds us that understanding the world around and inside us is where Tarkovsky feels our aims should be directed.

Solaris ends with a sequence that has stayed with me for decades. Kelvin repeats his long walk through his father’s land, all of it this time in a chilling stillness. Not a gust of air or ripple on the water. He approaches his father’s house to see rain falling inside. A long cut back shows the truth. It’s a close to the theme Lem felt was least engaged with by Tarkovsky: the impossibility of communication between two species so fundamentally different they can only offer a simulacrum of each other’s behaviour.

Tarkovsky is straining for a different type of psychological journey. Solaris offers little in the way of emotional investment – it’s far too restrained, cold and distant for that. Such emotions are placed at the heart of Soderbergh’s remake – but that sacrificed the austere, ghostly haunting of this. Solaris plays like a construct from the planet of our emotions, thoughts and fears, its characters moving in journeys of discover in our world much as Hari does in theirs. It’s unknowability and discordant stillness and jagged long-shots make it unique. It’s one of the Tarkovsky films I always want to revisit.